Large trees store store up to half the above-ground biomass in tropical forests, reiterating their importance in buffering against climate change, finds a study published in Global Ecology and Biogeography.

The research, which involved dozens of scientists from more than 40 institutions, is based on data from nearly 200,000 individual trees across 120 lowland rainforest sites in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It found that carbon storage by big trees varies across tropical forest regions, but is substantial in all natural forests.

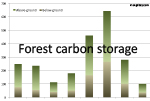

African rainforests, with an average of 418 tons of above-ground biomass per hectare, stored the most carbon. Big trees — defined as those measuring at least 70 cm in diameter at breast height — accounted for an average of 44 percent of African forests’ biomass. Other research has suggested that the preponderance of large trees in African forests is due to the abundance of large herbivores, which suppress smaller trees.

Asia was second with an average of 393 tons, of which large trees accounted for 154 tons or 39 percent of total above ground carbon. Latin America averaged 288 tons per hectare, about a quarter of which occurred in large trees.

Above-Ground Biomass in Tropical Forests (Tons/Ha) for Small Trees and Big Trees is Asia, Africa, and Latin America

The findings emphasize the importance of big trees, which typically dominate old-growth forests.

“Big trees represent less than 5% of stems, but store up to 50% of tropical forest biomass,” lead author Ferry Slik of China’s Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden told mongabay.com. “This makes tropical forest biomass storage very vulnerable to global change, especially if droughts would become more frequent and intense.”

Rainforest above-ground biomass by region

Big trees also have important ecological functions, offering niche habitats for wildlife and providing abundant fruit, foliage, and flowers.

Yet big trees are particularly at risk due to their attractiveness to loggers, who typically target the largest and oldest trees in selective logging operations. Big trees are also especially vulnerable to ecosystem change, including drought, increased incidence of wildfires, edge effects, and disease, according to a 2012 paper published in the journal Science. Taken together, the new study adds urgency to calls to better protect old-growth forests for climate stabilization and conservation of biodiversity.

“Once lost, it takes hundreds of years to get these big trees back, so we’d better take good care of them,” said Slik.

CITATION: J.W. Ferry Slik at al (2013). Large trees drive forest aboveground

biomass variation in moist lowland

forests across the tropics. Global Ecology and Biogeography.

Related articles

Experts: sustainable logging in rainforests impossible

(07/19/2012) Industrial logging in primary tropical forests that is both sustainable and profitable is impossible, argues a new study in Bioscience, which finds that the ecology of tropical hardwoods makes logging with truly sustainable practices not only impractical, but completely unprofitable. Given this, the researchers recommend industrial logging subsidies be dropped from the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program. The study, which adds to the growing debate about the role of logging in tropical forests, counters recent research making the case that well-managed logging in old-growth rainforests could provide a “middle way” between conservation and outright conversion of forests to monocultures or pasture.

Industrial logging leaves a poor legacy in Borneo’s rainforests

(07/17/2012) For most people “Borneo” conjures up an image of a wild and distant land of rainforests, exotic beasts, and nomadic tribes. But that place increasingly exists only in one’s imagination, for the forests of world’s third largest island have been rapidly and relentlessly logged, burned, and bulldozed in recent decades, leaving only a sliver of its once magnificent forests intact. Flying over Sabah, a Malaysian state that covers about 10 percent of Borneo, the damage is clear. Oil palm plantations have metastasized across the landscape. Where forest remains, it is usually degraded. Rivers flow brown with mud.

Big trees, like the old-growth forests they inhabit, are declining globally

(01/26/2012) Already on the decline worldwide, big trees face a dire future due to habitat fragmentation, selective harvesting by loggers, exotic invaders, and the effects of climate change, warns an article published this week in New Scientist magazine. Reviewing research from forests around the world, William F. Laurance, an ecologist at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, provides evidence of decline among the world’s ‘biggest and most magnificent’ trees and details the range of threats they face. He says their demise will have substantial impacts on biodiversity and forest ecology, while worsening climate change.

Logging of primary rainforests not ecologically sustainable, argue scientists

(01/25/2012) Tropical countries may face a risk of ‘peak timber’ as continued logging of rainforests exceeds the capacity of forests to regenerate timber stocks and substantially increases the risk of outright clearing for agricultural and industrial plantations, argues a trio of scientists writing in the journal Biological Conservation. The implications for climate, biodiversity, and local economies are substantial.

Old trees necessary for nesting animals

(10/17/2011) Aged, living trees are essential for over 1,000 birds and mammals that depend on such trees for nesting holes, according to a study in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. In much of the world, tree-nesting animals depend on holes formed through maturity and decay—and not woodpeckers—requiring standing old trees.

Old-growth forests are irreplaceable for sustaining biodiversity

(09/14/2011) Old growth rainforests should be a top conservation priority when it comes to protecting wildlife, reports a new comprehensive assessment published in the journal Nature. The research examined 138 scientific studies across 28 tropical countries. It found consistently that biodiversity level were substantially lower in disturbed forests.

Temperate forests store more carbon than tropical forests, finds study

(07/17/2009) Temperate forests trump rainforests when it comes to storing carbon, reports a new assessment of global forest carbon stocks published July 14th in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The findings have important implications for efforts to mitigate climate change by protecting forests. Sampling and reviewing published data from nearly 100 forest sites around the world, Heather Keith, Brendan G. Mackey, and David B. Lindenmayer of Australian National University found that Australia’s temperate Eucalyptus forests are champions of carbon storage, sequestering up to 2,844 metric tons of carbon per hectare, a figure that far exceeds previous estimates. These forests, located in the Central Highlands of Victoria in southeastern Australia, are dominated by giant Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans) trees, which can reach a height of 320 feet and live for more than 350 years. They are also favored by the timber industry. Mountain Ash forests have been widely logged across Australia, with only limited old-growth stands remaining.

(06/09/2009) A global framework on climate change must immediately halt deforestation and industrial logging of the world’s old-growth forests, while protecting the rights of forest communities and indigenous groups, said a broad coalition of activist groups in a consensus statement issued today at U.N. climate talks in Bonn Germany. The statement said the successor treaty to the Kyoto Protocol should not include mechanisms that allow industrialized countries to “offset” their emissions by purchasing carbon credits from reducing deforestation in developing countries, a position that puts the coalition at odds with larger environmental groups who say a market-based approach with tradable credits is the only way to generate enough money fund forest protection on a global scale.