Mayan women protest hydroelectric dam projects in Santa Cruz Barillas in western Guatemala on March 16, 2014. Local opposition to the construction of dams and other natural resource projects in the area has resulted in a government crackdown on activists. Photo credit: Luis Miranda Brugos / Alba Sud Fotografia.

Mayan women protest hydroelectric dam projects in Santa Cruz Barillas in western Guatemala on March 16, 2014. Local opposition to the construction of dams and other natural resource projects in the area has resulted in a government crackdown on activists. Photo credit: Luis Miranda Brugos / Alba Sud Fotografia.

Thursdays are one of two visiting days at the men’s pre-trial detention center in the city of Huehuetenango. Women from around the department (also called Huehuetenango) in western Guatemala begin lining up outside early in the morning, and at nine, they filter in to see their relatives. Detainees and visitors congregate in small groups, sitting on plastic stools in one of the two open cement spaces in the overcrowded facility, located just a few blocks from the city’s central plaza.

Saúl Méndez and Rogelio Velásquez don’t have any other visitors today besides this reporter. They are a gruelling eight-hour bus journey south of their home in the municipality of Santa Cruz Barillas, and their partners are each caring for several young children while trying to make ends meet. It’s not the first time the two community leaders have been deprived of their freedom for their role in grassroots opposition to transnational companies’ hydroelectric dam projects—including at least one project "green-stamped" to sell carbon credits to international investors.

“Our community has been at the forefront of this struggle,” Méndez says, leaning forward a little to be heard over the din of conversation.

Saúl Méndez (left) and Rogelio Velásquez, pictured above in court after an appeal hearing on April 29, 2015, have spent most of the past three years in pretrial detention on various charges. They are both community leaders who oppose hydroelectric dams in Santa Cruz Barillas, Guatemala. Photo credit: Gustavo Illescas / Centro de Medios Independientes.

Bordering Mexico and traversed by the highest mountain range in Central America, the department of Huehuetenango is one of the country’s most diverse departments, home to nine different Mayan peoples. Within the past decade the national government has granted concessions to several companies for hydroelectric dams in northern Huehuetenango without consulting the local Mayan population or obtaining their consent, activists charge. According to government data, as of 2012, licenses for eight hydroelectric projects in the department had been approved or were being processed.

Communities engaged in fierce resistance to the dam projects have been experiencing a multi-pronged crackdown by the government. In addition to Méndez and Velásquez, four other men from Santa Cruz Barillas and two indigenous Maya Q’anjob’al leaders from the neighboring municipality of Santa Eulalia are locked up, apparently for their roles in opposing the projects, too. There are outstanding arrest warrants for at least ten other women and men, all of them involved in community-based opposition to hydroelectric projects.

Moreover, three activists have been murdered — two of their bodies showing signs of torture.

“We’ve been confronting a pretty big monster,” says Velásquez. Poor people have always been marginalized and indigenous rights have never been respected in Guatemala, he says. “We hope to be out one day and enjoy our freedom.”

The most contentious of the hydroelectric projects is a proposed dam on the Canbalam River in Santa Cruz Barillas that Hidro Santa Cruz, a subsidiary of the Spanish energy company Hidralia Energía, has been attempting to get off the ground. The company has reportedly received financing for the project from the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank. The Canbalam I hydroelectric project is also certified by the UN to sell carbon credits under the Clean Development Mechanism.

Originally from another part of the department of Huehuetenango, Rubén Herrera arrived in Santa Cruz Barillas with a wave of returning refugees and people who had been internally displaced during Guatemala’s 36-year armed conflict, which ended in 1996. He worked on youth empowerment, leadership training, and other initiatives for 17 years and has been active in local, regional, and national movements to protect lands from mining, hydroelectric dams, and other natural resource projects. He is currently the sub-coordinator of the Departmental Assembly of Huehuetenango in Defence of Territory (ADH), a coalition of indigenous and grassroots community groups.

When energy companies started arriving in Santa Cruz Barillas with plans for hydroelectric dams in 2008, they were met with local resistance right off the bat, Herrera told mongabay.com in an interview at a research center in Huehuetenango.

“When [Hidralia Energía subsidiary Hidro Santa Cruz] tried to win people over, there was already fairly significant opposition to the project,” Herrera said. The previous year, in 2007, more than 46,000 Santa Cruz Barillas residents voted against mining and natural resource exploitation in a community-driven consultation process. As in more than two dozen municipalities in the department of Huehuetenango alone, local residents pushed their municipal governments to hold the consultations in order to make their voices heard. Out of a total population of roughly 125,000 residents, only nine people in Santa Cruz Barillas voted in favor of mining.

“That consultation united and raised awareness among the majority of the people in Barillas,” Herrera said.

The movement against Hidralia Energía and other companies intent on building dams on rivers in northern Huehuetenango grew quickly, with Q’anjob’al, Akateco, Chuj, Popti, and non-indigenous people in the region forming a united front. The Guatemalan government continued to support and grant licenses to hydroelectric projects despite the clear, overwhelming local opposition. As a result, during the five years following the energy companies’ arrival in the area, communities resorted to direct action.

Santa Cruz Barillas, Guatemala. Photo credit: Luis Alejandro Jm.

Local residents showed up to prevent company employees from carrying out their surveying work on the rivers, effectively detaining them. On one such occasion, Herrera was called in to help mediate and ensure the safe release of the employees, but was later charged with kidnapping. Tensions ran high, but no employees were harmed. In 2011, communities effectively kicked the company out of the region. There is no longer any active work on the hydroelectric project; however, Hidralia Energía has not given up and its subsidiary maintains a minimal presence in Santa Cruz Barillas.

“A campaign of accusations and smears against all of us began,” said Herrera. The wave of criminal charges against community leaders began in late 2009, but really took off in 2011, he said. Herrera has first-hand experience in the matter. He faced charges, was detained and acquitted, but eventually left Santa Cruz Barillas due to threats and judicial persecution.

In several different cases, charges were laid against dozens of local community leaders and movement participants for everything from illicit association to terrorism. Herrera, Méndez, Velásquez and others spent months in detention. Legal proceedings are ongoing in the various cases of the eight community leaders now behind bars as well as others who are not currently in detention. To date, however, all of the cases against people opposing hydroelectric projects in northern Huehuetenango that have concluded have ended in acquittals due to lack of evidence. All except for one case — that of Méndez and Velásquez.

On August 27, 2013, Méndez and Velásquez went to court for a final hearing to conclude legal proceedings against them. They had been free since January of that year, after eight months in detention. When they showed up outside the courthouse, however, they were both detained. To everyone’s surprise, they were accused of being accomplices in a double homicide that was entirely unrelated to the movement against hydroelectric dams.

In August 2010, residents of a community in Santa Cruz Barillas detained Mateo Diego Simón, a man known in the area for years as a member of a group of thieves working together to rob local residents. Residents handed the man over to the police, but after getting word that he was to be released the following day, the situation spiralled out of control. By the end of the day, a mob of some 500 people tied up and strangled Diego Simón and Guadalupe Francisco Felipe, the woman identified as the thieves’ ringleader, to death.

Méndez and Velásquez maintain they had nothing whatsoever to do with the August 2010 lynching, which did not take place in their immediate community. Years after the fact, however, the two community leaders were detained on the day another case against them was to be closed. Out of the estimated 500 people involved, witnesses claim to have recognized only two people: Méndez and Velásquez. Linking the two men to the 2010 double homicide was an elaborate set-up, said Herrera.

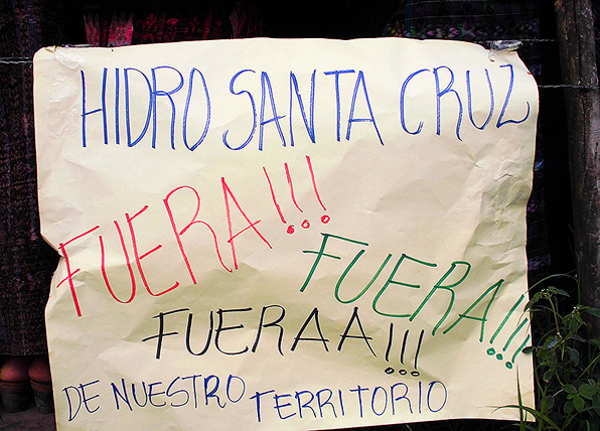

A sign at a protest against hydroelectric dams in Santa Cruz Barillas on March 15, 2014. The sign refers to the company responsible for a contentious dam that has been linked to murders and detentions of local activists, saying "Hidro Santa Cruz Out!!! Out!!! Out!!! of our territory" Photo credit: Luis Miranda Brugos / Alba Sud Fotografia.

“That’s the real context of Saúl and Rogelio’s situation: a tumultuous incident in which more than 500 people participate. Only they are identified, only they are accused, and only they are tried and initially convicted,” said Herrera.

In November 2014, the two men were sentenced to 33 years in prison. On May 15, 2015, a Huehuetenango court declined to ratify the conviction or sentence and ordered a retrial. The men remain imprisoned in Huehuetenango’s detention center awaiting their retrial.

Méndez and Velásquez are not the only Santa Cruz Barillas community leaders to be arrested upon showing up at an unrelated court hearing. On June 2, 2015, Bernando Ermitaño López Reyes was detained in Guatemala City when he attended a hearing to show his support for three other men from Santa Cruz Barillas in their ongoing trial. López Reyes was one of the nine men and four women for whom arrest warrants were ordered on April 3, 2015. A well-known community leader and a candidate currently running for mayor of Santa Cruz Barillas, he is charged with kidnapping and incitement.

Sergio Beltetón, a lawyer who has worked with the Campesino Unity Committee land-rights organization for years, has seen the same pattern crop up in conflicts over land, mines, dams, and other projects time after time.

“The government never consults the people, and because of that, unrest emerges. When people oppose hydroelectric dams, conflicts come about that sometimes result in violence,” Beltetón told mongabay.com. “What the companies do is take advantage of the situation to criminalize leaders, in an attempt to bring down the movement. So that’s the chain reaction: no consultation, social protest, and the criminalization of social protest.”

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) raised similar points in its concluding observations of its periodic review of Guatemala, released in Spanish on May 15, 2015.

“The committee is concerned about the high level of unrest that arises from the granting of licenses or permits for hydro-electric, natural resource exploitation, or monoculture plantation projects in lands and territories that belong to indigenous peoples or that have been traditionally occupied by them. The Committee notes with concern that these concessions have been granted without respect for the right of indigenous peoples to consultation,” CERD noted in its observations.

The Committee also addressed the criminal charges that often stem from protests and conflicts related to natural resources. “The Committee notes than in many cases, attacks and homicides occurred in the context of conflicts linked to the exploitation of natural resources. It concerns the Committee that these protests often originate criminal proceedings against activists, using charges such as terrorism, kidnapping, incitement to commit a crime and illicit association, which end up being disproportionate to the gravity of the incidents,” the UN body wrote.

The movement against hydroelectric projects in northern Huehuetenango has had to confront other challenges in addition to the wave of criminal charges. People active in the movement have been murdered, as has happened elsewhere in Guatemala. Earlier this year, on March 27, 2015, the body of Santa Cruz Barillas community leader Pascual Pablo Francisco was found with signs of torture four days after his abduction. On April 7, 2013, local Q’anjob’al leader and ADH member Daniel Pedro Mateo was abducted in Santa Eulalia. His body was found with signs of torture nine days later. No one has been charged for the murders; however, Herrera, Méndez, Velásquez, and many others believe the company is behind the crimes.

A banner memorializing Daniel Pedro Mateo is displayed at a protest in the central park of Santa Cruz Barillas on March 14, 2014. Mateo, an indigenous leader who opposed local dam projects, was abducted and killed nearly a year earlier, and his body was found with signs of torture. The banner refers to him as a martyr and hero for the defense of collective rights, the territory, and Mother Nature, and quotes him saying "If they kill me, let it be for a just cause." Photo credit: Luis Miranda Brugo / Alba Sud Fotografia.

Another murder set off a chain of events back in 2012. On May 1, Andrés Pedro Miguel was shot and killed, and Pablo Antonio Pablo and Esteban Bernabé were shot and wounded while walking home from the local fair in Santa Cruz Barillas. The alleged shooter was a security guard for Hidro Santa Cruz, though he and another company guard were both found not guilty the following year. All three victims of the attack opposed Hidralia Energía’s plans for the hydroelectric dam on the Canbalam River, and Pablo in particular is an outspoken Q’anjob’al community leader in the movement against the dam who had refused to sell land to the company.

News of the attack traveled quickly, sparking massive unrest. A hotel where dam company employees were reportedly staying was ransacked, and people took over the local state security forces installations. The Guatemalan government declared a state of siege in Santa Cruz Barillas that same day, on May 1, sending in hundreds of soldiers and police officers. Key constitutional freedoms and rights were suspended, including the freedoms of movement and assembly and the rights of detainees and prisoners.

For many adults in northern Huehuetenango, the state of siege brought back horrific memories of the country’s 36-year internal armed conflict. A UN truth commission concluded that state security forces carried out acts of genocide against civilian Mayan populations in several regions around the country. Between 1960 and 1996, more than 200,000 people were killed, tens of thousands were disappeared, and an estimated 1 million people were displaced. Like much of the highlands region where the majority of the population is Mayan, Huehuetenango was hard hit during the conflict.

At the detention center, Méndez and Velásquez explain how the events of 2012 brought Santa Cruz Barillas residents back to the worst of the war. “The state of siege wasn’t a state of siege; for us it was a reminder of 1981,” says Velásquez.

Many residents experienced terror at the massive influx of state security forces in May 2012. Méndez’s father, for example, fled into the mountains during the state of siege. Méndez himself was a child during the worst of the conflict in the early 1980s, but he remembers the fear his family experienced when his uncle was forcibly disappeared and presumably executed.

“It’s something that’s quite painful,” Méndez says of the militarization during the recent state of siege. “They arrived to threaten people. They told the people to tell them who the leaders were.”

On May 2, Méndez and Velásquez were detained for the first time. They were two of 12 community leaders arrested in the days immediately following the declaration of the state of siege, which lasted 17 days.

Méndez and Velásquez have been in and out of detention on a variety of charges ever since: over the past three years, they have spent all but seven and a half months behind bars. Now they’re just anxious for news of when their retrial will begin.

“Waiting for a date is tormenting us a little,” says Velásquez. “We want the trial to happen soon and for the truth to be clarified.”

A loud noise suddenly resonates throughout the detention center. It’s the first of several, letting people know that the two-hour visiting period is coming to an end. It’s time for the more than 200 detainees to return to their five overcrowded cells for a headcount before the visitors file back out.

These last nine months in prison have been hard on Méndez and Velásquez. However, so many people and organizations are supporting them, and the communities are united in opposing natural resource exploitation in northern Huehuetenango and beyond, and that gives them hope.

“If we continue together, organized and united, there will be change,” says Velásquez.

Other Special Reporting Initiatives Articles by Sandra Cuffe

Nickel Mine, Lead Bullets: Maya Q’eqchi’ seek justice in Guatemala and Canada

Mining and Energy Contracts under Investigation as Corruption Scandals Rock Guatemala