Borneo rainforest. Photos by Rhett A. Butler. |

| In late May I had the opportunity to fly from Kota Kinabalu in Malaysian Borneo to Imbak Canyon and back. These are some of my photos. Note that higher quality versions of these photos (and 2,500 more) will be posted on mongabay.com in coming weeks.

UPDATE 7/3/12: To clarify, these pictures do not depict anything illegal. Conversion of forests into oil palm plantations in Sabah — unlike some other parts of Southeast Asia — has been mostly done through a land zoning process that dates back decades. Additionally, Sabah’s legal forest reserve is set aside for forest management (logging) — not conversion to oil palm plantations (with the exception of the 100,000 ha within the Yayasan Sabah concession). The point of this post is to show the transition from primary lowland forest to logging areas to oil palm concessions via an overflight, not serve as a broader commentary on Sabah’s forest management practices. I will be running a longer story later this month which will provide a more detailed look at forestry in Sabah. Meanwhile look for an upcoming peer-reviewed study that will quantify the recent history of forest cover in Sabah, Sarawak, and Brunei. Finally this post originally contained two pictures of orangutans from Central Kalimantan (Indonesia) but due to objections from a representative at the Borneo Conservation Trust, they have been replaced with a single picture of an orphaned orangutan from Sabah. |

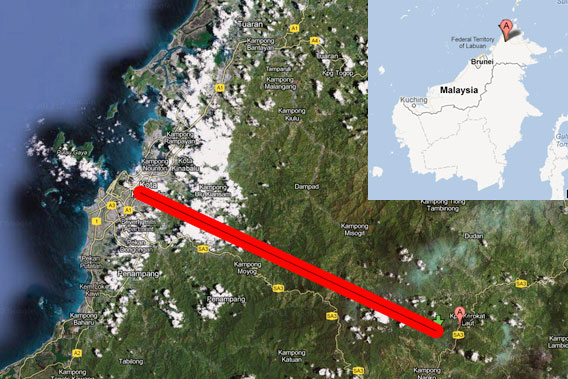

The generalized flight path from KK to Imbak and back. Courtesy of Google Earth. |

Borneo is the third largest island in the world. It is governed by three countries: Indonesia, which controls 72.6 percent of its landmass across four ‘Kalimantan’ provinces; Malaysia (26.7 percent in the states Sabah and Sarawak); and the sultanate of Brunei (0.6 percent).

Historically Borneo was covered by a range of habitats, including dense tropical rainforests, swampy peatlands, and natural grasslands.

Orphaned orangutan in Sabah. |

Borneo’s ecosystems support a wide range of species, none of which is better known than the orangutan. Borneo has perhaps 90 percent of the world’s surviving wild orangutans.

The Malaysian state of Sabah, in northeastern Borneo, has roughly twenty percent of the island’s orangutans, as well as small populations of endangered elephants and Sumatran rhinos.

Remote primary forest in Sabah |

Research has shown Sabah’s rainforests to be the most biologically diverse in Borneo and some of the richest on the planet. But like the rest of Borneo, Sabah’s lowland forests have been aggressively logged for timber and then converted for oil palm plantations.

Imbak Canyon |

Imbak Canyon is one of the last areas of primary lowland rainforest in Borneo, an island that just thirty years ago still have large tracts of unlogged forest.

Imbak Canyon |

Imbak was also slated for logging but when a 1992 scientific expedition uncovered the valley’s extensive biological richness, the logging plan was pulled. The area was subsequently set aside as “Class I” forest for strict protection. Since then other tracts of lowland forest — some of which were selectively logged in the past — have been set aside for protection.

|

Imbak lies in the Yayasan Sabah concession, an area of a million hectares of forest that was supposed to be sustainably managed for the benefit of the people of Sabah. For years the Yayasan Sabah concession funded scholarships and poverty alleviation programs but corruption and greed eventually led to overexploitation of the concession’s forests. As timber yields declined, so did the financial benefits for Sabahans. At the same time, ecosystem services were degraded, reducing the availability of clean, fresh water, especially in rural areas.

Logging road in Sabah

|

Most of Yayasan Sabah’s concession is commercially exhausted. To fund ongoing programs, Yayasan Sabah turned over 100,000 hectares of land for oil palm plantations. The rest of the concession is predominantly overharvested production forest but also some conservation areas, including Imbak, Maliau, and Danum Valley.

Once operational, Yayasan Sabah’ oil palm plantations are expected to generate more revenue than selective logging ever did. Some believe the success of oil palm may push Yayasan Sabah to convert additional areas of heavily degraded forest for plantations. The concern among some scientists however is that oil palm plantations are biological deserts relative to even heavily logged forest.

Oil palm plantation in Sabah

|

The transition from rainforests to an oil palm plantations follows a typical pattern. Forests — flat lowland areas are preferred — are selectively logged for high value timber. Subsequent harvests take smaller and less valuable trees until the area is commercially exhausted. Remaining trees are clear-felled and oil palm trees are planted. The usual lifespan of an oil palm plantation is 25-30 years. After that time, palm trees are cut down and the soil restored. The land is then replanted with palms for another cycle.

Outside the Yayasan Sabah is a sea of oil palm plantations. Today Sabah has roughly 1.5 million hectares of oil palm. Much of this is leased long-term to palm oil companies, meaning that it won’t be returned to forest.

Fire on an oil palm plantation in Sabah

|

Palm oil has generated tremendous wealth for the companies and families that used to run Malaysia’s logging industry, before it went into decline due to overharvesting. Palm oil has also boosted rural incomes for those who own land, but at the same time exacerbated social conflict, especially between communities and palm oil companies. Social conflict has been particularly intense in Sarawak.

Clear-cutting in Sabah

|

Oil palm expansion has also taken a toll on the environment, triggering severe water pollution (oil palm plantations typically make heavy use of chemical inputs), driving deforestation, and sparking killing of protected species that enter plantations.

While Sabah is reaching the limits of the area where new oil palm plantations can be established due to land zoning regulations, palm oil companies are expanding operations elsewhere, including Indonesian Borneo, other parts of Asia, and west Africa.

Hillsides stripped of their tree cover

|

Malaysia’s Land Development Authority (FELDA) — which functions as the third largest palm oil company in the world — last month carried out a public stock offering to raise money for overseas expansion.

In recent years the palm oil industry has come under fire from environmentalists for its role in forest and peatlands destruction. Green groups have adopted the orangutan as a symbol of palm oil opposition. The industry maintains its crop is a cheaper and more agriculturally productive crop than other oilseeds.

Palm oil is mostly used in cooking oil, processed foods, cosmetics, and cleaning agents. Future palm oil demand may be bolstered by use as a biofuel.

Oil palm plantations in Sabah

|

The palm oil sector is lobbying heavily to win acceptance of palm oil as a source of biofuel under low carbon fuel standards even though a number of studies have found that palm oil-based biodiesel fails to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions relative to conventional fossil fuels once deforestation is factored into lifecycle analysis. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently ruled that palm oil biodiesel shouldn’t qualify as a low carbon fuel.

Related articles

Palm oil giant moves forward on zero deforestation initiative

(06/05/2012) One of the world’s largest palm oil companies has become the first to identify and disclose high carbon forests and peatlands in its concessions. Golden Agri-Resources Limited (GAR), the owner of Indonesia’s palm oil giant PT SMART Tbk, on Monday published a carbon assessment of its holdings in Indonesian Borneo. The report is an important milestone under GAR’s forest conservation policy, which prohibits conversion of land with more than 35 tons of carbon per hectare and moves the company toward a zero deforestation target.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.