Armageddon for amphibians? Frog-killing disease jumps Panama Canal

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

October 12, 2008

Chytridiomycosis — a fungal disease that is wiping out amphibians around the world — has jumped across the Panama Canal, report scientists writing in the journal EcoHealth. The news is a worrying development for Panama’s rich biodiversity of amphibians east of the canal.

Chytridiomycosis is caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a fungal pathogen that has been implicated in the extinction of more than 100 species of frogs and toads since the early 1980s. While scientists don’t yet know the origin of the fungus, they suspect it might be the African clawed frog, a species that has been shipped around the world for research purposes. The fungus is highly transmissible and has spread to at least four continents, in some cases probably introduced unintentionally by humans in the treads of their shoes. As it spreads, the disease lays waste to more than 80 percent of amphibians across a wide range of habitats, including those that are undisturbed by humans. Some researchers have suggested that climate change could be creating conditions that exacerbate the impact of the pathogen — which predominantly affects highland species — although the theory is still controversial.

Panama golden frogs mating in captivity. Photo by Rhett A. Butler Panama’s golden frog (Atelopus zetecki), a species that may now be extinct in the wild due to Chytridiomycosis. In many parts of Panama this frog — actually a species of harlequin toad — is considered a good luck charm and was once collected from the wild by people to put in their homes. |

In Panama scientists have been closely monitoring the spread of the pathogen as well as setting up emergency conservation measures to capture wild frogs and safeguard them in captivity until the disease is controlled or at least better understood. Still there has been cautious hope that the Panama Canal would serve as a natural barrier to slow or even stop the spread of Chytrid to eastern Panama, a particularly species-rich region that had so far avoided the decimation seen in western Panama and Costa Rica. Now an international team of researchers report that Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis has been detected in three species east of the Panama Canal at Soberanía National Park. Although the scientists note that the results are preliminary and more work needs to be done to determine the origin and incidence of the Chytridiomycosis in Soberanía, the finding is bad news for Panama’s amphibians.

The Red-eyed tree frog, a species that is often found in lowland areas in Central America, is not particularly at risk from Chytridiomycosis. |

“Our results suggest that Panama’s diverse and not fully described amphibian communities east of the canal are at risk,” the authors write. “Precise predictions of future disease emergence events are not possible until factors underlying disease emergence, such as dispersal, are understood. However, if the fungal pathogen spreads in a pattern consistent with previous disease events in Panama, then detection of Bd at Tortí and other areas east of the Panama Canal is imminent.”

The scientists say that physical barriers to the spread of Chytrid — including salt water, deforested lowlands where high temperatures kill the fungus, and the Panama Canal — are being “easily overcome” in Panama by “human movement of the pathogen”. In other words, human activities like tourism, scientific research, and construction are facilitating the epidemic. The authors suggest that measures to reduce transportation of Chytrid such as “bleaching boots and cleaning field gear between sites, and providing information at eco-lodges” could help contain the disease.

Adding to the gloom for amphibians

|

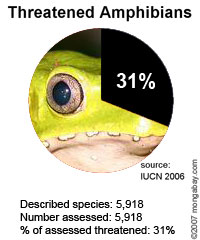

But even the containment of Chytrid might not be enough to save amphibians, which face a barrage of other threats including pollution, the introduction of alien species, habitat destruction, over-collection, and climate change. According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive survey of the world’s 6,000 known species of frogs, toads, salamanders, newts and caecilians, about one-third of amphibians are classified as threatened with extinction. Scientists say the worldwide decline of amphibians is one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group could follow.

In an effort to save the most at-risk species, last year saw the launch of the Amphibian Ark, an initiative by zoos, aquariums, and botanical gardens to establish captive populations for 500 species at about $100,000 per species. Overall the coalition is looking to raise $400 million over 5 years for long-term research, protecting critical habitats, reducing trade in amphibians for food and pets, and establishing captive breeding programs. Amphibian Ark hopes to return rescued species to the wild once Chytrid and other threats have been controlled.

Douglas C. Woodhams at al. (2008) “Chytridiomycosis and Amphibian Population Declines Continue to Spread Eastward in Panama.” EcoHealth DOI: 10.1007/s10393-008-0190-0