Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff on Monday revealed the details of her line-item veto to proposed changes to the country’s Forest Code, which governs how much forest landowners are required to preserve. Rousseff vetoed a dozen clauses of the revised Forest Code and modified several others. The bill now goes back to the Chamber of Deputies, followed by the Senate and House, before returning again to Rousseff. A final decision isn’t expected until after the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development.

Among the dozen clauses vetoed by Rousseff was a blanket amnesty for landowners who illegally cleared forest before July 2008. With the exception of some smallholders representing about a quarter of rural properties (determined on a municipality by municipality basis, depending on several factors), landowners will be required to restore deforested areas up to levels specified by the law, including along waterways. The version of the legislation passed by the House only required a ten meter wide zone of forest along rivers, but Rousseff extended the area to up to 100 meters for large rivers on properties owned by large producers, with more limited protected areas along smaller rivers and for smaller properties. Forests on hilltops and steep slopes must also be protected (deforestation on slopes and mountaintops over 1,800 meters in elevation before 2008 is exempted). Failure to meet Forest Code obligations will result in fines and loss of access to subsidized agricultural loans.

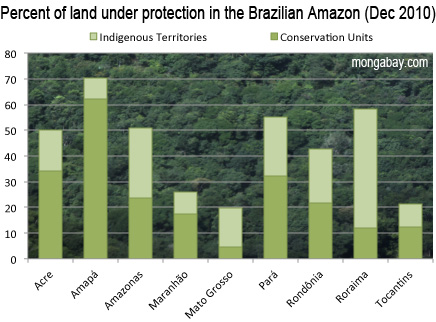

Percent of land under protection in the Brazilian Amazon as of December 2010. Related story. |

Rousseff maintained a provision that would allow the legal reserve requirement to fall from 80 percent to 50 percent in states where 65 percent of forest is locked up in protected areas and indigenous territories. The legal reserve is the proportion of land a property owner is required to maintain as forest. Controversially, the revised Forest Code allows landowners to plant exotic species like Eucalyptus, pine, oil palm, and coffee restore their legal forest reserve.

Rousseff eliminated a clause that would have exempted urban landowners from maintaining a legal reserve. She also nixed a paragraph that would have left mangroves without protection, although the bill’s text still allows opening up some areas for shrimp farms.

The new legislation also codifies the establishment of a land registry, known as the Cadastro Ambiental Rural or CAR, that requires ranchers and farmers to report the boundaries of their holdings to the government, which will enter the coordinates into the national deforestation tracking system. The government will then use satellite imagery on an ongoing basis to determine whether landowners are in compliance with the forest reserve requirement.

Rousseff’s version of the Forest Code now goes back to the House and Senate for approval. Her changes can be overturned by Congress by majorities in both chambers, but at present is appears unlikely that the Senate would overturn her line-item vetoes.

Gallery: Amazon deforestation Gallery: Amazon deforestation

|

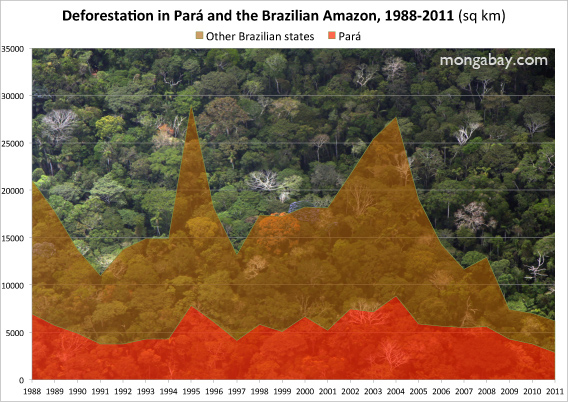

The Forest Code revision comes less than a month before Brazil hosts the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development. Environmentalists say the proposed relaxation of the Forest Code sends the wrong message ahead of the key environmental meeting and could eventually reverse Brazil’s progress in reducing its deforestation rate, which has fallen by 78 percent in the Amazon region since 2004.

“It is disappointing that President Rouseff has chosen not to take the opportunity to respect Brazilian public opinion by putting forward legislation that balances the needs of agriculture and forest protection in the Amazon,” Steve Schwartzman of the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) told mongabay.com. “In spite of her campaign promises, she has accepted amnesty for illegal deforestation and large-scale reductions in forest protection.”

WWF added that the partial vetoes, instead of an outright veto, creates unnecessary confusion on the law.

“President Rousseff’s statement today creates an uncertain future for Brazilian forests, considering the Congress could still cut forest protections even further,” said Jim Leape, WWF International Director General.

Scientists fear that continued deforestation could reduce the resilience of the Amazon to climate change, potentially tipping much of the ecosystem from rainforest to savanna and diminishing its capacity to generate rainfall, store carbon, and provide a refuge for wildlife.

Related articles