Worst mass extinctions occur when temperatures are the warmest

Worst mass extinctions occur when temperatures are the warmest

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

October 24, 2007

Warming temperatures could trigger a mass extinction event’, warn scientists writing in the latest issue of Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Comparing ancient records of marine and terrestrial diversity with historical temperature estimates, researchers from the Universities of York and Leeds found a close correlation between Earth climate and extinctions over the past 520 million years: higher extinction rates occur at higher temperatures.

“We found that over the fossil record as a whole, the higher the temperatures have been, the higher the extinctions have been,” lead author Peter Mayhew, a University of York ecologist, told the Associated Press.

|

Mayhew, together with University of York student Gareth Jenkins and University of Leeds Professor Tim Benton, say that temperatures forecast over the next century are “within the range of the warmest greenhouse phases that are associated with mass extinction events identified in the fossil record.”

“Our results provide the first clear evidence that global climate may explain substantial variation in the fossil record in a simple and consistent manner. If our results hold for current warming – the magnitude of which is comparable with the long-term fluctuations in Earth climate – they suggest that extinctions will increase,” said Mayhew.

The researchers note that four of the five historical mass extinction events are associated with warm greenhouse phases. The largest mass extinction event of all, the end-Permian when 95 percent of animal and plant species disappeared, occurred during one of the warmest-ever climate phases.

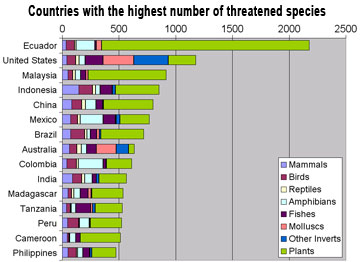

Ecologists have long warned that the human-induced climate warming could trigger a massive die-off of species. Dr. Thomas Lovejoy, a leading biologist who coined the term “biological diversity”, estimate that 10-20 percent of all species could go the way of dinosaurs by the year 2020. Peter Raven, another leading scientists, has predicted that 565 species of mammals and at least 500 species of birds will go extinct within the next 50 years.

CITATION: Peter J. Mayhew, Gareth B. Jenkins, Timothy G. Benton (2007). A long-term association between global temperature and biodiversity, origination and extinction in the fossil record. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Tuesday, October 23, 2007

ABSTRACT: The past relationship between global temperature and levels of biological diversity is of increasing concern due to anthropogenic climate warming. However, no consistent link between these variables has yet been demonstrated. We analysed the fossil record for the last 520Myr against estimates of low latitude sea surface temperature for the same period. We found that global biodiversity (the richness of families and genera) is related to temperature and has been relatively low during warm greenhouse’ phases, while during the same phases extinction and origination rates of taxonomic lineages have been relatively high. These findings are consistent for terrestrial and marine environments and are robust to a number of alternative assumptions and potential biases. Our results provide the first clear evidence that global climate may explain substantial variation in the fossil record in a simple and consistent manner. Our findings may have implications for extinction and biodiversity change under future climate warming. (The Royal Society)

|

Extinction, like climate change, is complicated

(3/26/2007) Extinction is a hotly debated, but poorly understood topic in science. The same goes for climate change. When scientists try to forecast the impact of global change on future biodiversity levels, the results are contentious, to say the least. While some argue that species have managed to survive worse climate change in the past and that current threats to biodiversity are overstated, many biologists say the impacts of climate change and resulting shifts in rainfall, temperature, sea levels, ecosystem composition, and food availability will have significant effects on global species richness.

Global warming may cause biodiversity extinction

(3/21/2007) Extinction is a hotly debated, but poorly understood topic in science. The same goes for climate change. When scientists try to forecast the impact of global change on future biodiversity levels, the results are contentious, to say the least. While some argue that species have managed to survive worse climate change in the past and that current threats to biodiversity are overstated, many biologists say the impacts of climate change and resulting shifts in rainfall, temperature, sea levels, ecosystem composition, and food availability will have significant effects on global species richness.

|

Biodiversity extinction crisis looms says renowned biologist

(3/12/2007) While there is considerable debate over the scale at which biodiversity extinction is occurring, there is little doubt we are presently in an age where species loss is well above the established biological norm. Extinction has certainly occurred in the past, and in fact, it is the fate of all species, but today the rate appears to be at least 100 times the background rate of one species per million per year and may be headed towards a magnitude thousands of times greater. Few people know more about extinction than Dr. Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. He is the author of hundreds of scientific papers and books, and has an encyclopedic list of achievements and accolades from a lifetime of biological research. These make him one of the world’s preeminent biodiversity experts. He is also extremely worried about the present biodiversity crisis, one that has been termed the sixth great extinction.

European blood-sucker falls victim to global warming

(8/26/2007) Europe’s only known land leech may be on the brink of extinction due to shifts in climate, report researchers writing in the journal Naturwissenschaften. The findings are significant because they suggest that “human-induced climate change without apparent habitat destruction can lead to the extinction of populations of cold-adapted species that have a low colonization ability,” according to the authors.

Climate change claims a snail

(8/12/2007) The Aldabra banded snail (Rachistia aldabrae), a rare and poorly known species found only on Aldabra atoll in the Indian Ocean, has apparently gone extinct due to declining rainfall in its niche habitat. While some may question lamenting the loss of a lowly algae-feeding gastropod on some unheard of chain of tropical islands, its unheralded passing is nevertheless important for the simple reason that Rachistia aldabrae may be a pioneer. As climate change increasingly brings local and regional shifts in precipitation and temperature, other species are expected to follow in its path.

|

Just how bad is the biodiversity extinction crisis?

(2/6/2007) In recent years, scientists have warned of a looming biodiversity extinction crisis, one that will rival or exceed the five historic mass extinctions that occurred millions of years ago. Unlike these past extinctions, which were variously the result of catastrophic climate change, extraterrestrial collisions, atmospheric poisoning, and hyperactive volcanism, the current extinction event is one of our own making, fueled mainly by habitat destruction and, to a lesser extent, over-exploitation of certain species. While few scientists doubt species extinction is occurring, the degree to which it will occur in the future has long been subject of debate in conservation literature. Looking solely at species loss resulting from tropical deforestation, some researchers have forecast extinction rates as high as 75 percent. Now a new paper, published in Biotropica, argues that the most dire of these projections may be overstated. Using models that show lower rates of forest loss based on slowing population growth and other factors, Joseph Wright from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and Helene Muller-Landau from the University of Minnesota say that species loss may be more moderate than the commonly cited figures. While some scientists have criticized their work as “overly optimistic,” prominent biologists say that their research has ignited an important discussion and raises fundamental questions about future conservation priorities and research efforts. This could ultimately result in more effective strategies for conserving biological diversity, they say.