Scientists find possible cure for global amphibian-killing disease

Scientists find possible cure for global amphibian-killing disease

mongabay.com

May 23, 2007

Scientists have discovered a possible treatment for the fungal disease that has killed millions of amphibians worldwide.

Presenting Wednesday at the General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in Toronto, Professor Reid N. Harris at James Madison University reported that Pedobacter cryoconitis, a bacteria found naturally on the skin of red-backed salamanders, wards off the deadly chytridiomycosis fungus, an infection cited as a contributing factor to the global decline in amphibians observed over the past three decades.

“The exciting aspect is that we identified at least one bacterium from the skin that in both the dish and on the salamander aids the healing process

one species of bacteria which you could tentatively view as a probiotic,” said Harris, who came to the realization while researching another fungus that attacks amphibian eggs and embryos. He found research by other scientists showed that bacteria on some amphibians produced antifungal compounds.

Tree frog in the Amazon rainforest of Peru. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

|

“So we were starting to work on that and then it suddenly clicked that the emerging fungus killing adults was a chytrid fungus and that the skin bacteria producing antibiotics against the egg fungus could do the same against the chytrid fungus,” explained Harris.

Working with Timothy Y. James of Duke University, postdoctoral assistant Antje Lauer, and his students, Harris showed that the skin bacteria protects salamandars from the killed fungus, though so far, the research has only been conducted in a lab environment.

“There will have to be careful testing,” he said. “Just because on the Petri plate you find a species of bacteria that is anti-chytrid doesn’t mean it’s going to be anti-chytrid on the amphibian. So we’re going to have to do some tests to make sure which ones are actually most affective on the organism. But we did find one.”

Harris hopes that the work could eventually lead to a vaccination campaign to save endangred amphibians from extinction.

|

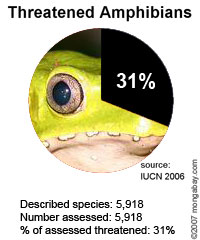

Scientists say amphibians are under grave threat due to climate change, pollution, and the emergence of a deadly and infectious fungal disease, which has been linked to global warming. According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive status assessment of the world’s amphibian species, one-third of the world’s 5,918 known amphibian species are classified as threatened with extinction. Further, more than 170 species have likely gone extinct since 1980. Scientists say the worldwide decline of amphibians is one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group is next.

Due to the crisis, last year 50 of the world’s leading amphibian researchers called for urgent conservation action to save amphibians from extinction. The group, called the Amphibian Survival Alliance, is seeking to raise $400 million to fund captive breeding and conservation programs.