Dysfunction plagues DRC’s logging industry, say conservation and watchdog groups, but the government and timber companies want to grow the sector.

Little of the timber from the Democratic Republic of Congo that finds its way onto international markets can be considered legal, according to a pair of advocacy organizations that recently investigated the forestry sector in the country.

In rebuttal, the logging industry in DRC and the government itself have argued that, if anything, timber is still a largely untapped resource that should grow to fuel the impoverished country’s development. According to data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) accessed through Global Forest Watch, the forestry sector was worth around $85 million to DRC’s economy, or about 0.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), in 2011.

Global Witness and Greenpeace published separate reports in the past month detailing the weak forestry oversight that, they contend, allows companies to shirk their social responsibilities to communities, harvest timber beyond the quotas set by their permits if they have them in the first place, and avoid paying taxes to the government, even as they ship the bulk of their harvest abroad to China, the U.S., and the EU.

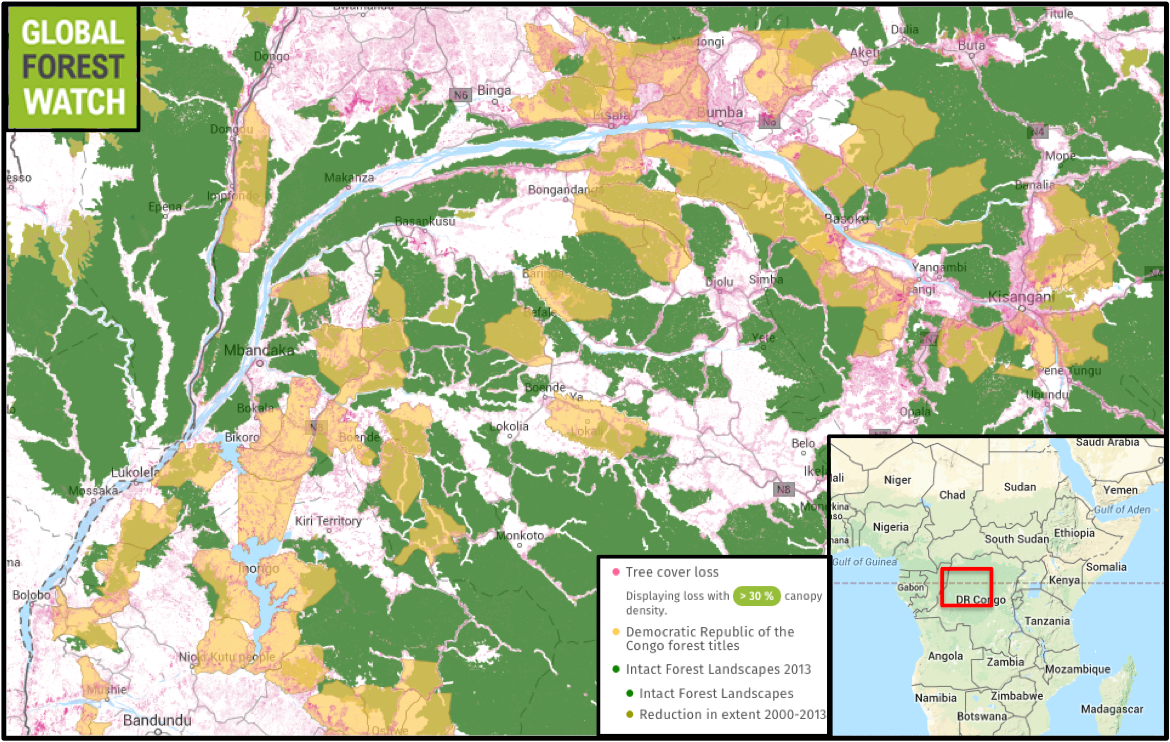

The map above from Global Forest Watch shows the bulk of the DRC’s government-issued concessions for selective logging. Also shown are areas of recent tree cover loss and intact forest landscapes (IFLs), which are areas of primary forest large enough to retain their original biodiversity levels. Many of the concessions overlie IFLs, some of which show degradation since 2000. Click to enlarge.

A massive central African country roughly the size of the United States east of the Mississippi River, DRC is second only to Brazil in the area of the world’s tropical forests – around 7 percent – it contains. And yet, the officials in charge of protecting those vast resources aren’t doing their jobs, said Raoul Monsembula, coordinator of Greenpeace Africa’s DRC program.

“The biggest problem is that the administration is not working at all,” Monsembula told mongabay.com. “The logging companies know that and are doing what they want, as corruption is the norm now.”

That corruption manifests itself as payments from logging companies to turn a blind eye to permit violations, underreporting how much wood they’ve cut, and not sticking to contracts signed with local communities, write the authors of the Greenpeace report, “Trading in Chaos.”

The results of third-party monitoring in Congo support these conclusions, said Essylot Lubala, coordinator of the monitoring group in DRC known by its French name, Observatoire de la Governance Forestière, which is funded by the EU.

“The illegalities found in the forest sector and in other sectors stem from weak governance in general,” Lubala told mongabay.com in an email. “This means that government officials in the DRC must make an effort to actually implement the laws that exist.”

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are endangered apes whose entire species is contained in the DRC. Most of the country’s logging concessions are located within their range. Photo by John C. Cannon.

The Global Witness publication tabulated independent monitoring reports from 2011 to 2014 and found that all 28 visits to industrial logging concessions in DRC turned up questionable practices.

However, Lubala did say that accreditation schemes, such as those set forth by the Forest Stewardship Council, have potential.

“Increasingly we find that companies whose concessions are engaged in forest certification are beginning to make noteworthy efforts,” Lubala said.

SODEFOR, a subsidiary of Norsudtimber based in Liechtenstein, is the largest timber company in DRC, operating around 2.3 million hectares – an area larger than Belize or the U.S. state of New Jersey. Spokesperson Filomena Amaral said that the company has “always complied” with forestry laws in DRC. (It is not a member of the Forest Stewardship Council.) Furthermore, Amaral said that government officials would have sanctioned SODEFOR had it broken the law.

Mongabay.com’s request for comment from two other companies mentioned in the reports, Cotrefor and Siforco, went unanswered.

Amaral refuted the Global Witness claim that SODEFOR harvests timber without permission, saying, “It is unimaginable that the Congolese State allows a company to operate without a permit.”

Global Witness was also critical of the harvest by SODEFOR and other companies of a highly valued species of tree called Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata), listed as a protected species by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Also known as African Teak, it’s commonly used to build boats and furniture, as well as for flooring.

“Yes, SODEFOR sells Afrormosia, which is a protected species but the trade of which is not prohibited,” Amaral told mongabay.com. “CITES sets standards that regulate its trade and that we respect.”

Scientists consider commercial poaching to be the bonobos’ greatest threat at the moment, with habitat loss also contributing to the species’ significant decline over the past 20 to 30 years. Photo by John C. Cannon.

But Global Witness points out that DRC has been banned from selling any CITES-protected species stemming from the country’s problems with the illegal trade of natural resources including ivory, documented by the UN and the International Criminal Police Organization.

Global Witness and Greenpeace also found that many companies, including SODEFOR, don’t regularly pay their taxes. Prior research by Global Witness found that in 2012 less than 10 percent of forestry taxes that should have been paid actually were.

“Logging companies have been getting away with illegalities that have cost the DRC millions of dollars in lost taxes, as well as endangering the forest,” said Alexandra Pardal, campaign leader at Global Witness.

“While the forestry sector ought to be a significant source of income for the DRC government, enabling money to be spent on improved governance and enforcement, in practice tax avoidance is rampant, with the connivance of the authorities,” wrote the authors of the Greenpeace report.

SODEFOR maintains that it has always met its tax obligations.

In February 2015, DRC’s Minister of the Environment and Sustainable Development Bienvenu Liyota said tackling illegal timber exploitation in Congo would be one of his priorities as minister. But both Liyota and the country’s logging advocacy organization, la Fédération des Industriels du Bois (FIB), said that Global Witness and Greenpeace had exaggerated outlier cases of illegality in industrial logging.

And, in the recent statements, both parties argued that timber harvests should increase dramatically.

“DRC’s forests remain largely undervalued,” producing less than five percent of the volume of timber that Congo’s forests were capable of over the past 10 years, according to FIB. “The forestry sector constitutes an opportunity to help DRC to develop and its people to get out of the extreme poverty,” wrote FIB President Gabriel Mola Motya in a response to the report released on June 23.

Bonobos differ from chimpanzees both physically and behaviorally, having more gracile bodies and longer hair on their heads, as well as a matriarchal social structure. Photo by John C. Cannon.

But depending on the government to police the sector won’t work, Greenpeace’s Monsembula said. To see any change, he believes the consumer countries must employ the laws against illegal imports in their own countries. After China, the EU is the largest buyer of DRC’s timber, with France importing more than 26,000 metric tons in 2013 and 2014.

“For those exports to occur there must be traders willing to trade in timber of illegal, or at least dubious, origin, and governments in importing countries unable to implement and enforce EU and international laws to prevent those transactions,” Monsembula said in a press release.

The Greenpeace report points out that, although the EU Timber Law (EUTR) requiring timber operators and traders to verify the source of their timber has been in place for several years, complementary French legislation allowing enforcement didn’t pass until late 2014. The report states that no inspections have occurred in France.

“I think it has to begin in those countries because if they became more demanding about which timber they buy, that will help us,” Monsembula said.

Global Witness’s Pardal echoed his sentiments: “Our figures show that the well-documented impunity in the logging sector has not deterred European timber traders from importing timber from DRC. We are asking EU member states – and in particular France – to apply the EU Timber Regulation [EUTR] and to investigate these imports.”

Citations:

Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute and Transparent World. 2014. Intact Forest Landscapes: update and reduction in extent from 2000-2013. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on July 08, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch onJuly 08, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.

“Managed forests.” World Resources Institute. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on July 08, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.