Trusts and foundations face difficult choices on how to invest in forest protection.

If your organization receives grants from trusts and foundations, chances are you’ll be asked to prove the money is spent effectively. Grant evaluation forms are crisscrossed with language on outputs, outcomes and impacts. But who is asking the philanthropists how effectively they give money away in the first place?

Although environmental causes attract only a tiny percentage of overall philanthropic spend, individual grant-making foundations invest substantial sums in rainforest protection. Many philanthropists rate themselves as agents of change, boldly shifting the dial on issues that other sources of funding cannot reach. Philanthropic capital can tackle issues that are too hot for governments and too unprofitable for business, at least as the theory goes.

In short, philanthropy has potential to catalyze change that would otherwise not happen. This is a tall order for any funder, particularly those working on complex problems like tropical deforestation, where a number of different approaches compete for support.

As yet, there are few attempts to measure whether the practice of forests philanthropy lives up to its potential. Are grantmaking foundations investing their millions strategically or not?

Rainforest of the Darien, Colombia (2010). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

‘Saving the Rainforests’, a new report for the UK Environmental Funders Network (EFN) lays out various pathways to reducing deforestation, including carbon payments, the reform of commodity supply chains, and the expansion of protected areas, along with the ways in which civil society groups are treading these paths. In doing so, the mapping helps funders relate their grantmaking to the broader civil society effort.

Big questions for forest philanthropists include whether the balance of their investments is about right, whether there are gaps in need of filling, or equally areas of high capacity in less need of support.

Positive feedback on the mapping report suggests that foundation staff are lacking frameworks for asking these questions. Indeed, one commentator suggests that trusts are “perplexed” about where precisely the challenges and opportunities lie for reducing global forest loss.

Furthermore, funders must navigate fault-lines that have opened up within civil society regards forest protection. Witness the hostility between groups that advocate and oppose the trading of forest carbon offsets. Or the ideological differences between groups that believe the pathway to forest protection lies through either cooperation or confrontation with business.

Such divisions complicate the picture for grantmakers, who are courted by a diversity of would-be grantees presenting different visions of change and different plans for getting there. All of these are valid in their own way. So how can grantmakers choose which to prioritize?

A good place to begin is with a better understanding of how resources are allocated between different approaches now.

To complement ‘Saving The Rainforests’, we collected income data for 52 of the civil society groups featured in the report, in order to explore the resource base associated with the nine ‘storylines’ defined in the report.

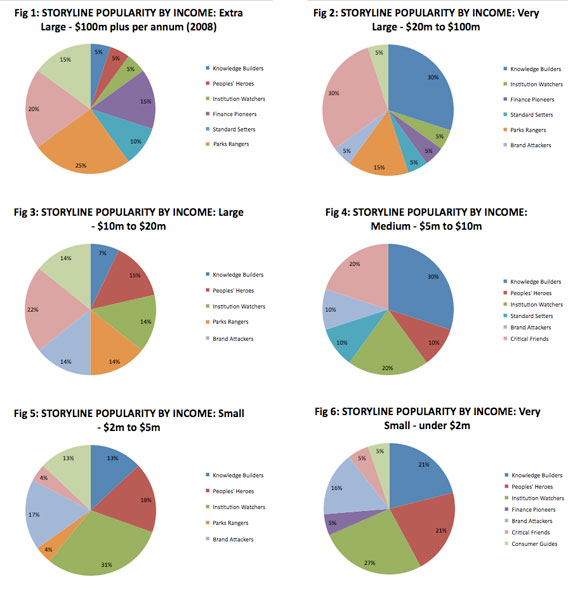

These storylines relate to different organizational roles within the forests movement. For instance, there are ‘Institution Watchers’, groups that monitor the integrity of forest governance, ‘Peoples Heroes’, which hail from a strongly rights-led perspective, and ‘Parks Rangers’ that carry out practical forest management. Individual groups were assigned to a maximum of three storylines at once.

The groups were grouped into six income categories, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Income base associated with profiled forest CSOs

|

At nearly $1.4 billion, The Nature Conservancy had far and away the largest 2008 revenues of any group, nearly six times the size of the second largest group, Conservation International. Excluding TNC, the average income across the 51 remaining groups was $34.2 million. This average reflects a small number of groups with very large incomes. The median income was just $8.3 million and 25 groups had an income smaller than this.

Although the figures do not represent the resource base associated specifically with forests programs, they do reveal a relationship between organizational size and the popularity of certain storylines.

For example, 20 percent of storyline counts recorded for organizations with incomes of $5m or more are as ‘Critical Friends’ – groups that work collaboratively with business. This figure shrinks to five percent or less for organizations in income categories less than $5m.

The prevalence of ‘Brand Attackers’ – groups that expose and attack poor corporate practice – follows a near mirror-image pattern. This storyline scores well among organizations with incomes of less than $5m, and decreases in popularity as income rises.

The proportion of ‘Institution Watchers’ and ‘Peoples Heroes’ also increases as organizational income decreases. The ‘Parks Rangers’ storyline works the other way, with larger organizations more likely to undertake practical conservation work.

One major storyline that appears relatively independent of income is ‘Knowledge Builders’ – engaging in applied research seems popular across the board.

Why is this relevant to grantmakers? Most powerfully, it is a reminder that the process of social and political change is not one of equal opportunities. Some approaches benefit from a much larger resource base than others.

Corporations or governments, in particular, are more likely to sponsor organizations that choose the carrot over the stick in terms of stakeholder engagement. Thus it isn’t surprising to see that the average ‘Peoples Hero’, ‘Brand Attacker’ or ‘Institution Watcher’ is a smaller organization than the average ‘Critical Friend’ or ‘Parks Ranger’.

It is true that some storylines are more capital-intensive than others. Managing protected areas, for instance, typically involves greater expense than monitoring an institution like the World Bank. And money may not be the only limiting factor. Intellectual and political capital may also be in short supply.

Effective philanthropy requires grantmakers to think about where they can add most value. Foundations are in the privileged position of being able to support radical or disruptive demands for change. Indeed a poll of nearly 1,000 UK philanthropy experts identified “campaigning which led to major social change” among the field’s defining achievements.

It may be that smaller forests organizations come up the pecking order if we consider the distribution of philanthropic grants as distinct from total revenues, which comprises government, corporate and membership income as well.

But analysis of the UK environmental movement suggests philanthropic capital too tends to ‘follow the money’, accruing to small numbers of large green groups. For instance, the top 100 recipients of green grants between 2003 and 2007 secured over 60 percent of total grants by value, although numbering only 5 percent of all grantees. Whether or not similar patterns hold true in forests philanthropy has not yet been explored.

There is no perfect formula for the allocation of funding across civil society – where donors think the balance should lie ultimately depends on their own value systems and theories of change. More frank, well-informed discussion of these points would benefit everyone. As well as asking grantees to prove their worth, forests funders would do well to turn the question of ‘effectiveness’ back upon themselves.

Harriet Williams helps coordinate the UK Environmental Funders Network. This piece is written in a personal capacity, and does not necessarily represent the view of the network.