- Rapid agricultural expansion in Kenya’s Trans-Mara District increasingly results in the clearing of the local forest, an important resource for elephant populations that disperse across the Masai Mara-Serengeti ecosystem.

- With limited forest habitat available, elephants increasingly turn to crop raiding, creating fear and anger, and intensifying the conflict between farmers and elephants.

- PhD student Lydia Tiller uses standard technologies in an innovative way to help find solutions to this complex problem.

We’ve all had experiences with that one guest that just won’t leave the party. First you try the subtle approach to get him or her to leave, and then in desperation, the more forceful approach, but s/he still won’t budge. Now imagine that this guest was content to stay on until s/he had eaten every last bit of food you had stored away in your fridge- How would you react?

In the Trans-Mara district, in Kenya, this scenario is more common than you would expect, only that the uninvited guests weigh up to 6 tons and can eat through a whole year’s worth of food supplies in a few hours.

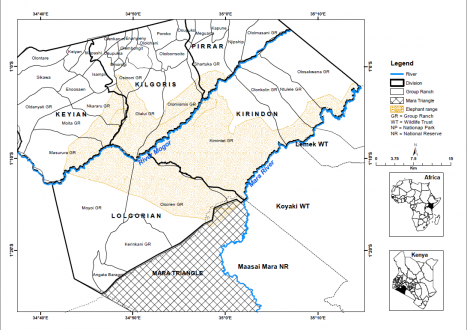

Elephants that raid crop farms can destroy a farmer’s entire season’s worth of harvest in one night. In the Trans-Mara District, an unprotected area adjacent the Masai Mara National Reserve (MMNR) in Kenya, many people grow crops as a livelihood. However, to make way for their crops (and to make a bit of extra money from charcoal production), farmers in the Trans-Mara are clearing the local forest, which is known to be a key resource and habitat for elephants and an important dispersal area for the Mara-Serengeti elephant populations.

The destruction of this habitat is therefore disrupting the natural movement of elephants between the Trans-Mara and the MMNR, and with progressively limited forest habitat available, elephants increasingly turn to crop raiding. As you would imagine, this has a highly negative impact on local farmers and creates fear and anger, intensifying the conflict between farmers and elephants, sometimes resulting in the death of both species.

So how do you keep both people and elephants safe? This is a question that Lydia Tiller, a PhD student at DICE (Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology) in the University of Kent, is working hard to figure out. This young conservationist has been based in the Trans-Mara District since 2014 and is gathering data in order to gain a clearer understanding of how land-use changes (such as forest loss) are driving human-elephant conflict and influencing elephant movement in the region.

Learning about the locals- elephants and people

Although the elephants of the Trans-Mara are an important component of Kenya’s rapidly dwindling populations, surprisingly little is known about their movements and behavior. With the help of modern technology and the local people, Tiller is filling these knowledge gaps by collecting scientific data on this elephant population and their interactions with the local residents of the Trans-Mara District.

With the support of nine local game field scouts, whom Tiller personally trained, she is applying “tried and tested” data collection methods in an innovative way:

“The first step in my study is to identify which elephants use certain pathways, how often and what time of day they travel up and down these pathways, and what characteristics of these pathways might be driving these trends.” explains Tiller. To do this, Tiller and her team are using camera traps along known “elephant pathways”. Using these camera trap images in combination with an elephant photo database, called Elephant Voices, Tiller is able to recognize individual elephants and analyze their movement patterns.

To complement these data, the team conducts ground surveys to detect the presence of elephants along pathways. During the surveys, scouts search for signs of elephants, such as dung (which occasionally contains maize kernels, proving that the poop belonged to an individual who recently feasted in the neighboring crops), broken branches, and footprints.

To find out if crop-raiding events follow seasonal and spatial trends, Tiller’s team also works with local farmers, collecting information on on-going crop-raiding incidences. Interviews with farmers whose crops have been raided reveal when and where crop raiding takes place, how much damage is done, what measures are taken to protect farms, and how effective these measures are. Tiller plans to use this information to assess if particular “crop-raiding hotspot areas” exist, and what actions farmers are currently taking to prevent elephant from damaging their crops.

So what does one do with all this information?

Tiller plans to combine the information she is collecting with data from a study on human-elephant conflict 15 years ago and data on land-use change over the last 30 years (obtained from Google Earth images) to develop a spatial model to highlight human-elephant conflict hotspots and predict possible conservation outcomes under different land-use management scenarios.

“I am hoping that by understanding the current human-elephant conflict situation in the Trans-Mara and the factors that drive it [such as elephant movement patterns and land-use changes], I will be able to develop context-specific recommendations that both maintain habitat and dispersal areas for elephants and mitigate conflict between humans and elephants, essentially protecting the lives of both people and elephants.” Tiller explains.

From Kent to Kenya- the challenges

Although this PhD on human-elephant conflict in the Trans-Mara district will provide much needed information to address the current human-elephant conflict situation, it is easy to see why a study of this scale and magnitude has not been done prior to this – it is a lot of hard work!

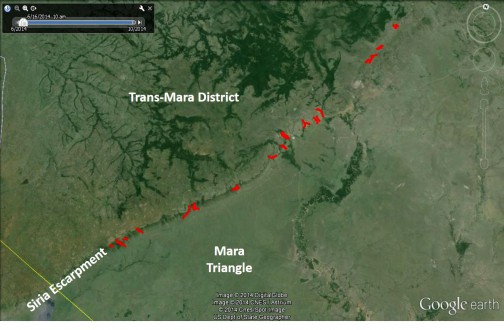

“Ground surveys of the elephant pathways are done on a bi-weekly basis and camera trap data needs to be collected every 2-3weeks.” Tiller describes, as she highlights how data collection is not for the faint of heart. “Each ground survey takes about four days of strenuous hiking to collect the data, because the pathways climb up a steep escarpment, and there are 25 pathways in total.”

In addition to the dedication, not to mention the climbing, required to gather accurate scientific data, Tiller has had to adjust to an entirely new way of living. She lives out in the bush on her own and has had to learn to integrate with people whose culture was very different to her own.

“In the Masai culture, women are expected to stay at home, and many are illiterate, so all my scouts had to be male.” Tiller says, as she describes the challenge of being a young female researcher in the Trans-Mara. “Initially, I had trouble gaining respect from them, and some scouts would simply make up data, but I learned how to deal with the situation and I am now more than happy to leave them in charge of data collection while I am away from the field.”

Although challenging, Tiller suggests that these experiences have allowed her to grow personally, and to cultivate her skills as a researcher- which in her opinion is one of the main reasons for pursuing a PhD.

Findings so far

In addition to her “personal learning experience,” Tiller continues to learn about the elephants and the people of the Trans-Mara. Although she is still conducting research and has not yet done final data analyses, Tiller suggests that some pathways appear to be used more frequently than others, and some are used only by family groups, while others are used only to access crops!

“Perhaps these are promising preliminary findings, as pathways could be monitored according to the risk of use by certain elephant group types.” says Tiller, as she explains how her results could be interpreted for conservation uses.

According to Tiller’s interviews, currently, most farmers are using traditional methods to prevent elephants from destroying their crops, including noise aversion tactics, fire slinging and flashlights; however, her research has shown that these strategies, although useful in scaring elephants away before they get into the crops, are not very effective once elephants are already feeding in the crops.

“In order to minimize human-elephant conflict, I think early detection of approaching elephants is key,” says Tiller. “If we could develop a means of detecting these animals before they get into the crops, farmers have a chance of chasing the elephant away with traditional techniques, before any damage is done, which would prevent further conflict.”

If this is the case, some might suggest that tagging habitual crop-raiding elephants with small short-range RFID tags or large, costly longer-range GPS tags to follow their movements and provide real-time monitoring and an early warning system could be a useful solution.

Current technology does, in fact, allow researchers to set up “virtual fences” that trigger an alert when elephants cross certain points in the landscape. However, the system requires the elephant to be fitted with a GPS tag collar, no easy feat, that is configured with customized real-time monitoring-enabled software. Tiller stresses the importance of effectively detecting elephants without the need for each individual to wear a collar. An alternative answer could lie underground, in the form of fiber optic cables and other seismic sensors that detect presence of moving animals and, increasingly, can distinguish elephants from other species.

We will have to wait until the end of Tiller’s PhD to learn more about how elephants and people are using the Trans-Mara corridors and the technological and land-use management recommendations she proposes for reducing human-elephant conflict in the region. Tiller has little doubt that something needs to be done soon, before it is too late to save this elephant population that plays such a pivotal role in broader ecosystem functioning.