In his concession speech after the 2010 mid-term elections, President Obama said

that prospects for meaningful U.S. climate change legislation are doubtful and will be for years.

With

the US and the international community unable to take even modest steps to

combat global warming, the State of California has stepped up in a big, big

way. Despite record unemployment rates, deficits and unemployment, California

voters trounced a measure that would have suspended AB 32, California’s

landmark climate change law. California’s AB 32 cap and trade program will soon

be the biggest market for compliance emission reductions outside of Europe. In

the wreckage of the Copenhagen talks and the new political landscape in

America, California is the most dynamic jurisdiction for climate change

implementation.

|

|

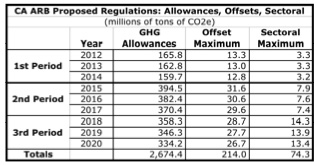

Just

days before the 2010 elections, California’s

regulatory body proposed regulations to implement cap and trade provisions of

AB32. One big question was whether California would allow regulated

entities to use any emission reductions from developing countries for

compliance. The pending rules answered that question by allowing limited carbon

credits into California from developing countries, provided an entire economic

sector in a given jurisdiction reduces emissions significantly below historical

levels. So-called “sectoral credits” are a significant leap forward in carbon

markets. The scale of mitigation for sectoral credits must go beyond simply

stopping emissions at a single location or project.

Sectoral

credits as envisioned in the California rules will demand scaled-down low-carbon

development of entire sectors across large geographic regions [Briefing Note on CA AB 32]. This is a

game-changing development for climate policy and finance. The historical

approach of using climate finance on project-specific activities is the core

operating procedure of the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism and

voluntary carbon credits. Now to access funds available under California’s cap and trade

program, states and provinces in developing countries at large must reduce

emissions. And given that the prospects for US legislation are pretty close to

nil, California’s new rules are a welcome bright spot and could be the basis

for linking with other international climate change policies.

California

Takes A Giant RED Step.

Click to enlarge |

Critically

important, California’s proposed regulations stated that the first sector

eligible for international offsets will be reducing emissions from

deforestation (RED). (For the policy wonks out there, yes that is only

one D. The draft regulations suggest California will probably focus on

deforestation first, before other issues such as degradation, soil, etc.). This

handshake, whereby California would pay states in Brazil, Mexico or Indonesia

to reduce deforestation, is a powerful endorsement of the work being done in

the Governors Climate and Forest Taskforce (GCF) and

in the reductions in deforestation already achieved by some key states and

provinces. If REDD+ was already an ember of hope for climate policy after the

dark days of Copenhagen’s failure, RED, at least in California, is now on fire. (In

an earlier article, I discuss how after Copenhagen, REDD+ emerged as the front-runner in international climate

change cooperation. California indicated it would accept up to 74.3

million tons of CO2 reductions from sectoral credits, and forests are the only

sector that is explicitly discussed in the regulations.

|

With

California voters backing cap and trade legislation and California regulators

blessing RED as the first option for sectoral offsets, what implications does

this have for international climate negotiations in Cancun, Mexico? Governments are meeting in Cancun for the 16th

Conference of Parties of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (known

as COP16). They are trying to resuscitate global climate change policy. The

signs from the first week of negotiation are mixed. REDD+ continues to make

substantial progress. The three pages of negotiating text on REDD+ in the 33

pages of key negotiations are largely free of disagreement, with one

major exception. Bolivia has insisted that REDD+ can not “constitute the

establishment or use of a market mechanism.” Bolivia doesn’t like markets. So

for now even though the negotiating documents are getting close to the

consensus needed to make them official decisions, REDD talks are stalled until

Bolivia changes its position. (Supporting Bolivia in this outlier mode is Saudi

Arabia.) Bolivia’s President Evo Morales is rumored to be attending, possibly

with other left-leaning Heads of State to make their case in person. The United States has also said

they won’t let any decision go forward on REDD+ without other concessions in

the negotiations. Notably, the United States wants more clarity on verification

and the role developing countries will play in mitigation. These are the same

issues that helped sink the Copenhagen meetings.

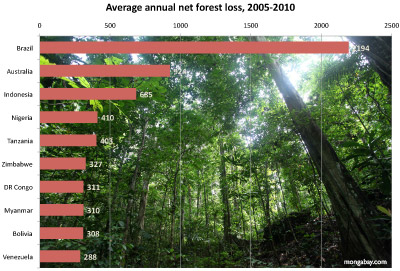

Strangler fig in North Sulawesi |

With

US federal climate change legislation out the window, and the viability of the

UNFCCC in doubt, progress on REDD+ has devolved to the state and provincial

scales in developing countries, many of them organized under the Governors’ Forest and Climate Taskforce

(GCF). (Disclaimer, the Tropical Forest Group has been an advisor to the GCF

for the past year). This so-called sub-national level is where REDD action has

some traction. The GCF states and provinces are widely credited with helping

California move aggressively on including reduced emissions from deforestation

into the California climate legislation. And critically, an

earlier decision (4/CP.15) from the Copenhagen talks provided a

clear signal that sub-national REDD efforts could go forward. This helps firm

up a potential legal link between what is happening in California, the progress

states and provinces have made in reducing emissions, and the international

community.

But

there are many hurdles still ahead. First, the California regulations are only

proposed. The California Air Resources Board will vote on the draft rules December

16th, 2010. Second, negotiations in Cancun are clearly stalled

between countries that are OK with Copenhagen Accord and countries that

outright are hostile to the Copenhagen Accord. And REDD+

is where Bolivian President Morales has drawn a clear line in the sand, at

least for now. Third, Europe continues to refuse to allow developing country

forestry credits into its Emission Trading Scheme. Given the collapse of US

climate legislation and the emergence of RED in California, Europe and the

biggest compliance in America (California) could not be on more different paths

forward for international emission reductions cooperation.

Briefing Note on Proposed CA AB 32 Regulations [PDF]

John O. Niles is the director of the Tropical Forest Group.

Related articles

Amazon tribe establishes first indigenous forest carbon fund

(12/04/2010) A half-century ago, Brazil’s Suruí people knew little of the world beyond their cluster of villages – and nothing of the European settlers who dominated their continent. By 2006, that world beyond had engulfed them – a fact their young chief, Almir Narayamoga Suruí, saw all too clearly the first time he logged onto Google Earth.

Stymied by lack of global climate deal, states develop own low carbon accord

(11/17/2010) California and other states launched an international initiative that will work toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning toward a low carbon economy in the absence of a global climate deal.

Chaos and the Accord: Climate Change, Tropical Forests and REDD+ after Copenhagen

(04/06/2010) The Copenhagen Accord, forged at COP15 upended international efforts to confront

climate change. Never before have 115 Heads of State gathered together at one

time, let alone for the singular purpose of crafting a new climate change

agreement. Even though the new Accord is still in intensive care, two things

are already clear. First, we have entered an entirely new world. And second,

tropical forests have the greatest potential to breathe life into the new

agreement.