Ecotourism works in Costa Rica

True ecological tourism works in Costa Rica:

An interview with author and eco-lodge pioneer Jack Ewing

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

June 12, 2007

In 1970 a young man went to Costa Rica, a place he initially confused with Puerto Rico, on an assignment to accompany 150 head of cattle. 37 years and several lifetimes’ worth of adventures later, Jack Ewing runs a eco-lodge that serves as a model for a country now considered the world leader in nature travel.

Ewing tells his story and dozens more in a new book, Monkeys Are Made of Chocolate. Weaving science, humor, and personal anecdotes into a collection of essays, it quickly becomes evident that Ewing has changed lives and made his made his part of the world a better place.

Monkeys Are Made of Chocolate includes 32 short stories that describe the natural beauty of Costa Rica and its rich diversity of flora and fauna. Daniel Quinn, author of Ishmael, among other works, has contributed the forward to the book, which is a perfect companion for eco-minded travelers and great reading material for adults who want to encourage their children’s interest in science and the world around them.

INTERVIEW WITH JACK EWING

Mongabay: How do you come to own a ranch in Costa Rica?

Monkeys Are Made Of Chocolate: Exotic And Unseen Costa Rica |

Ewing:

My introduction to Costa Rica was in 1970, and my reasons for coming here had nothing to do with rainforest conservation or ecological tourism. At the time I was in the cattle business. Fresh out of the Colorado State University with a degree in animal husbandry, I went to work for my father, but found, as have many other young men, that working with Dad is sometimes difficult or impossible. I ended up managing a cattle farm in Ontario, Canada. As it turned out, I couldn’t get along any better with that employer than I did with my dad. At the time it didn’t occur to me that my own immaturity might be a big part of the problem, but that’s a different story. Regardless of who was right and who was wrong, I decided it was time to look for another job.

The fateful phone call came one night during dinner. “I’m exporting about 150 head of cattle to Costa Rica,” said the voice on the other end of the line, a man named Ken Allen. “We’ll truck them to Miami and fly them on down from there.”

My wife, Diane, and I talked it over and decided to accept the offer. We weren’t happy where we were, and Costa Rica sounded like an interesting experience.

After a nerve-racking flight in a prop plane with 37 cattle down to Costa Rica, followed by four months on Ken’s property, I worked on a big ranch on the Caribbean side of Costa Rica. In 1792 I first visited Hacienda Barú, which the meat packing company had leased for fattening cattle. In 1976 I left the packing company and became a partner with the owners of Hacienda Barú, which, over the next 30 years, was destined to evolve from a cattle ranch into Hacienda Barú National Wildlife Refuge.

Mongabay: What inspired you to let your farmland to go wild?

Ewing: The inspiration to let farmland grow wild, didn’t come as one big revelation. Rather it came in bits and pieces and not all of them were related to the environment. Some were purely economical and others a matter of circumstance.

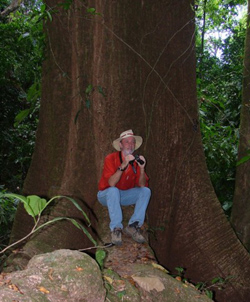

Jack Ewing |

In 1972, I first visited Hacienda Barú because the meat packing company I worked for had leased it to run cattle on. There was a squatter on the land at that time. He had deforested about 20 acres and was growing corn. I convinced the squatter to leave peacefully by paying him the value of his corn crop and promising not to file charges against him. We never harvested the corn — the monkeys got it all — and we never developed the land that the squatter had deforested. It just grew pack naturally. Today it is the oldest secondary forest on Hacienda Barú 35 years old.

In 1979 I had figured out that one of our pastures, located on a steep hill, was costing more to maintain than it was worth. I had heard about reforestation and decided that economically we would be better off to grow trees there rather than spending money to chop weeds and fix fence. I talked to some knowledgeable people, and they convinced me that the hillside was too steep for a conventional tree plantation and recommended that I let the forest come back naturally. I took that advice and the results are impressive. That is the second oldest secondary forest on Hacienda Barú.

Hacienda Baru: before (1972) [above] and after (2005) [below]. Courtesy of Jack Ewing |

The next land to be abandoned to Mother Nature was in 1981. I realized that the wildlife in the mangrove forest — an isolated patch of about 75 acres of forest near the mouth of the Barú River — needed a buffer, as the pasture went right to the edge of the water in the mangrove swamp. I fenced off a strip 50 yards wide and let it grow wild. The wildlife soon spread into that area.

The next area to grow wild was the cacao plantation. That decision was purely economical. In 1985, the price of cocoa on the international market dropped so low that it was no longer profitable or economically feasible to maintain and harvest the plantation. In 1987, we let Mother Nature have it.

All of this time my love of tropical nature was growing and I was thinking more and more about wildlife habitat and biological corridors which help rainforest animals move between forest fragments.

I had six partners in Hacienda Barú. They weren’t interested in tropical nature, and were only speculating on the land, waiting for land values to appreciate. By the late 1980s I was already calling Hacienda Barú a nature reserve. They thought it was funny and made jokes about it. Nevertheless, they didn’t stop me, as what I was doing didn’t really cost much. In 1990 they decided that the time to sell had come, and they put Hacienda Barú on the market. In 1993 a man named Steve Stroud, bought out their share and became partners with me. We both felt the same about conservation and proceeded to let most of Hacienda Barú return to the wild. In 1994 we petitioned the government to declare it a National Wildlife Refuge. In 1995, that status was granted by presidential decree. We kept about 50 acres of pasture for horses, because we were doing horseback tours. In 1996 we discontinued the horseback tours and let that last pasture go back to forest. Today only about 40 acres out of 815 total (less than 5%) is not in natural habitat. This is where we have the lodge and plan to do some residential development.

Mongabay:

Were you surprised at the rate that the land was re-colonized by forest and wildlife?

Ewing:

At first, I kept wanting the jungle to grow back faster. In the tropics vegetation grows fast. If you just quit chopping the weeds, you have a respectable secondary forest before you know it. Thinking back on it, I would have to say that at first I was expecting things to grow faster, but later on — like 10 years later — I was amazed to see the tall secondary forest and think back a few years when it was still a pasture. What did surprise me was how fast the wildlife moved in. Before the secondary growth could even be called a forest, we were seeing things like peccaries, pacas, monkeys, ocelots and margay cats and quite a few other animals. Even the sloths moved in fairly quickly.

Mongabay:

What has been the biggest challenge running Hacienda Barú?

Jack Ewing sitting on the buttress root of a Kapok or Ceiba tree |

Ewing:

My biggest challenge in managing Hacienda Barú has also been my biggest reward. In the late 1980s, when we first began doing a few tours, I made a decision to work exclusively with local people. I saw other tourist businesses start up in the area, and hire people from the cities or even foreigners to do the high paying jobs and give the lowliest jobs to the local people. It seemed to me that if tourism were to be the wave of the future in the region, it had to benefit the people who lived there. The first challenge was convincing uneducated country people that attending to tourists was a good business. People who had been cowboys became tour guides, housewives became receptionists and waitresses, and others became cooks. Certainly the lowest jobs had to be done by someone, but at Hacienda Barú, all of the jobs, from top to bottom, were done by locals. Teaching them English was a real challenge. Some took courses in English, some learned on the computer and others simply picked it up. Not everyone at Hacienda Barú speaks English but the ones that have direct contact with tourists all speak enough to get by. When Hacienda Barú was a cattle ranch, we employed three people, a cowboy, a fence fixer and a weed chopper. Today we employ 33 people. Eight of our nine guides speak English. All three receptionists speak English. My assistant doesn’t have a high school degree, but I wouldn’t trade her for most of the college graduates that I know who have a degree in business administration. She learned how to run Hacienda Barú by doing it. When Hacienda Barú was a cattle ranch only one of the three employees had been able to save enough money to buy a bicycle. Today seven out of the 33 have cars and three have motorcycles. Many of our employees today are the children of parents who worked here when they were born. Seeing this happen has been very gratifying.

Mongabay:

Costa Rica has a particular emphasis on tourism and the environment. Do you believe that projects like Hacienda Barú can be initiated on a broader scale, in other tropical countries?

Three-toed sloth at Hacienda Barú Coatimundi. Photos courtesy of Jack Ewing |

Ewing:

Projects like Hacienda Barú that combine tourism and conservation already exist in many places. The Nature Conservancy recently published a book about private conservation in Costa Rica. Hacienda Barú is featured in the book along with 32 other private conservation initiatives. Many of these rely on ecological tourism to finance the conservation. The conservation work, in turn, enhances the ecological tourism. This type of business may not be as profitable in the short term as mass tourism, but they are much more sustainable and provide a good steady income over a long period of time. There are many ecological tourism destinations in other countries that combine conservation and ecological tourism. Most of them are members of The International Ecotourism Society. If you do something that is successful, others will imitate you.

Every one of these projects is unique and it would be difficult to name a single key to success. However, I would say that being sincere about conservation and ecology and designing your business so that it truly favors the environment is extremely important. Many businesses call themselves ecological without really doing anything ecological. Ecological tourists know the difference and the word soon spreads. I once wrote an article about the difference between true ecological tourism and that which is ecological in name only. I’m not writing this from my own computer, so I can’t send you the article now, but it was titled -Ecological Tourism, More than Green Paint.

Mongabay:

What are the keys to making such projects successful (i.e. economically viable)?

Ewing:

The key to making a project such as Hacienda Barú successful is sincerity. Most of our guests come to us because other guests have recommended us. Ecological tourists who stay at Hacienda Barú are most impressed by our staff, all local Costa Ricans, and their dedication to the environment. They appreciate that we practice what we preach and they tell others about it. This has been the greatest single factor contributing to our success.

Mongabay:

What do you believe is the best way to protect rainforests and their wildlife?

Owls at Hacienda Barú Red dart frog. Photos courtesy of Jack Ewing |

Ewing:

The best way to protect rainforests and their wildlife is to make it profitable to do so. At Hacienda Barú we have done this through ecological tourism. If we didn’t have the income from the tourists who visit us, we would not be able to continue to protect the natural habitats at Hacienda Barú. Other people have made it profitable in other ways. I know of one residential development project where the developers put an environmental easement on the rainforest that covered about half of the 500 acres of land and only built homes in the areas that had previously been used for pasture. Additionally, much of the pasture land was allowed to regenerate into secondary forest. By conserving the large forest and allowing the natural regeneration to take place between home sites, the developer made the entire project more attractive to prospective buyers. The buyers were willing to pay more for a home site surrounded by wildlife habitat and were therefore willing to pay more. These are two examples of making conservation profitable.

Mongabay:

What can we do at home to help save rainforests?

Ewing:

I can think of two ways that people living in the US can help save the rainforest.

Tamandua. Photo courtesy of Jack Ewing |

If you are planning a vacation, consider visiting someplace that is conserving rainforest or is contributing to the protection of a rainforest. This may require some intensive research on Internet, as few web sites have a list of such destinations. The Rainforest Alliance has what they call the Eco-Index which has information about places they consider to be sustainable. This might be a good place to start. Most good travel guides will give you a pretty good idea about which destinations actually participate in the conservation of the rainforest and which ones only take advantage of the rainforest.

You can contribute directly to organizations that are working actively to conserve the rainforest. The Rainforest Alliance is an example of an international organization that is doing a lot of good. In the area near Hacienda Barú the local organization that is most active is called ASANA. I mention ASANA a lot in Monkeys Are Made of Chocolate.

Mongabay:

Your book is full of great stories. Is there a particularly memorable experience that you would like to highlight?

Monkeys Are Made Of Chocolate: Exotic And Unseen Costa Rica |

Ewing: One of my memorable experiences is told in “More than Green Paint!”, a story that is not in Monkeys Are Made of Chocolate

“Hey, look at this!” I looked up from the advertisement. “There is an Ecological Rent-a-Car” in San Jose. Their cars must be hybrids or run on fuel cells or maybe butane. Isn’t that great?”

My daughter’s tolerant smirk, told me I was way off base. “Oh Daddy, you’re so naive. Ecological’ is a popular word. It attracts customers, so everybody uses it.” That car rental is no different than all the rest.

No to be daunted, I dialed the number and asked the question: “Why are your rental vehicles more ecological than the others.” The line went dead. I called back again, and again the person hung up. Later, a friend called and actually got an answer: “It is only a name. So, what’s the big deal?” said the clerk curtly.

That was 1993 and my daughter was right. “Ecology” had become a magic word in Costa Rica, and it did attract business. The terms “ecology” and “ecological tourism” eventually became so overused, misused and abused that we, at Hacienda Barú National Wildlife Refuge quit using them in our publicity.

Mongabay:

How can someone visit Hacienda Barú?

Ewing:

To visit Hacienda Barú just write an let us know what you have in mind and we will help you. www.haciendabaru.com