“Kansas Kids,” in Lakin, Kansas, three children prepare to leave for school wearing goggles and homemade dust masks to protect them

from the dust in 1935. Courtesy of Joyce Unruh; Green Family Collection.

The Dust Bowl, a film by Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan, and The Dust Bowl: An Illustrated History, a book authored

by Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns, chronicles the worst man-made ecological disaster in American history. Told in first-person narrative by survivors of the

Dust Bowl and brought to color through vivid storytelling and over 300 rare archival photos, these two combined efforts must be watched and read by those

concerned with our human impact on Earth.

-

“And they might last two or three days. One day my mother marked twenty-one days on the calendar that we had sandstorms every day… And you

still had the feeling, whether you would admit it, that something was going to run over you and crush you.” – Floyd Coen, Kansas

“Oklahoma dust storm,” FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein captured this photograph of Art Coble and his sons, south of Boise City,

Oklahoma, in April 1936. Courtesy of Library of Congress

Vivid interviews with twenty-six survivors of those hard times, combined with dramatic photographs and seldom seen movie footage, bring to life stories of

incredible human suffering and equally incredible human perseverance. The Dust Bowl

and The Dust Bowl: An Illustrated History describe a

morality tale about our human relationship to the land that sustains us. Yet it is also a story of how we neglected this same source of sustenance –

the land – causing us and the ecosystems we depend on great and permanent harm. This film is a must see and this book is a must read.

-

“Let me tell you how it was. I don’t care who describes it to you, nobody can tell it any worse than it was. And no one exaggerates; there

is no way for it to be exaggerated. It was that bad.” – Don Wells, Oklahoma

By 1880s, the immeasurable bison herds of the Great Plains had been slaughtered and the Beef Bonanza began. Then severe winters killed the cattle herds

bankrupting the cattle industry. Next the homesteaders moved in with promises of an Eden where any person, whether a suitcase in-town farmer or a rugged

homesteader, could feed their family and make money off the land. Fueled by the global wheat boom of the 1910s and 1920s, the “Great Plow-Up”

began when homesteaders plowed under tens of millions of acres of native buffalo grass in the Southern Great Plains for wheat production.

-

“This wind-driven dust, fine as the finest flour, penetrates wherever air can go.” – Caroline Henderson, Oklahoma

“Dark Day in Ulysses,” the huge Black Sunday storm – the worst storm of the decade-long Dust Bowl in the southern Plains – as it

approaches Ulysses, Kansas, April 14, 1935. Daylight turned to total blackness in mid-afternoon. Courtesy of Historic Adobe Museum

Then the Great Depression began, and wheat prices fell, sometimes 87% or more off their peak prices per bushel, while at the same time a decade-long

drought lasting from 1930 to 1940 also began.

With too much wheat under crop, most of the native grasses plowed under, and drought occurring, black dirt and sand dust bowl storms began to ravage the

southern Great Plains. These storms could be 100 miles long with 60 mile an hour winds and would turn day into night, covering crops, destroying homes, and

in the worst cases smothering all life in their path.

- “It was just unbelievable. It’d blister your face. It would put your eyes out.” – Pauline Robertson, New Mexico

The statistics are staggering. More than 850 million tons of topsoil blew away in single year. One-quarter of the Dust Bowl’s regions inhabitants

moved away. 14 million grasshoppers per square mile descended on parched fields.

-

“And I think it carried with it a feeling of, I don’t know the word exactly, of almost being…evil.” – Dorothy Williamson,

Colorado

“Black Sunday in No Man’s Land,” during the decade-long drought that turned the southern Plains into the Dust Bowl, the hardest

hit area was centered on Boise City, Oklahoma, in a part of the Panhandle formerly known as No Man’s Land. And the worst storm of all hit on

Palm Sunday, April 14, 1935—a day remembered as Black Sunday. Here the storm sweeps over a farmstead on its way toward Boise City. Courtesy of Associated Press

Black Sunday: The Dust Bowl Hurricane

Sunday, April 14, 1935 was the worst Dust Bowl storm on record. That afternoon, while families were enjoying their day of respite, the worst Dust Storm on

record crowded out the sun, and turned night into day. This storm had winds in excess of 65 miles an hour and was 200 hundred miles. It was so dark people

could not see their hand in front of their face. Stinging dust blistered their faces, making breathing difficult. The Black Sunday Dust Bowl was like a

tornado laying on its side, rumbling through town and field, covering everything in its path with thick dust. The storm was so strong that it even covered

politicians’ desks with dust far away in Washington DC.

“Kansas Church and a Black Blizzard,” the huge Black Sunday storm – the worst storm of the decade-long Dust Bowl in the southern Plains

– just before it engulfed the Church of God in Ulysses, Kansas, April 14, 1935. Daylight turned to total blackness in mid-afternoon. Courtesy of Historic Adobe Museum.

“Dusted Out Farmstead,” an abandoned farm north of Dalhart, Texas, 1938. FSA photographer Dorothea Lange took the picture. Courtesy of Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress.

Permanent Economic Impact

Dr. Richard Hornbeck sums up the permanent negative economic impact of the Dust Bowl best in his paper The Enduring Impact of the American Dust Bowl: Short- and Long-Run Adjustments to Environmental Catastrophe

where he states:

-

In many regions, over 75% of the topsoil was blown away by the end of the 1930s…there were severe long-term economic consequences of the Dust

Bowl.

By 1940, counties that had experienced the most significant levels of erosion saw a greater decline in agricultural land values. The per-acre value of

farmland declined by 28% in high-erosion counties and 17% in medium-erosion counties, relative to land value changes in low-erosion counties. Even over the

long-term, the full agricultural value of the land often failed to recover. In highly eroded areas, less than 25% of the original agricultural losses were recovered.

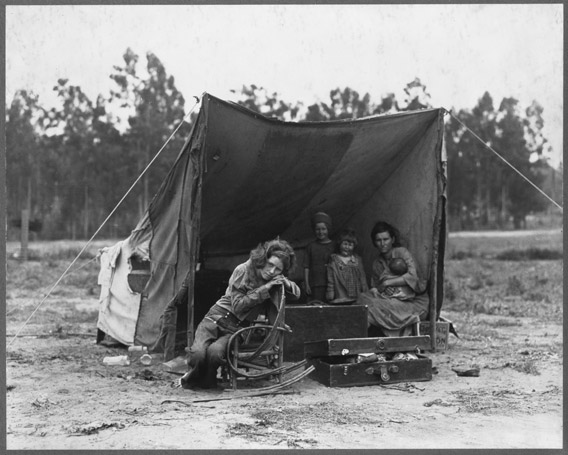

“Florence Thompson and Children,” FSA photographer Dorothea Lange came across Florence Thompson and her children in a pea pickers’ camp

in Nipomo, California, in March 1936. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The Great American Drought, 2012

Under these same Southern Great Plains sits the Ogallala aquifer. It is about 100 feet deep, and is from glacial melt over the past tens of thousands of

years. It is very slowly recharged based on annual precipitation. Yet right now, it is now being mined with its water pumped to the surface to feed

unsustainable agriculture and land-use practices on the same land that suffered from the Dust Bowl 80 years ago.

It is estimated that possibly 20 to 50 years of water are left for these 8 states. When the water is gone, the resulting impact could result in Dust Bowl

like ecological consequences.

For example, August 17, 2012, there were 1,692 counties across 36 states in the US were legally declared “natural disaster areas”. The Great

American Drought of 2012 at this point covered 62% of the lower 48 states. This area, 1.2 billion acres, is 12 times larger than the area that was impacted

by the Dust Bowl.

Interview: Ken Burns, Film Producer and author,

The Dust Bowl

and The Dust Bowl: An Illustrated History

Gabriel Thoumi, mongabay.com: Thank you Mr. Burns for your support of Mongabay.com and your dedication to mitigating climate change. Thank you for bringing the Dust Bowl to

life by chronically survivors’ stories. What were you emotions like producing the Dust Bowl, revisiting such powerful memories and hearing many

powerful individuals stories related to climate change in the American prairies during the 1930s while the great 2010-2012 North American Drought was

occurring?

Ken Burns:: I am drawn to choose a subject by the quality of the stories. The Dust Bowl has an emotional archaeology about it. In our documentary, two dozen survivors

of the Dust Bowl tell their epic and tragic stories. It is the worst American man-made ecological disaster overlaid by the worst American-made disaster,

the Great Depression.

Gabriel Thoumi, mongabay.com: If you could tell the story about our current attempts to mitigate climate change, what would it look like? How would it feel and sense? How can

do we empower storytelling to encourage leadership in mitigating climate change?”

Ken Burns:: Ecclesiastes says nothing is new under the sun. Human nature remains the same. In every grain of human sand we examine, we sense human nature

again. We watch these cycles of boom and bust throughout our American history. Because of this it is more urgent to remember the past, to inform the

present.

Yet now there are a million straws mining the vast Ogallala aquifer – a huge cistern of glacial melt. The water will run out, and the Dust Bowl may

return with the Southern Central Plains possibly becoming a Sahara.

The Dust Bowl can happen again.

Gabriel Thoumi, mongabay.com: The Dust Bowl

and The Dust Bowl: An Illustrated History present a remarkable, vivid, painted tale. Painful, poignant, filled with living history, and more relevant today more than ever. It will

bring you to tears mourning those who suffered and died during the Dust Bowl and it will serve as a dire warning for us to care for our land today because

our land is what sustains us.

You must watch the The Dust Bowl and read The Dust Bowl: An Illustrated History .

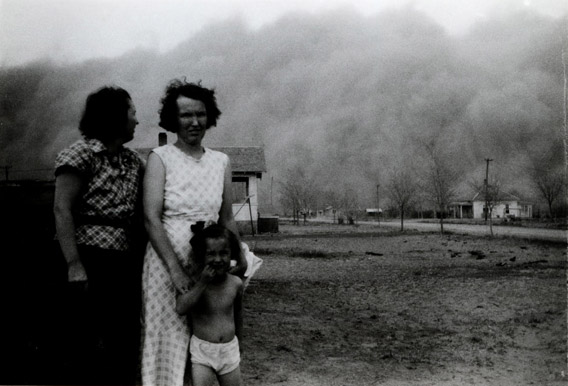

“Watching a Dust Storm’s Approach,” as a black blizzard rolls in to Ulysses, Kansas, two women and a girl pose for a photograph

before taking shelter. Courtesy of Historic Adobe Museum

Gabriel Thoumi, CFA is a member of the Global Association of Risk Professionals and a frequent contributor to Mongabay.com.

Related articles