Palm oil fresh fruit bunches in Indonesia. Photo: Rhett A. Butler

Last summer, an Indonesian NGO published research showing that an oil palm developer controlled by one of the country’s richest businessmen was clearing dense rainforest in New Guinea despite promises by its biggest customers to purge their supply chains of deforestation.

Nearly a year later, the company’s bulldozers are still at work, and multinational palm oil traders Asian Agri and Musim Mas, which have each signed high-profile no-deforestation commitments, are still sourcing it, according to the latest report by the NGO, Greenomics-Indonesia.

Wilmar, another palm oil titan, put its business with the company, Austindo Nusantara Jaya (ANJ) Agri, on hold in April, though it waited nine months from the release of Greenomics’ first report to freeze the relationship.

The latest report, released last week, throws the spotlight on Golden Agri-Resources (GAR) as ANJ Agri’s biggest buyer in the first quarter of this year, during which time GAR spent $13.5 million on crude palm oil from ANJ and accounted for 43 percent of its sales.

This evening, a GAR spokesman capped an email exchange with Mongabay with the news that it would join Wilmar in suspending its dealings with the company.

“Following serious allegations against our supplier ANJ Agri regarding clearance of [high-carbon stock, or HCS, forest] in [Indonesia’s West Papua province], we have immediately engaged with them to investigate the issues,” the spokesman said.

“Our view is that ANJ should immediately suspend all clearance pending further [high-conservation value, or HCV] and HCS studies.

“In the meantime, we are with immediate effect suspending any new purchases from ANJ.

“We are reviewing existing procurement arrangements in light of recent developments.”

Asian Agri and Musim Mas have given no indication that they will follow suit, though their policies, like Wilmar and GAR’s, prohibit the destruction of HCS forest, defined as containing more than 35 tons of carbon per hectare, a description that generally applies to any forest more robust than shrubland. [Update: After the publication of this article, Musim Mas informed Mongabay that if ANJ failed to produce an HCS assessment by the end of May, it would put its dealings with the supplier on hold.]

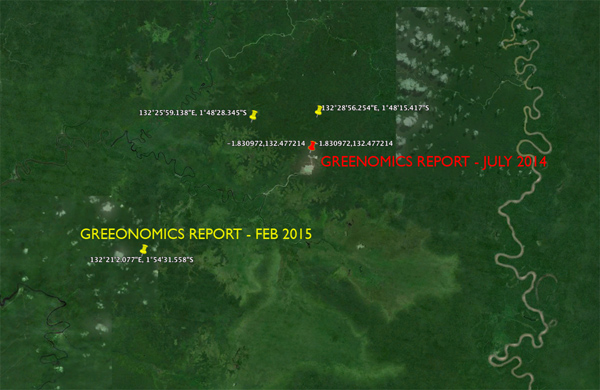

Greenomics map showing recent clearing by Austindo Nusantara Jaya Agri in West Papua, Indonesia

According to satellite analysis and field checks by Greenomics, the two ANJ concessions in question consist of intact forest landscapes that might contain old-growth primary as well as regenerating secondary forest.

Wilmar stopped buying from ANJ in April when the latter missed its own deadline for carrying out an HCS assessment in the concessions, according to a Wilmar spokesman.

Wilmar had reached out to the company in February after Greenomics put out a second report. At the time, Wilmar said it was unaware of the clearing – it noted that no one had filed a grievance via its online complaints system – but promised to investigate the matter.

Besides announcing their own sustainability commitments, Wilmar, GAR, Asian Agri and Musim Mas, along with Cargill and the Indoneisan Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin), have signed the Indonesia Palm Oil Pledge (IPOP), which obliges them to lobby the Indonesian government to make deforestation illegal.

Google Earth images showing points of clearing by Austindo Nusantara Jaya Agri in Indonesian New Guinea. Click images to enlarge.

According to Greenomics’ latest report, “IPOP does not seem to be playing an important role in identifying the various problems and challenges faced by the IPOP signatories in fulfilling their pledges at the implementation level.”

Vanda Mutia, Greenomics’ executive director, criticized Wilmar for waiting as long as it did to act on ANJ’s forest clearing and buying from the company all the while. (GAR had yet to announce the buying freeze when she made the comments.) Wilmar’s delayed response, she told Mongabay, “[shows] that its policy implementation is under no serious monitoring.”

Companies with sustainability commitments, as well the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), an eco-certification initiative that requires companies who choose to join to abide by certain social and environmental criteria, have been criticized for simply reacting to violations when NGOs or journalists point them out rather than preventing them from happening in the first place.

For example, ANJ is an RSPO member, and under the RSPO’s New Plantings Procedure (NPP), any plantings begun after January 1, 2010, must be preceded by a high-conservation value (HCV) assessment and a social and environmental impact assessment (SEIA) by RSPO-approved assessors. However, in July 2014 when Greenomics released its first report on ANJ’s forest clearing, it came to light that the company had ignored the RSPO’s requirements and that the RSPO had done nothing about it.

In response, ANJ declared a moratorium on forest clearing in the concessions while it completed the NPP process, after which it resumed clearing.

Unlike the IPOP, the RSPO does not prohibit the clearing of all forests, just forests with high conservation values.

The ANJ conglomerate, of which ANJ Agri is a subsidiary, is listed on the Indonesian Stock Exchange. ANJ’s owner and CEO, George Tahija, sits on the board of The Nature Conservancy-Indonesia, an arm of international conservation giant TNC. Greenomics has called on TNC to pressure the company through its relationship with Tahija to stop destroying forest.

In an email to Mongabay, ANJ Agri Sustainability Director Sonny Sukada did not deny the company was clearing forest but emphasized HCS “is a new concept which needs further looking into especially with respect to agricultural development in West Papua” and that ANJ was taking steps to undertake a full HCS and HCV review.

“We would like to take this opportunity to clarify that development in West Papua is complex and HCS clearance as accused by Greenomics-Indonesia is but one element,” he said. “We are faced with the challenge of promoting and establishing sustainable agriculture in this economically challenged region.”

He added, “The tropics are full of examples of development by ‘irresponsible parties’ and in most cases nothing really can be done to stop these. ANJ is a very responsible commercial agent of change.”

A further concern about ANJ’s Papua operations is that the ANJ Agri subsidiaries in question, Permata Putera Mandiri (PPM) and Putera Manunggal Perkasa (PMP), apparently obtained the various permits the need to operate in a legally irregular sequence.

According to the companies’ NPP submissions, accessible on the RSPO website, they each received a Social and Environmental Impact Assessments (AMDAL) from the Indonesian government after getting a Plantation Business Permit (IUP), which gives companies the right to operate. In fact, the AMDAL must come before the IUP.

Such irregularities are widespread in the Indonesian palm oil industry, said Jago Wadley, a senior forest campaigner with London-based NGO the Environmental Investigation Agency, whose 2014 report titled “Permitting Crime: How palm oil expansion drives illegal logging in Indonesia” provides evidence that plantation developers regularly flout the AMDAL requirement, which is meant to give local communities and civil society a chance to weigh in on projects affecting them.

Sukada pointed out that ANJ did not purchase PPM and PMP until 2013, when all AMDALs and IUPs had been acquired.

“The point about legal sequencing is a query on retrospective actions not undertaken by ANJ as the development sites were purchased in 2013 when all legal obligations were settled by the previous owners,” he said. “We are not in a position to query this on your behalf and it is rather pointless as the legalities irrespective of sequencing have all been dealt with by the previous owners.

“ANJ will in the coming months make public its plans and intentions to prevent further accusations from surfacing. Your future queries are welcome and at that point we hope to provide a very positive picture of our development. A balanced view.”