The tiger has an estimated population of 3,400-5,000 individuals; the giant panda, 1,000-2,000; the North Atlantic right whale, 350-400; the Sumatran rhino, 250; and the California condor, 170. A new study shows that none of these species is safe from extinction yet, although each has received considerable conservation attention compared to most imperiled species.

The study published in Biological Conservation found that conservationists are targeting minimum numbers of population that are far too small to guarantee safety for a species in light of continued environmental upheaval, including climate change and habitat loss.

“Conservation biologists routinely underestimate or ignore the number of animals or plants required to prevent extinction,” says lead author Dr Lochran Traill, from the University of Adelaide’s Environment Institute.

The common figure used for conservation efforts is known as the ’50/500 rule’. According to this idea, a species needs fifty adults to ensure the species isn’t inbreeding and 500 individuals to avoid extinction due to environmental change.

“Our research suggests that the 50/500 rule is at least an order of magnitude too small to effectively stave off extinction,” says Traill. “Often, [conservationists] aim to maintain tens or hundreds of individuals, when thousands are actually needed. Our review found that populations smaller than about 5000 had unacceptably high extinction rates. This suggests that many targets for conservation recovery are simply too small to do much good in the long run.”

However, Traill adds that the research in no way suggests that species with populations under 5,000 are beyond help. This is borne out by history: the white rhino went from around 20 individuals to being the most populous rhino in the world with over 17,000 recorded in 2007, and the Wisent, or European bison, went from only 12 individuals to well over 1,000 wild animals.

However, the research does “highlight the challenge that small populations face in adapting to a rapidly changing world”, says Traill. He recommends that conservation organizations make changes to target saving thousands rather than hundreds of individuals.

“The conservation management bar needs to be a lot higher,” says Dr Traill. “However, we shouldn’t necessarily give up on critically endangered species numbering a few hundred of individuals in the wild. Acceptance that more needs to be done if we are to stop ‘managing for extinction’ should force decision makers to be more explicit about what they are aiming for, and what they are willing to trade off, when allocating conservation funds.”

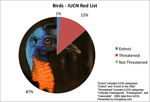

Many biologists believe that the world is currently undergoing a mass extinction. According to the latest figures from the IUCN Red List, 12 percent of birds, 21 percent of mammals, 30 percent of amphibians, 31 percent of reptiles, and 37 percent of fish are threatened with extinction. However many believe even these high figures are underestimations, since only 2.7 percent of described species have been assessed by the IUCN. Unlike the tiger, the giant panda, the Sumatran rhino, the North Atlantic right whale, and the California condor, most species still linger in conservation obscurity.

Related articles

Extinction debt can last millions of years

(07/29/2009) Extinction can be set in motion millions of years before a species’ actual demise, suggesting that present-day drivers of habitat destruction and degradation may have already doomed many species to eventual extinction, report researchers writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society B online.

869 species extinct, 17,000 threatened with extinction

(07/02/2009) Nearly 17,000 plant and animal species are known to be threatened with extinction, while more than 800 have disappeared over the past 500 years, reports the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). While these numbers are substantial, they are likely “gross” underestimates since only 2.7 percent of 1.8 million described species have been assessed. The IUCN report warns that governments will miss their 2010 target for reducing biodiversity loss.

Over 30 percent of open ocean sharks and rays face extinction

(06/25/2009) The first global study of open ocean (pelagic) sharks and rays found that 32 percent of the species are threatened with extinction largely due to overfishing and bycatch, making pelagic sharks and rays more threatened than birds (12 percent), mammals (20 percent), and even amphibians (31 percent), which are considered to be undergoing an extinction crisis. The situation worsens when only sharks taken in high-seas fisheries are considered: 52 percent of these species are threatened.