During the smoky season, or “musim kabut” as it is called in Indonesia, skeletons of leaves fall from the sky and disintegrate like melting snowflakes in children’s hands.

Historically, Indonesia’s smoky season has peaked at the end of the dry season (September-October), just before the monsoon rains arrive. This year the dry season just began, and yet Singapore’s PSI (Pollutant Standard Index) record has already been broken – reaching a new high of 401 (Hazardous) on June 21, 2013. The air pollution in Peninsular Malaysia has also spiked to an all-time-high, resulting in Prime Minister Najib Razak declaring a state of emergency in Muar and Ledang districts on June 23, 2013.

Although the fires are of immediate concern at the regional level, they are quite disconcerting at the global scale.

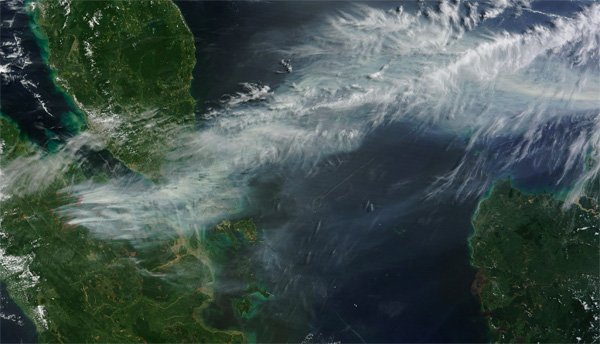

Smoke – visible from outer space – rises from Sumatra on June 19, 2013. (Photo source: NASA)

Indonesia’s Inferno

The fires originate in one of Earth’s carbon super-sinks: peat swamps. Hidden underneath Sumatra’s lowland rainforests are thousands of years of partially-rotted tree trunks, branches, and leaves which never fully decomposed after their submersion into water. This dark under-world has the potential to become an inferno when exposed to air and ignited. Thus, as Indonesia’s peatlands are drained and burned, one of the world’s greatest long-term carbon sinks is being transformed into a rapid carbon source.

Scientists estimate that during the Indonesian fires of 1997, between 0.81-2.67 gigatons of carbon were released into Earth’s atmosphere (Page et al 2002). This is comparable to 13-40% of the fossil fuels emitted globally that same year, catapulting Indonesia to be ranked the world’s third highest emitter of greenhouse gases (after China and the USA) according to some indices.

The link between greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, and sea-level rise is worrisome for Indonesia, a nation comprised of more than 13,000 islands.

Responding with REDD+

In response, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono announced in 2009 at the UNFCCC Climate Change Conference that Indonesia would aim for a 26% reduction (41% with international help) in greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2020, with a parallel goal of achieving a 7% GDP annual growth rate by 2014.

These are important goals for Indonesia. But what practical strategies can the world’s fourth most populous country take to reduce its impacts on the climate while simultaneously improving national living standards?

One strategy being pursued is a mechanism known as REDD+, or Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. REDD+ is envisioned as a form of ‘payments for environmental services’ in which high-emission countries and companies pay rainforest-rich nations and communities to conserve forests, thus ‘offsetting’ carbon emissions in one location through the sequestration of carbon in another.

Can market-based conservation help save Sumatra and Borneo’s peat swamps – home to orangutans – from market-driven demand for timber, paper, and palm oil? (Photo: Wendy Miles)

To date, over $1.4 billion USD has been invested to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest fires in Indonesia. Investors include Norway, Australia, Germany, United States, United Kingdom, France, Denmark, South Korea, and Japan – as well as private companies such as Merrill Lynch, the Marubeni Corporation, Macquarie, and Gazprom. Indonesia now hosts more than fifty international REDD+ carbon-offsetting pilot initiatives that promise potentially billions of dollars worth of investments.

But the haze looming over Sumatra confronts REDD+ investors and Indonesia with the contradictions of market-based solutions.

The ‘Corporate Carbon Cycle’

Using NASA’s Active Fire Data and the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry’s concession maps of Riau, the World Resources Institute has shown that 52% of last week’s fires were on timber and oil palm concessions. Ironically, the two corporations holding over half of these concessions are Sinar Mas and Raja Garuda Mas International (RGM) – both of which have been pursuing carbon-offsetting initiatives in Riau Province.

Sinar Mas funds the “Kampar Carbon Reserve Project” and the proposed “Giam Siak Kecil-Bukitbatu Biosphere Reserve REDD+ Pilot Project”. Sinar Mas’s subsidiaries include PT SMART (one of the country’s largest palm oil companies) and Asia Pulp & Paper (one of the world’s largest paper and pulp companies).

Asia Pacific Resources International Holdings, Ltd. (part of RGM), operates the world’s largest pulp mill in Riau. In the same province they have worked to establish the controversial “Sustainable Peatland Management Model” project involving the creation of a ‘buffer’ of non-native Acacia trees (harvested for pulpwood) along the border of Kampar Peninsula, one of the last habitats of the critically endangered Sumatran tiger.

These companies and others are working to incorporate carbon-offsetting into their corporate social responsibility programs. Unfortunately, the emissions associated with this week’s blazes are sure to outweigh the potential offsets of current REDD-related activities in Riau Province.

Smoke Signals over Sumatra

In the coming weeks there will be attempts to pinpoint the source of Sumatra’s peatland fires. Tracking the culprits has proven difficult in years past, as these fires are not isolated events and peat can actually smolder belowground for months or even years before resurfacing into flames. Accusations already abound against Indonesia’s conglomerates, palm oil companies, smallholder farmers, and migrants squatting on concessions. Some of the accused are trying to increase profit margins, while others are struggling to make a daily living. But they all share the same market logic that underlies the REDD+ initiatives.

Some people will interpret these fires as an example of Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons. The rational individual (e.g. the Sumatran farmer or Indonesian corporation) will make ever-increasing demands on natural resources until the expected costs of his or her actions equal the anticipated benefits. Prioritizing personal interests, individuals sharing the commons (e.g. Indonesia) ignore the impacts of their actions on others (e.g. Singapore). In the end, everyone suffers.

But Hardin’s thesis is an over-simplification of reality. Decades of research have shown that societies repeatedly overcome the risk of such tragedies – finding ways to communicate, collaborate, and sustainably manage their natural resources. The late Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom recognized that the ‘Global Commons’ presents humanity with a new challenge. Earth’s atmosphere is a case in point. Can we come together as nations, corporations, organizations, and individuals to build an atmospheric ethic?

Wendy Miles researches the political ecology of market-based conservation in Indonesia’s peatlands. Micah Fisher has long worked and lived in Indonesia. Both Miles and Fisher are PhD students at the University of Hawaii’s Geography Department.

Editor’s note: views expressed in this op-ed are those of the authors alone.

Related articles