Facing the worst outbreak of forest fires in three years, cattle ranchers and indigenous tribesmen in the southern Amazon have teamed up to extinguish nearly two dozen blazes over the past three months, offering hope that new alliances between long-time adversaries could help keep deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon on a downward trajectory.

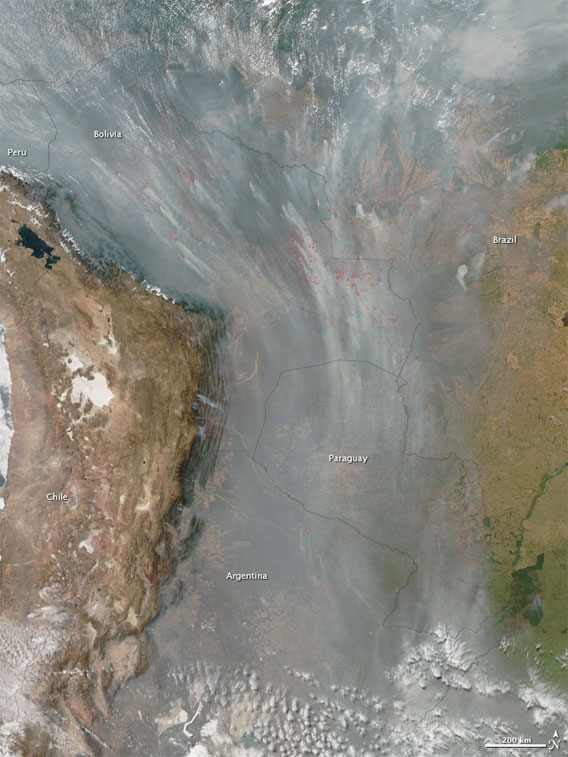

The voluntary fire brigades, which have now spent more than 400 hours battling fires, are the product of partnership between Aliança da Terra, a Brazilian nonprofit working to improve land stewardship by cattle ranchers in the heart of the Amazon; Kayapó and Xavante Indians; local authorities; and the U.S. Forest Service. Over the past two years the Forest Service, with financial assistance from USAID, has led three intensive training sessions on tactics for fighting wild fires. The training came at an opportune time: the number of fires burning in the state of Mato Grosso surged from 5,000 last year to 18,800 this year, the highest since 2007. Exceptionally dry conditions have exacerbated fires set annually for land-clearing. An image released two weeks by NASA shows smoke obscuring a 2,500-kilometer corridor extending from Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil in the north to Argentina in the south. 148,946 fires were burning at the moment the photo was taken.

NASA image courtesy Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Click image to enlarge.

Fire has long been used in the southern Amazon as a way to establish land claims and prepare pasture for low-intensity cattle grazing. But as some ranchers have improved their management practices and in the process, boosted the productivity of their holdings, fire has become an enemy.

Indigenous volunteer firefighter in Mato Grosso.

|

“In Mato Grosso, nobody ever fought against fire,” João Carvalho, administrative manager of Aliança da Terra’s Fire Brigade and the Xavante Project, told mongabay.com. “Non-stop burning was normal.”

But John Cain Carter, the U.S.-born rancher who founded and runs Aliança da Terra, says this has changed. Ranchers are now concerned about losing their investment in maintaining productive pasture. Loss of quality pasture now can leave cattle without fodder until January. In the meantime, cattle will starve without supplemental feed from another source, a costly course of action for an already marginal business. Fire further damages fencing and can wipe out the gardens and farms of small landholders.

Fire also puts forest reserves at risk. Under Brazilian law, landowners are required to maintain 80 percent forest cover on their holdings. Fire—which can spread easily from adjacent pasture lands, especially in years like this one where no rain has fallen since late April—can leave a rancher liable for hefty fines, if local authorities choose to enforce the law.

Once forest is ignited, it extremely difficult to extinguish. Carter says the fire-fighting crews organized by IBAMA, Brazil’s environmental enforcement agency, have often abandoned fires once they have spread into forest areas. The Forest Service-trained brigades on the other hand have fought—and doused—several fires burning in dense forest, include conflagrations said by IBAMA to be “impossible to extinguish.”

All told, Aliança da Terra’s brigade has put out all 22 fires it has faced in pasture, cerrado grasslands, and forest.

The efforts have been assisted by the availability of gear and strategically-placed water tanks funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, a major backer of Aliança da Terra. Several ranchers have also provided gear and financial support. One even contributed a truck.

“This firefighter brigade is now seen as heroes by the farmers, the local population, the squatters and the Indians,” said Aliança da Terra’s Carvalho. “The brigade controlled the fire that would otherwise still be burning.”

Edimar Santos Abreu, a former “squatter” or illegal settler, who now heads up Aliança da Terra’s brigade, said the success in fighting fires marks an important change in the region, where squatters, Indians, ranchers, soy farmers, and land speculators have long been at odds, with conflicts often ending in bloodshed.

“We are all in the fight together,” he told mongabay.com in Portuguese.

The benefits of working together to fight fires extend well beyond protecting against financial losses. Hospitals in the region are presently fully of patients with respiratory problems caused by breathing the choking smoke. Reducing fires will reduce health costs.

The smoke also makes transportation hazardous.

“You don’t want to be in this part of Mato Grosso right now. The smoke is so thick, it’s hard to breathe and dangerous to fly,” said Carter, noting that smoke is less bad in areas where the fire brigades are active.

The success in extinguishing fires also raises an interesting prospect—the emergence of an informal system of governance in region where law enforcement is virtually unknown.

Frank Merry, a scientist at the Moore Foundation, says this development could be the most important outcome of the fire-fighting effort.

“A co-benefit is not only fighting the fires—which, of course, is huge since fire is one of biggest threats to Xingu National Park—but the establishment of frontier governance,” he told mongabay.com. “Having the cowboys and Indians work together sows the seeds of governance and suggests a breaking down of some of the cultural barriers between the frontier groups who have been traditional enemies.”

“To me this is a really interesting entrance to frontier governance outside rule of law,” he continued. “It is a form of self-generated governance.”

The brigade system is set to expand to 16 counties, including five surrounding the Xingu National Park—Gaúcha do Norte, Querência, São Felix do Araguaia, São Jose do Xingu, and Santa Cruz do Xingu—which have nearly 13 million hectares of tropical forests. Members of the current brigades will become trainers of tribes and private landholders once the dry season ends. Aliança da Terra will train “non-Indian” groups, while Colonel Mariano of Mato Grosso’s Corpo de Bombeiros will coordinate indigenous training. Both groups will work in tandem: Indians helping out on private property as well as in the park and the ranchers, farmers, and settlers doing the same. All groups will be connected by radio, according to Carter, who says the program may be adopted state-wide.

Click to enlarge |

“People are fed up with the yearly fires. They are ready for the inferno to end.”

Carter believes the fire-fighting effort could help increase participation in Aliança da Terra’s cadastro or land registry system, which it hopes will eventually create a path for ranchers to sell certified ‘deforestation-free’ beef at a premium or qualify for other benefits, like cheaper loans or better access to markets. To be a member of Alianca’s system, a landowner must meet certain criteria including reporting and monitoring requirements; implementing “no burn” management practices; protecting riparian zones; maintaining forest reserves as specified, but usually unforced, under Brazilian law; and establishing a 10-m wide fire guard between forest and pasture to prevent fires from “escaping” into forest areas. These measures could someday help transform the Brazilian cattle industry from one of the biggest drivers of deforestation to a key partner in saving the Amazon.

Related articles

Jump in fires in Brazil becomes Twitter sensation

(08/27/2010) The number of fires burning in Brazil more than doubled since last year, sparking a Twitter sensation, with more than 120,000 users tweeting messages with the hashtag ‘#chegadequeimadas’ about the fires in a 48 hour window.

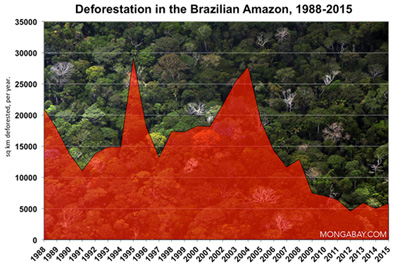

As Amazon deforestation rates fall, fires increase

(06/03/2010) While rates of forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon have been on the decline since 2004, the incidence of fire is increasing in the region, undermining some of the carbon emissions savings of reduced deforestation rates, report researchers writing in the journal Science. The paper argues that REDD, a global plan to reduce deforestation and forest degradation, must include measures to eliminate the use of fire from land management in the Amazon.

Concerns over deforestation may drive new approach to cattle ranching in the Amazon

(09/08/2009) While you’re browsing the mall for running shoes, the Amazon rainforest is probably the farthest thing from your mind. Perhaps it shouldn’t be. The globalization of commodity supply chains has created links between consumer products and distant ecosystems like the Amazon. Shoes sold in downtown Manhattan may have been assembled in Vietnam using leather supplied from a Brazilian processor that subcontracted to a rancher in the Amazon. But while demand for these products is currently driving environmental degradation, this connection may also hold the key to slowing the destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest.

Beef consumption fuels rainforest destruction

(02/16/2009) Nearly 80 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon results from cattle ranching, according to a new report by Greenpeace. The finding confirms what Amazon researchers have long known – that Brazil’s rise to become the world’s largest exporter of beef has come at the expense of Earth’s biggest rainforest. More than 38,600 square miles has been cleared for pasture since 1996, bringing the total area occupied by cattle ranches in the Brazilian Amazon to 214,000 square miles, an area larger than France. The legal Amazon, an region consisting of rainforests and a biologically-rich grassland known as cerrado, is now home to more than 80 million head of cattle. For comparison, the entire U.S. herd was 96 million in 2008.

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon?

(06/06/2007) John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Alianca da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Alianca’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(06/03/2007) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.