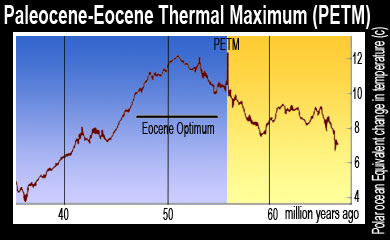

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a period of global warming that occurred nearly 56 million years ago due to massive releases of greenhouse gases, is frequently referenced as an analogue for projected climate change. However, recent findings suggest the current rate of carbon release is almost 10 times as rapid as at the peak of the PETM—and that biological systems may be significantly less able to adapt.

The PETM lasted roughly 170,000 years, raising Earth’s annual temperature an average of 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit). Experts are currently uncertain what caused the PETM, however the most widely accepted theory is that fire or volcanic activity released the potent greenhouse gas, methane, from organic-rich sediments; as temperatures rose, gas hydrates in deep ocean sediments could have broken down, releasing even more methane, which would have oxidized into carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The researchers explain that the carbon released during the PETM is equivalent to the amount of carbon that would be emitted if all known sources of fossil fuels were today burned. However, scientists now estimate that the current rate of carbon release is far more rapid.

The Paleocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum (Chart by R. Butler of mongabay.com) |

An international team of geologists supported by the National Science Foundation published their groundbreaking findings in Nature Geoscience. Prior studies of the PETM tested core samples from areas that were deep ocean floor 55.9 million years ago, however, acidification caused by greenhouse gases dissolves calcium carbonate, making the rate of emission difficult to determine. So, the geologists, based out of Penn State, decided to examine cores from an area in Norway that was a shallow sea bottom during the PETM. Unlike deep-sea cores, which generally have between 10 centimeters and a meter of core correlating with the PETM, the Spitsbergen cores allowed scientists to examine 150 meters (492 feet) of sediment from the PETM era.

“We were concerned with the fidelity of the deep sea records,” explains Lee Kump, professor of geosciences at Penn State, “The incomplete record makes the warming appear more abrupt.”

Instead, their findings suggest that warming in the PETM was more gradual than current climate change. Adds Kump, “Rather than the 20,000 years of the PETM which is long enough for ecological systems to adapt, carbon is now being released into the atmosphere at a rate 10 times faster.”

Using computer modeling to determine the timing and intensity of carbon release during the PETM, the scientists found that the rate of carbon release at the height of the PETM did not exceed 1.7 petagram of carbon per year. Current fossil fuel emissions now top 8 petagrams of carbon per year.

“Our findings suggest that humankind may be causing atmospheric carbon dioxide to increase at rates never previously seen on Earth, which would suggest that current temperatures will potentially rise much faster than they did during the PETM,” explains Dr. Ian Harding, a senior lecturer the University of Southampton’s National Oceanography Centre.

Related articles

=