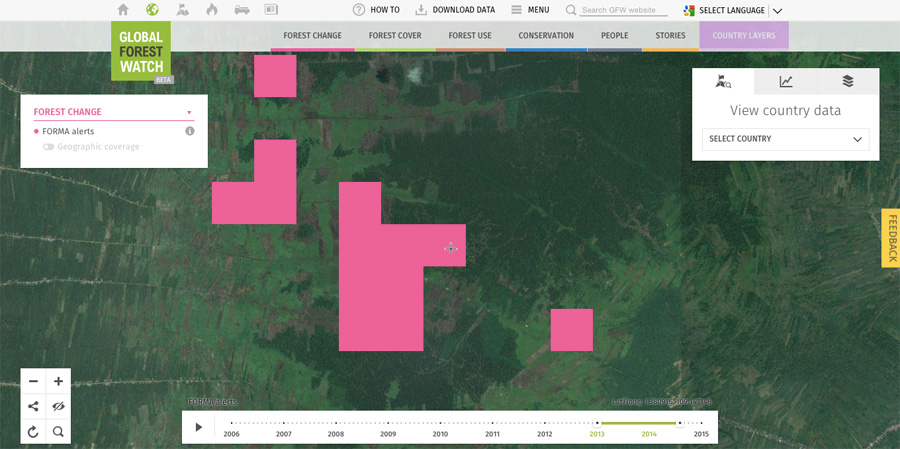

Google Earth image showing GPS points where forest loss occurred within the past year in a West Kalimantan concession held by PT Bumi Mekar Hijau (BMH).

The apparent loss of some 4,000 hectares of forested peatland in Indonesian Borneo is raising questions on who bears responsibility for forest clearing in un-utilized concessions.

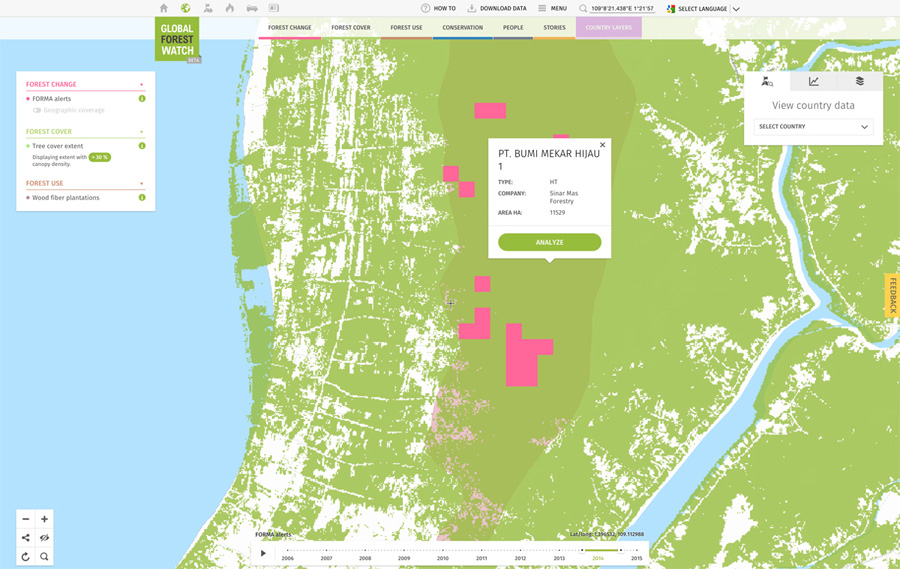

On Monday, Greenomics-Indonesia issued a report revealing the loss of significant tracts of peat forest in a West Kalimantan concession held by PT Bumi Mekar Hijau (BMH), a plantation company whose operation in South Sumatra supplies Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) with woodpulp for its mills.

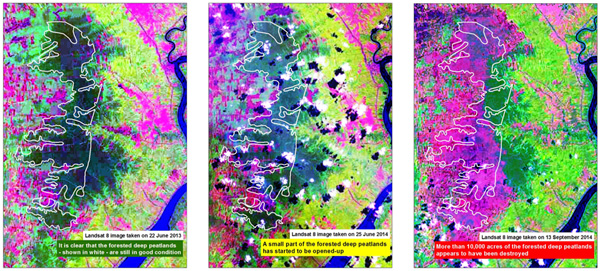

The findings are based on Greenomics’ analysis of Landsat images and legal documents from the Ministry of Forestry. The images show loss of vegetation cover between June and September 2014, while the legal documents link BMH to Sinar Mas, the parent of APP. The forest loss data is corroborated by Global Forest Watch, whose FORMA near-time forest alert system shows loss during the time period.

Analysis of NASA Landsat images by Greenomics.

Given the data, at first glance the situation looks like another text book case of a company destroying forests to establish a plantation. Accordingly, Greenomics called on APP to suspend its contract with BMH, arguing that the activity represented a potential breach of APP’s zero deforestation commitment even though APP only sources fiber from BMH’s South Sumatra concession.

However the situation appears to be more complex on the ground. Critically, BMH apparently isn’t currently operating in the concession area, according to APP, which dispatched an investigative team over the weekend to conduct field checks on GPS points cited in the Greenomics report.

“Based on the information provided by the community, no companies are operating in BMH West Kalimantan, including: no BMH West Kalimantan’s camps, supporting infrastructure, land clearing or planting,” Aida Greenbury, APP’s managing director of sustainability, told Mongabay. “The area has been largely occupied with villages of Sambas Malay community.”

Greenbury said that while BMH secured a license from the Ministry of Forestry to convert the area for timber plantations, the company was refused entry by the local community when it tried to conduct field surveys in 2008 and 2009. Since then, there has effectively been a stand-off in the area.

Global Forest Watch image showing recent FORMA alerts within BHM’s concession area. According to Global Forest Watch, the concession lost 3,448 hectares — 30 percent of its land area — between January 2008 and December 2013. Click images to enlarge.

Global Forest Watch image showing recent FORMA alerts within BHM’s concession area. According to Global Forest Watch, the concession lost 3,448 hectares — 30 percent of its land area — between January 2008 and December 2013. Click images to enlarge.

In the meantime however, satellite images show that forest is disappearing. APP’s investigative unit was able to visit two of the GPS points (109°8’14.915″E 1°24’36.811″N and 109°8’59.117″E 1°23’38.237″N), finding damaged forests.

“They found the area as an open, ex burnt thin natural forest area, after the wildfire in October 2014,” said Greenbury. “No community, company, or any previous plantation activity in those coordinates.”

The other two points were unreachable due to difficult terrain, but the team did find extensive encroachment for community rubber and coconut plantations. There are also community oil palm plantations in the area.

Photo from one of the GPS points. Courtesy of APP.

Those findings suggest the ongoing clearance of peat forests in the concession area may be difficult to address since it falls outside APP’s zero deforestation commitment. Therefore the fate of the remaining forests may be in the hands of the community and the local government.

The situation isn’t unique to West Kalimantan — these issues crop up regularly across Indonesia, which continues to be plagued by poor land titling systems, weak law enforcement and governance, and social conflict. Problems often arise in places where large blocks have been licensed for industrial conversion, including some areas that have been traditionally used by communities or have been colonized by transmigrants under Indonesia’s population relocation program. These enduring issues help explain why Indonesia’s progress in reducing deforestation has been so slow.

For example, palm oil companies that try to protect high conservation value and high carbon stock forests within their concessions under their sustainability commitments risk having those areas clawed back by the government and turned over to entities that have no qualms about clearing them. And many companies have complained about “encroachment” into their legally-mandated forest reserves. On the other side, villages often protest the seizure of community forests for logging, mining, and conversion to plantations. Those protests are at times with violent suppression by security forces that in practice rarely face prosecution for crimes.

Peat forest in West Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett Butler

The extent to which these issues apply specifically to the BMH concession are unclear — on-the-ground details remain sparse due to the remoteness of the area and the breaking news nature of the information. Accordingly, Greenomics is calling for “an independent multi-stakeholder investigation” to understand “the direct and indirect causes of the loss of the peatlands” in the area.

For its part, APP said work on the ground by NGOs could help determine why the forest is being cleared and what can be done to save it.

“What is the legal status of these community plantations and do they have traceability systems?” asked Greenbury. “These are some of questions that need to be answered.”