Liberia is home to pygmy hippos (Choeropsis liberiensis or Hexaprotodon liberiensis), which are listed by the IUCN as Endangered.

A swathe of no-deforestation policies by major commodities producers and suppliers in recent years brought fresh hope that genuine progress to curb rampant forest destruction was in full flow.

Despite the huge efforts to attain these deals, some argue the bulk of the hard work lies ahead in monitoring and ensuring these ambitious commitments are followed through.

That is a challenging enough endeavor for palm oil giants Golden Agri-Resources (GAR) and Wilmar with their vast chain of suppliers in Indonesia. But production is global these days and both have investments in projects in Africa, the so-called new frontier of production.

Both projects are covered by the companies’ no-deforestation policies and both have attracted criticism recently, particularly regarding the correct implementation of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of affected communities.

Some NGOs have suggested these persistent problems indicate no lessons have been learned from years of bad practice in Indonesia that provoked catastrophic levels of forest destruction.

A report from the Forest Peoples Programme (FPP) published this month claims that Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL) – a majority of which is controlled by GAR – has for several years created division and conflict among communities while developing its palm oil project in the country’s southeast.

Hollow Promises: An FPIC assessment of Golden Veroleum and Golden Agri-Resource’s palm oil project in Liberia says that thousands of hectares of forests have been cleared despite being the subject of numerous disputes between communities and home to endangered species including the chimpanzee. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) requested a freeze on work on the plantation in 2012 following community complaints before it recommenced in 2013.

“It is true to say that the palm oil industry has been synonymous with bad environmental and human rights practices for some time now, and everyone is keen to see some good news,” said Tom Lomax, a human-rights lawyer with FPP.

“However … the far greater risk is the one borne by communities duped by false promises into permanent dispossession from their lands, and the destruction of their forests, wetlands and strongly land- and forest-connected cultures.”

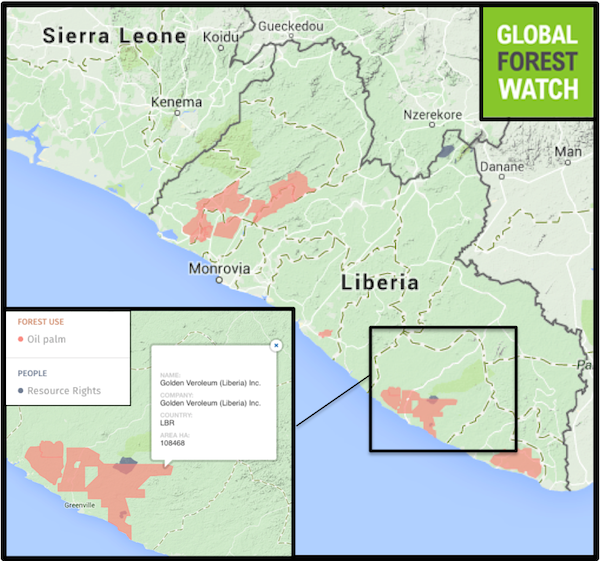

A map from Global Forest Watch identifies areas set aside by the government for oil palm and for community forests in Liberia. Oil palm concessions cover more than 20 times as much land as community forests. Click to enlarge.

In Uganda, farmers from Kalangala and Buvuma Islands in Lake Victoria learned last week that they will be able to pursue a case in court where they will seek compensation and the return of their homes after their allegedly unlawful displacement three years ago in the development of a 40,000-hectare oil palm project co-owned by Wilmar.

The legal process was launched in February and Anne Van Schaik, an accountable finance campaigner with Friends of the Earth Europe, which is supporting the case, said the idea is for it to evolve into something akin to a class action with residents who feel they have not received justice encouraged to sign up.

“This is quite a simple project in many ways. Forty-thousand hectares split between the two islands and the mainland,” she said. “Yet they [Wilmar] have not been able to develop it properly and have caused the same social problems as we witnessed in Indonesia.”

Both companies reject the latest criticisms and believe they are being unfairly targeted. Wilmar released a response to the launch of the court action in February denying it was responsible. The company also says it is investigating claims of illegal forest clearance in its Indonesia plantations said to have taken place after its no-deforestation pledge signed in December 2013. It recently launched a new monitoring tool it says will help enforce its ambitious commitments.

Virgil Magee, GVL’s head of corporate communications, said the company was disappointed with the FPP report and that, due to the fact the NGO researchers had not themselves been on the ground for 18 months, their claims “reflect a lack of understanding of the communities of South East Liberia or how GVL works with them.”

GVL previously said it welcomed a progress report from Greenpeace published at the end of last year that praised some of the company’s environmental initiatives but also said there was still work needed on implementing FPIC, an area the company acknowledged it had been weak on in the past.

While producers criticize NGOs for lacking up-to-date information, those attempting to monitor their operations have problems gaining access. Greenpeace and others rely on local organizations, while in Uganda, Friends of the Earth say their networks have problems carrying out their work and campaigner David Kureeba was arrested.

The Forest Trust (TFT) helps companies implement their policies and provides logistical support on the ground, but the Ebola crisis in Liberia has meant it too has not been able to have anybody in the country since August.

TFT founder Scott Poynton said that while GAR and Wilmar are “no angels,” some credit must be given in particular to GVL for its efforts to improve its operations.

“Anybody in their right mind would have walked away from GVL a long time ago, but [GAR chief executive] Franky Widjaja is genuinely keen to make this project an example for others to follow,” Poynton said.

Poynton said the lack of trust between many in the NGO community and producers is understandable but regrettable. But while companies such as GAR and Wilmar might feel they are getting unfairly singled out because of their decision to make ambitious commitments, those keen to see an end to years of environmental destruction and see genuine change in the behavior of major producers and suppliers feel there is still a lot to be mistrusting of.

Correction: Franky Widjaja is the chief executive of GAR. Not Freddy Widjaja.

Disclosure: In late December 2015, it came to light that the author was a public relations contractor for Greenpeace at the time of this story’s publication. The author says this affiliation did not influence his reporting. The story was independently edited and fact-checked by a Mongabay editor.