Why do different species of bird lay different numbers of eggs?

mongabay.com

December 10, 2008

Climate proves to be on the determining factors say scientists

Clutch size varies greatly between bird species. Researchers now have a better idea why.

Analyzing data on clutch size, biology, and habitat for 5,290 species of birds, a team of biologists — Walter Jetz (UC San Diego), Cagan H. Sekercioglu (Stanford University), and Katrin Böhning-Gaese (Johannes Gutenberg-Universität) — developed a model to predict variations in the number of eggs a species lays. They found clutch sizes are consistently largest in cavity nesters and in species occupying seasonal environments. The findings add depth and complexity to previous research that has shown short-lived species — ones that face high predation or have low survival rates among offspring — tend to lay more eggs than longer-lived species, which invest more resources in raising their offspring.

Eggs in a Great Tinamou Nest. Photo by Dr. Çağan H. Şekercioğlu |

"With this approach, we were able to explain a major proportion of the global variation in clutch size and also to predict with high confidence the average clutch size for types of birds living and breeding in certain environments," said Walter Jetz, an associate professor of biology at UC San Diego and the senior author of the study. "For example, cavity nesters, such as woodpeckers, have larger clutches than open-nesting species. And species in seasonal environments, especially those living at northern latitudes, have larger clutches than tropical birds.

"In this study we answer one of the most basic questions asked about birds: Why do bird species lay different numbers of eggs?," added Cagan Sekercioglu, a senior research scientist at Stanford University. "The integration of geographic and life history datasets enabled us to simultaneously address the importance of ecological, evolutionary, behavioral and environmental variables in shaping the clutch size of world's birds. We show that increased environmental variation causes birds to lay larger clutches."

Pauraque nest eggs. Photo by Dr. Çağan H. Şekercioğlu |

"Most ornithological research has taken place in the highly seasonal environments of North America and Europe, but most bird species live in less seasonal tropics," he continued. "Therefore, the small clutch size seen in less-studied tropical birds is the norm, not the exception. Increased predation pressure experienced by open-nesting birds also causes them to lay smaller clutches than cavity-nesting birds, literally having fewer eggs in one basket to spread the risk."

The researchers say the findings may help conservationists assess risks to threatened species and devise strategies for their protection, especially in the face of climate change.

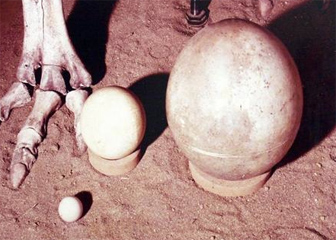

The egg of the extinct Elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus), a species once native to Madagascar. The egg on the far left is a chicken egg, while the one in the middle is an ostrich egg. Photo from Berenty, Madagascar. |

"Our results demonstrate not only where bird species live, but how the way they live their lives, specifically their reproduction strategies, has evolved in close association with climate, particularly seasonality," explained Jetz. "Rapid changes to the global geography of climate are likely to impact both aspects and to potentially perturb the long-evolved link between the 'where' of life and the 'way' of life in many species."

"The majority of bird species live in the tropics," added Sekercioglu. "Tropical birds' smaller clutch size is greatly shaped by more stable climates and these birds' survival depends on the continuity of the weather conditions they have adapted to during millennia. Climate change and a potential increase in climatic fluctuations in the tropics may make these birds highly vulnerable. Hundreds of tropical bird species are already threatened with extinction and a potential clash between changing climate and their reproductive strategies may cause additional harm."

CITATION: Walter Jetz, Cagan H. Sekercioglu, and Katrin Böhning-Gaese. The Worldwide Variation in Avian Clutch Size across Species and Space. PLoS Biol 6(12): e303 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060303

Related articles

Birds face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought

An interview with ornithologist Dr. Cagan Sekercioglu

July 15, 2008

Birds may face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought, says a bird ecology and conservation expert from Stanford University. Dr. Cagan H. Sekercioglu, a senior research scientist at Stanford and head of the world’s largest tropical bird radio tracking project, estimates that 15 percent of world’s 10,000 bird species will go extinct or be committed to extinction by 2100 if necessary conservation measures are not taken.

Sedentary, not migratory birds, face higher extinction risk June 24, 2007

Sedentary birds face considerably higher risk of extinction than migratory birds, reports a new paper published in the journal Current Biology. The findings have implications for the conservation of increasingly endangered wildlife populations.