Prairie grass ethanol will kill fewer people and foul the environment less than corn ethanol

Ethanol produced from switchgrass, prairie biomass, and Miscanthus will reduce the environmental and health impacts of expanded biofuels production relative to using corn as a feedstock, report researchers writing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Analyzing models developed by the US Department of Energy and the US Environmental Protection Agency, David Tilman and colleagues found that next-generation cellulosic biofuels produced from agricultural residues and grasses may improve air quality compared with corn-based ethanol production or continued burning of fossil fuels.

“Our work highlights the need to expand the biofuels debate beyond its current focus on climate change to include a wider range of effects such as their impacts on air quality,” said lead author Jason Hill, a resident fellow in the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment.

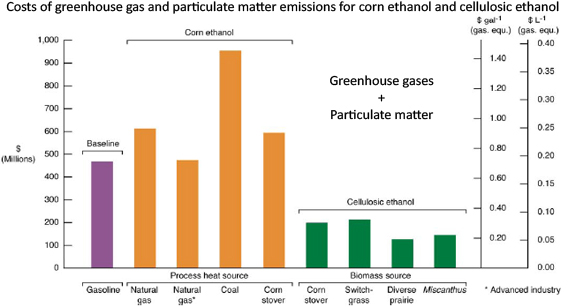

Courtesy of PNAS

The researchers simulated the impacts of a one-billion-gallon increase in U.S. production of the three fuels and found that the environmental and health costs of cellulosic ethanol are less than half the costs of gasoline and half to one-quarter the costs of corn-based ethanol.

“Total environmental and health costs of gasoline are about 71 cents per gallon, while an equivalent amount of corn-ethanol fuel costs from 72 cents to about $1.45, depending on the technology used to produce it,” explained a statement from the University of Minnesota. “An equivalent amount of cellulosic ethanol, however, costs from 19 cents to 32 cents, depending on the technology and type of cellulosic materials used.”

Switchgrass grown for biofuel production produced 540 percent more energy than needed to grow, harvest and process it into cellulosic ethanol, according to estimates from a large on-farm study by researchers at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The study involved switchgrass fields on farms in Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota. |

“These costs are not paid for by those who produce, sell and buy gasoline or ethanol. The public pays these costs,” added study co-author Stephen Polasky, an economist at the University of Minnesota.

The researchers looked at the full life-cycle emissions of fine particulate matter, an especially harmful component of air pollution, from production of the three fuels. They also evaluated the impacts of fertilizer and pesticide runoff into rivers and lakes. Increased use of nitrogen fertilizers for corn production has been linked to expansion of the dead zone — an area of low oxygen — in the Gulf of Mexico.

“To understand the environmental and health consequences of biofuels we must look well beyond the tailpipe to how and where biofuels are produced. Clearly, upstream emissions matter,” Hill said.

Jason Hill, Stephen Polasky, Erik Nelson, David Tilman, Hong Huo, Lindsay Ludwig, James Neumann, Haochi Zheng, and Diego Bonta. Climate change and health costs of air emissions from biofuels and gasoline. PNAS Online Early Edition the week of February 2-6, 2009

Related articles

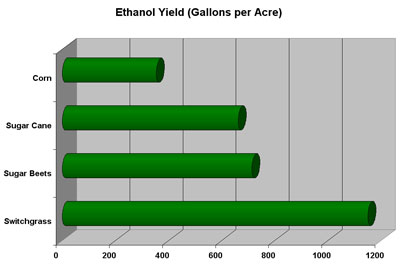

Ethanol yield for various crops

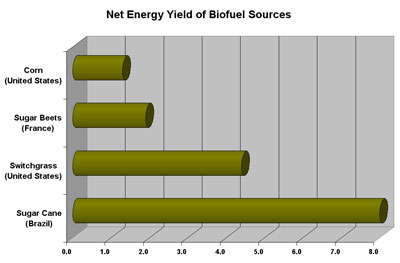

Net energy yield for various crops |

Switchgrass a better biofuel source than corn January 7, 2008

Switchgrass yields more than 540 percent more energy than the energy needed to produce and convert it to ethanol, making the grassy weed a far superior source for biofuels than corn ethanol, reports a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Ethanol may be greener but have higher health cost April 18, 2007

Widespread burning of ethanol as fuel may increase the number of respiratory-related deaths and hospitalizations relative to gasoline, according to a new study by Stanford University atmospheric scientist Mark Z. Jacobson. The report comes as mounting environmental concerns cloud the benefits of using ethanol as a “green” alternative to fossil fuels.

Corn ethanol is worsening the Gulf dead zone March 10, 2008

Proposed legislation that will expand corn-ethanol production in the United States will worsen the growing “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico and hurt marine fisheries, report researchers writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).