Greenpeace finds striking success in targeting big business.

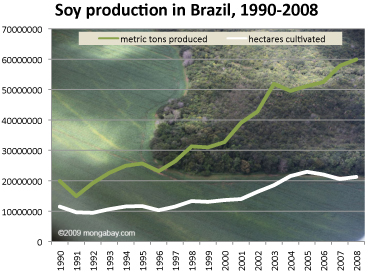

Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation.

A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.

Amazon soy

|

Of the three campaigns, the one targeting the Amazon soy industry—launched in 2006—was the first to show results. That campaign targeted animal feed used to fatten chickens used by major fast food chains, the most notable of which was McDonalds in Europe. Greenpeace spent a year tracking soy as it moved through the supply chain from farms in the southern Amazon to ports on the Amazon River, across the Atlantic, and eventually to poultry facilities in Britain and Ireland.

The response was immediate. McDonalds—stung by the McLibel case of the 1990s and other activist campaigns—immediately demanded its suppliers provide deforestation-free soy, presenting the industry was presented with a daunting dilemma: move towards environmental respectability or of its biggest, and most influential, customers. The largest soy players—whose vast portfolio of commodities are sold globally—chose the former, agreeing to a moratorium on soy grown on newly deforested lands that has changed the way commodities are produced in the Amazon. The moratorium has been extended every year since and through monitoring, which has has continually improved, has shown to be effective at reducing direct forest clearing for soy production.

Palm oil

|

|

With palm oil, the process has been slower, but the impact has been substantial. Since 2008 Greenpeace has released a series of reports linking deforestation in Malaysia and Indonesia to various consumer products giants including Unilever, Nestle, and Cadbury. The reports have been accompanied with colorful campaigns—often featuring activists dressed as orangutans—to highlight the role consumers are playing in destruction of forest habitats by purchasing products containing palm oil from unsustainably managed sources. In the aftermath of the campaigns, all three companies have unveiled new palm oil sourcing policies. The companies’ actions—and new policies—may eventually influence the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, a certification system for the industry.

Amazon cattle

Greenpeace’s biggest success may have come with a 2009 report on cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon. Cattle ranching is overwhelmingly the biggest driver of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: the fate of nearly 80 percent of cleared rainforest land is to serve as forage for livestock. Since 2006 more than 38,600 square miles has been cleared for pasture, bringing the total area occupied by cattle ranches in the Brazilian Amazon to 214,000 square miles, a landscape larger than France. The Brazilian Amazon, region consisting of rainforests and a biologically rich wooded grassland known as cerrado, is now home to more than 80 million head of cattle, up from 26.6 million in 1990 and equivalent to more than 85 percent of the total U.S. herd. Brazil is today the world’s largest exporter and producer of beef.

|

Brazilian cattle products end up in a wide array of consumer goods. Fresh beef is converted into burgers sold in fast-food restaurants and grocery stores across Brazil, Russia, Venezuela, and a number of other countries. Processed meat finds its way into canned products in Europe and America, while leather goes to China, Italy, Vietnam, and Hong Kong. But as Brazil’s beef industry has grown along with its ties to global conglomerates, so has its vulnerability.

The role of the cattle industry in deforestation is no secret. Environmental groups issued reports for years warning that cattle production is the dominant driver of forest destruction, but their campaigns have had no discernible impact on deforestation. Forest clearing remained stubbornly high while beef production continued to expand, enabling the industry to become an economic and political juggernaut, seemingly unstoppable. But in catering toward conglomerates serving an international market producers left themselves exposed to consumer backlash. It’s tough for an environment group to target a subsistence farmer who’s clearing land to feed his family; it’s much easier to go after a multinational enterprise bent on maximizing profits by minimizing raw material costs. Thus in its strength, the multibillion dollar Brazilian cattle industry developed an Achilles’ heel—it was only a clever campaign away from facing this new reality.

In June 2009 Greenpeace leveraged this vulnerability. The green group issued Slaughtering the Amazon [PDF], a report that linked some of the world’s most prominent brands to illegal destruction of the Amazon rainforest. The fallout was immediate and substantial.

Download: Slaughtering the Amazon |

Days after the report was released, Brazil’s biggest domestic beef buyers, supermarket chains Walmart, Carrefour, and Pão de Açúcar, announced they would suspend contracts with suppliers found to be involved in Amazon deforestation. Bertin, the world’s second largest beef exporter, saw its $90 million loan from the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation withdrawn. Investigators raided the offices of JBS, the world’s largest beef processor, and other firms, arresting executives for corruption, fraud, and collusion. And a Brazilian federal prosecutor filed a billion-dollar law suit against the cattle industry for environmental damage, warning that firms found to be marketing tainted meat will be subject to fines of 500 reais ($260) per kilo. BNDES, the development bank that accounts for most financing for the agricultural sector in Brazil, announced it would reform its lending policies, making loans contingent on environmental performance. The cattle industry in the Brazilian Amazon was brought to a virtual standstill, leading major meatpackers and traders to agree to a moratorium—modeled on the 2006 soy moratorium—on deforestation. The industry is now engaged in efforts to develop credible land registries to ensure that beef and leather in the Amazon is no longer produced at the expense of primary rainforests.

Pulp and Paper

Fresh off its success in the Amazon, Greenpeace has returned its focus to Southeast Asia, continuing its campaigns against destructive palm oil producers and launching a new effort against Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a logging company long criticized by green groups for its environmental transgressions. Greenpeace released a report, titled ‘How Sinar Mas is Pulping the Planet’ [PDF] earlier this month alleging that APP—a subsidiary of the Singapore-listed conglomerate Sinar Mas—is destroying carbon-rich peatlands and rainforests. The report once again names major consumer products companies in the United States linked to the firm.

In a July interview with mongabay.com, Rolf Skar, senior forest campaigner with Greenpeace, touches on these campaigns and discusses Greenpeace’s philosophy and approaches to target some of the planet’s biggest and most powerful companies.

AN INTERVIEW WITH ROLF SKAR

Rolf Skar: What is you background and how did you come to work with Greenpeace?

Rolf Skar |

Rolf Skar: I have more than a decade of experience working on forest conservation. Those efforts included work on forests in southern Oregon in the Western United States where the Bush administration focused much of its attempts to dismantle protections for old-growth forest reserves, roadless wildlands, and endangered species on federal lands. Greenpeace got involved in the effort to counter the Bush administration’s logging plans in the area and I had the opportunity to work with Greenpeace staff. A few years later, I joined the organization as a senior forest campaigner.

Q: Greenpeace is a bit unusual among NGOs in that it does not accept corporate contributions. How does this reflect Greenpeace’s culture? How does this affect your fundraising approaches?

Rolf Skar: Greenpeace does not accept contributions from corporations or governments. Maintaining financial independence from political and commercial interests is a key part of the Greenpeace identity and critical to our work. This independence allows us to align our campaign with core values and science rather than political expediency and external influences. For campaigners like me, it means freedom to make decisions without conflicts of interest bind many NGOs. With regard to fundraising, it means depending much more on individual donors. These donations, while more difficult in some ways to garner, are more robust and more resilient. While many NGOs dependent on corporate contributions were forced to cut programs and staff in the last two years, Greenpeace remained largely unscathed by the downturn in financial markets. These individual contributions also grow our grassroots power. After all, our supporters are not just sources of money – they are real people who are ready to make difference.

mongabay: How is Greenpeace structured internationally and how does this affect campaigns? Does Greenpeace strive for unified global messaging?

Forest clearing in Mato Grosso. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Rolf Skar: While Greenpeace spans across the globe, our national and regional offices are closely coordinate with each other and Greenpeace International headquartered in the Netherlands. For cultural reasons, messaging must vary at times from place to place, but our priorities and campaign targets are largely unified. That is a key to our power, and part of what distinguishes us from other environmental NGOs. As drivers of environmental destruction become increasingly global, it is critical we make our work as globally integrated as possible.

mongabay: Over the past 20-30 years, the world has seen a shift in the main drivers of deforestation from poverty (i.e. subsistence farming, government-sponsored rural development/colonization programs and fuelwood production) to trade and consumption, which are primarily the function of consumer demand being fulfilled by corporations. Does Greenpeace see this shift as a prime opportunity to combat deforestation?

Draining and clearing of peat forest in Central Kalimantan (May 2009). Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Rolf Skar: As international trade “flattens” the world, the the shift provides opportunities to organize and target the primary drivers of deforestation. We’ve been doing this with some success in in Indonesia, starting first with big name brand targets and now pressuring the government. The result is the new 2-year moratorium.

mongabay: Greenpeace has been accused of “never letting the facts get in the way of a good story” but in recent years the organization’s reports seem to have put a lot of resources into carefully documenting corporate transgressions via supply chain investigation and GIS-work. Does this mark a conscious decision by Greenpeace to focus on getting the details right and letting the facts speak for themselves?

Rolf Skar: Those targeted by Greenpeace critiques have never been happy with the media attention we focus on them. And, those companies, governments and individuals have always tried to question our credibility to avoid dealing with the important issues we raise. Greenpeace does not have the money or resources of those who destroy the Earth, so we need to be smarter than them. Empty claims would quickly erode our reputation and organizational effectiveness.

mongabay: Do you see danger in “blackwashing” or overstating the environmental transgressions of an industry or company? Can this do long-term damage to a cause or is it a necessary part of influencing the public?

Burning Up Borneo |

Rolf Skar: We need to be accurate in everything we do. It is not in our interest to overstate the impact of an industry or company, because that can erode our credibility. That said, Greenpeace is not afraid to single out companies or to make strong statements in order to be heard in the crowded stage of contemporary media markets. Beyond bold banner slogans, Greenpeace backs up our positions with careful research and on-the-ground knowledge. Most people will never read our reports or take time to understand the details behind our claims. So, we try to strike a balance between the two, especially in the press.

mongabay: How does Greenpeace decide what corporations it targets in its campaigns?

Rolf Skar: There is no universal formula, but we often start by looking at what the problem is, who is driving the problem and who is able to do something about it.

mongabay: From your perspective, what have been the most influential Greenpeace campaigns in recent years?

Rolf Skar: There have been a number of highly successful campaigns, but the one that stands out in my mind is our Amazon campaign. That campaign is one that has truly influenced the playing field, pioneered innovative solutions, and achieved material results.

mongabay: Following a campaign, does Greenpeace advise corporations or industries on how they can reduce their environmental impact?

Rainforest in Borneo (April 2008). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Rolf Skar: Yes. In many ways, the “resolution” of a campaign is just the beginning of our work to address environmental issues with a company. Sometimes we maintain a hands-on, working relationship with companies to develop market and political solutions. Other times we serve largely a watchdog role, monitoring progress and exposing problems with implementation. When it comes to corporations and governments, we have no permanent enemies or friends. So, if a company violates the substance or spirit of an agreement with us, we are prepared to return to active campaign against that company. Likewise, if a long recalcitrant company decides to change its ways, we are happy to work with them. This comes as a surprise to many companies who write us off as unreasonable zealots!

mongabay: Major companies and industries have certainly responded to Greenpeace campaigns, but what about consumers? Is there a danger that consumer apathy could lead multinationals to abandon efforts to clean up their operations?

Rolf Skar: In most cases, companies make environmental commitments because they believe customers either (a) currently demand it or (b) will demand it in the near future. While one could argue attitudes are not shifting fast enough, I think it is clear the momentum is moving towards greater environmental consciousness, not less. Tragedies like oil spills and extinctions – which are growing in magnitude and frequency – are another bulwark against a reversal of this trend.

Sumatra. Photo by Rhett Butler. |

mongabay: How can consumer apathy be addressed? How does Greenpeace compel consumers?

Rolf Skar: People find themselves increasingly distracted and overwhelmed by the details of everyday life. In addition, people have become largely disconnected from sources of the products they buy as supply chains grow longer and more complicated in the global economy. We find that when people have an opportunity to learn about issues related to the products and services they purchase, they are often interested and motivated to do something about it. Greenpeace tried to make things straight-forward and relevant to people by talking about products and brands they are familiar with, then giving them ways to take action. We deliberately try to empower people in a world that seems to be encouraging us all be passive “consumers.”

mongabay: Greenpeace often provokes sharp reactions, but usually from industries and companies that are engaged in damaging practices or individuals who believe environmental problems are overstated. Looking at the other end of the spectrum, how does Greenpeace respond to criticism from environmental groups who say it aren’t doing enough in some areas, for example with timber certification? Some activists say the FSC’s lack of effective safeguards have effectively turned the certification scheme into a greenwashing exercise, while others maintain that now, more than ever, is the time to improve the FSC’s performance. What is Greenpeace’s take?

Rolf Skar: The environmental movement is not monolithic. I believe internal and external differences of opinions and debate is important. When criticized, Greenpeace genuinely tries to learn from the critique, and respond in as transparent and forthright a manner as possible. With regard to certification schemes like the FSC, we are far from naïve about their limitations and problems. Many of the criticisms we hear are totally valid. That is why we do not endorse most certification schemes and why our support for more reputable schemes like the FSC is qualified; we do not support the FSC in all forests or in every situation. When these sorts of debates enter the public sphere, the nuances in our positions are not always properly understood or acknowledged.

Pastureland and transition forest in Mato Grosso, Brazil (April 2009). Since 2003 Brazil has set aside 523,592 square kilometers of protected areas, accounting for 74 percent of the total land area protected worldwide during that period. Photo by Rhett Butler. |

Life on Earth is in big trouble. I think the frustration and sadness that come from this fact can lead some to insist on a more radical or ideological approach. This is a perfectly rational reaction to the environmental destruction going on around the globe. However, an ideologically “pure” approach, while appealing in many ways, can sometimes backfire in practice in an imperfect world. In practice, because of the nature of the problems the Earth faces, we are rarely faced with options that are ideal. In addition, we are confronted, on a daily basis, by the limitations of our own power. There are systemic problems that we are unable to change (at least in the short term) that keep progress partial and victories often incomplete.

Greenpeace has made many mistakes over the years. But we also have a long history of getting real things done, saving real places and holding corporations and governments accountable for environmental crimes. I am confident that track record will continue in the future.

mongabay: The logging, pulp and paper, palm oil, cattle, and soy industries have experienced the wrath of Greenpeace campaigns in recent years — are there any other forest-destroying industries that should be put on notice?

Forest conversion for soy in the Amazon. Photo courtesy of Greenpeace. |

Rolf Skar: There is a long list of industries responsible for deforestation. Illegal logging, paper, palm oil, cattle and soy have simply been leading drivers of forest destruction in recent years. We do not set out to target industries. Rather, we seek to achieve environmental goals, such as zero deforestation in the tropics. So, for example, if coal mining becomes a larger threat to rainforests in Southeast Asia, we will anticipate that and respond appropriately. Likewise, as the threat from dams, roads and pig-iron production grows in the Amazon, we will be paying more attention to the companies and political figures responsible for them.

RELATED

KFC, Walmart contributing to destruction of Indonesia’s rainforests, endangering orangutans

(07/05/2010) Major U.S. companies are contributing to the destruction of Indonesia’s rainforests by sourcing paper from Asia Pulp and Paper (APP), a subsidiary of Indonesia-based conglomerate Sinar Mas, alleges a new report from Greenpeace. Investigating two sites on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, the activist group documented destruction of rainforests and carbon-dense peatlands by APP, a company that has lost several major contacts in recent years due to its poor environmental record. Greenpeace called out Walmart, Auchan, and Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) as companies that continue to buy from APP despite its role in deforestation and peatlands degradation.

(06/02/2010) Radical, controversial, ahead-of-his-time, brilliant, or extremist: call Dr. Glen Barry, the head of Ecological Internet, what you will, but there is no question that his environmental advocacy group has achieved major successes in the past years, even if many of these are below the radar of big conservation groups and mainstream media. “We tend to be a little different than many organizations in that we do take a deep ecology, or biocentric approach,” Barry says of the organization he heads. “[Ecological Internet] is very, very concerned about the state of the planet. It is my analysis that we have passed the carrying capacity of the Earth, that in several matters we have crossed different ecosystem tipping points or are near doing so. And we really act with more urgency, and more ecological science, than I think the average campaign organization.”

Timber certification is not enough to save rainforests

(06/02/2010) In the 1980s and 1990s pressure from activist groups led some of the world’s largest forestry products companies and retailers to join forces with environmentalists to form the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a certification standard that aims to reduce the environmental impact of wood and paper production on natural forests. Despite initial skepticism on whether buyers would pay a premium for greener forest products, FSC quickly grew and by 2000 had become a standard in many markets, including Europe and the United States. Companies like Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Ikea are today strong supporters of the FSC. But the FSC has not been without controversy. In recent years some activists have voiced concern about FSC standards as well as the credibility of auditors that certify timber operations. Among the initiative’s supporters is the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), a group best known for its aggressive protest tactics. RAN says engagement with the FSC is better than the alternative: leaving the timber industry to devise its own sustainability standards.