- Thousands who once lived near the Xingu River have been mostly relocated and compensated, but some refuse to go and have taken back territory by reoccupying the Belo Monte Dam reservoir.

- Overall, tens of thousands of people have been displaced by the dam, which was finished in 2015.

- Locals known as ‘river people’ are in the process of resettling the area near the reservoir, with over 100 people currently living there.

ALTAMIRA, Brazil – All is not quiet on Brazil’s western frontier. Families that were displaced from their homes on the Xingu River, which was blocked to make way for the controversial Belo Monte dam, are undertaking an audacious step to restore their way of life: They are reoccupying the riverbanks along the dam’s 200-square-mile reservoir. Belo Monte is the third largest hydroelectric project in the world.

As of February 2017, there were over 100 people occupying the reservoir. They have publicly declared that they are in the process of resettling the area.

The Xingu River is a 1,200-mile tributary of the Amazon River and is at the heart of the lives and homes of thousands of indigenous and various forest-dwelling communities.

The reoccupation action started after a November 2016 meeting when hundreds of locals assembled in the northern Amazonian city of Altamira (news is often slow to travel outside of Brazil). Altamira served as a staging area during the dam’s construction. At the meeting, local fisherman known as “river people” (ribeirinhos) and indigenous communities condemned Norte Energia, the consortium behind the multibillion-dollar dam project for what they claim is an unsuccessful compensation scheme and a failure to listen to their concerns.

Norte Energia has strenuously denied claims of a failed compensation scheme, as previously reported by Mongabay.

Crews finished construction of the dam and filled the reservoir in 2015, though turbines are still being built. In total, the Belo Monte complex has displaced about 20,000 people, according to estimates by global nonprofits such as International Rivers. The Brazilian advocacy group Xingu Vivo has put the number much higher, at over 50,000.

In the first two years of construction Altamira’s population surged to well over 100,000 and millions of dollars poured into the city, but the city now has seen a spike in joblessness and violence. A month after construction ended, 20,000 workers were laid off, and the economy in Altamira fell 52 percent, according to local reports on the news site Amazonia.

More than 800 people attended the November public assembly, organized by the public prosecutor’s office of Altamira, which addressed the social and environmental impacts of the 11,000-megawatt dam.

Representatives of Norte Energia and IBAMA were present. IBAMA is Brazil’s environmental authority and the licensing body of the project. It maintains a permanent channel of conversation with FUNAI (Brazil’s Indian Affairs Department) for any matters related to indigenous people.

There were also organizations supporting communities adversely affected by the dam. They included the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA), the local advocacy group Xingu Vivo, and the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science (SBPC), among others. The ISA is a Brazilian nonprofit civil society organization that works on socially responsible solutions to environmental challenges.

During the meeting, a group representing over 300 families of ribeirinhos (river people) displaced by Belo Monte announced that its members intended to resettle along the shores of the reservoir. They also announced the formation of a “river peoples’ committee” to fight against Norte Energia and lobby for adequate compensation.

“Norte Energia will try and divide us, but we must resist,” said Gilmar Gomes, a representative of the ribeirinhos’ committee.

Change in stature

Local ribeirinho families, some of which now occupy the Belo Monte reservoir, are known as “river people” because they live along the rivers and survive largely by fishing.

They have a shared history going back more than 100 years when the rubber boom opened up Brazil’s Amazonian interior to settlers that included their parents and grandparents. Over time, they have developed their own unique customs and means of living. Until recently, being called a ribeirinho was a pejorative term, and it was used as a slur.

Crucially, they are now recognized as a social group with a specific way of life. Before, they were simply seen as fishermen, explains Ana de Francisco, 34, an anthropologist contracted by ISA who researches ribeirinho communities.

“[Now] that is just an economic term,” de Francisco said. She explained that reducing them to mere “fishermen” is a way to deny their history. “It says nothing about their way of life,” she added. Now, ribeirinhos are working to reclaim the term, as well as the river, rebuilding homes along the shores of the reservoir.

Compensation claims and future plans

Thousands of families affected by the dam have been compensated and relocated. But many – including anthropologists, health experts and lawyers who have accompanied the process – argue that compensation was incomplete or non-existent.

There have also issues at the federal level with the basic functions of the project. Since 2014, Belo Monte has had its operating license suspended several times by Brazil’s environmental authority, IBAMA, for failing to comply with its agreed-to compensation scheme.

Norte Energia has been accused of using only 28 percent of the resources set aside to compensate those affected by the dam, according to the ISA.

In response to a request for comment on the ribeirinho committee and resettlement process Norte Energia said it remains in contact with community leaders.

“On a semi-annual basis, the company reports its activities in the socio-environmental area to IBAMA,” the company said in an emailed statement. However, Norte Energia did not comment specifically on the reoccupation or the ribeirinhos’ committee.

For the ribeirinhos, returning to their old way of life will present huge challenges; since the river was dammed, fish stocks have plummeted.

“This is going to take years, many years,” ISA’s de Francisco said. “It will take at least five years for the fish to come back … they are going back to a lake, to a totally new environment. So they will have to adapt. The question of how they will divide themselves on the land, how they will reconnect as neighbors and they will produce is a big question.”

Hydropower’s impact

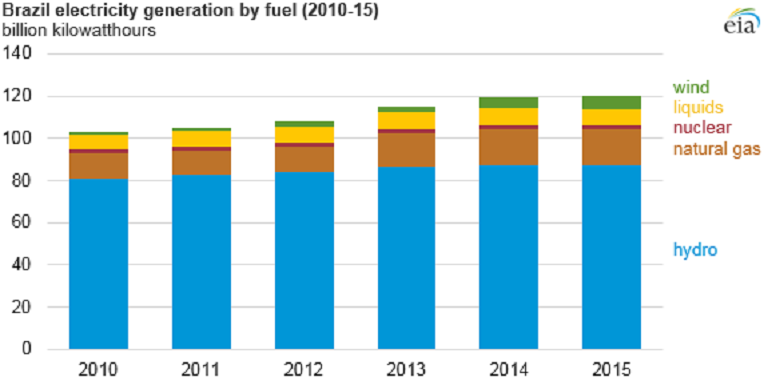

Hydropower makes up about 80 percent of Brazil’s energy production, according to the International Energy Agency. Though it is often touted as a green solution to energy concerns, the scientific community largely sees it as an environmentally and socially damaging way to generate energy. It can significantly impact natural habitats, land use and homes in the area of the dam. Though the number displaced by Belo Monte pales in comparison to the Three Gorges Dam in China, the world’s largest – which displaced over 1.2 million people – it has had a devastating impact on the local ecosystem of this remote jungle region and the people that depend on it.

The construction of the dam has also come at a time when changing weather patterns appear to be impinging on the livelihoods of people in the region. Ribeirinhos report hotter and drier seasons, which affect the river’s fish populations they rely on.

Recent scientific research on the Xingu River points to climate change as a possible cause. Brazil-based biologist Cristian Costa Carneira confirmed the changes in a recent interview. Carneira, who researches aquatic fauna, is part of an ongoing study under the auspices of the Federal University of Pará that measures the effects of manmade climate change on the Xingu River in Pará.

“We are seeing extremes in weather that are very abnormal,” said Carneira.

Separately, Norte Energia is in the first year of a required six-year study to measure the environmental and social impacts of Belo Monte and to determine if indigenous and fishing communities can continue to live downriver from the dam. There isn’t any published research yet because it is an ongoing study.

Lives forever changed

At the November ribeirinho meeting in Altamira, the scientific advocacy organization SBPC gave a 400-page report they produced on the dam’s social impact to the public prosecutor. Though the report is not available online, Mongabay has obtained a copy. Based on three months of field research, it claims that Norte Energia has effectively ended the ribeirinhos’ way of life and means of subsistence.

The report states: “With the forced displacement of the ribeirinho communities, they lost their territory, access to the natural environment and resources that they relied on for their livelihood and income, which means that they were robbed of the conditions that guaranteed their social and cultural reproduction … When they were displaced they began to buy practically all foodstuffs, living in a situation (of) food insecurity.”

The report also points out that the ribeirinhos were dealt a first blow when their homes were destroyed and then a second one with the chaotic implementation of its compensation scheme. The report called on the company to immediately change its course and implement a compensation scheme that follows the report’s guidelines.

A major issue stressed in the guidelines for the company to respect is the International Labour Organisation’s convention of “self-recognition” of traditional peoples, of which Brazil is a signatory.

Norte Energia was accused of using a “divide and conquer” strategy to move them out of their homes before they were flooded. They were dealt with individually and given “all or nothing” ultimatums before being resettled to neighborhoods on the outskirts of Altamira or onto inadequate alternative land, according to the study. Others were moved onto their neighbors’ land, or next to mega-ranches, which could sow conflict in a region that is already beset with land-related violence and land theft. Land rights in Brazil’s interior have often been acquired through “grilhagem” – the falsification of land titles.

Meanwhile others that were displaced did not have the necessary documentation to receive any compensation at all.

The report also called on the company to provide the financial means for them to rebuild their homes in order to return to their way of life, while assuring they have access to essential public services.

“This council should have been formed years ago, even before Belo Monte was built,” said Thais Santi of the public prosecutor’s office in Altamira, who is providing legal assistance for the case. One of the first steps necessary to move things forward, Santi explained, is for IBAMA to recognize the council.

Banner image: The Belo Monte megadam, Pará state, northwestern Brazil. The dam cut off the Xingu River and reduced its flow by 80 per cent, December 2016. Photo by Maximo Anderson for Mongabay

Maximo Anderson is a freelance journalist and photographer currently based in Colombia. You can find him on Twitter at @MaximoLamar

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Background:

Fearnside, Philip M. (2017). Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam: Lessons of an Amazonian resource struggle. Die Erde. Geographical Society of Berlin.

International Energy Outlook 2016. U.S. Energy Information Administration.

End of Belo Monte works highlights unemployment in southwestern Pará, Amazonia, June 30, 2016

Belo Monte becomes reality, but chaos in the city of the plant is forever, Folha de S.Paulo, March 20, 2016

Juruna block Transamazon to collect projects for Belo Monte, Amazonia, June 30, 2016

Documentary shows impacts of Belo Monte Hydroelectric plant for local population, Agência Brasil, October 10, 2016

Murder of Brazil official marks new low in war on Amazon environmentalists, The Guardian, October 24, 2016