Puma that was hit by a vehicle in the state of Sao Paulo. Photo by ZOO/BAURU.

Brazilian biologist Alex Bager has been leading a crusade to raise awareness of a major but neglected threat to biodiversity in his country.

Every year over 475 million animals die in Brazil as victims of roadkill, according to an estimate by Centro Brasileiro de Ecologia de Estradas (the Brazilian Centre for the Study of Road Ecology) or CBEE, an initiative funded and coordinated by Bager. This means 15 animals are run down every second on Brazilian roads and highways.

“The numbers are really scary and we need people to know about them,” Badger said.

To register cases of roadkill throughout the country, Bager came up with the idea of an app, now used by thousands of citizen scientists. And a national day of action in November saw hundreds of volunteers participate in events to highlight the impact of roadkill on biodiversity.

Mobile app promotional images run on Facebook. Photo by Alex Bager

Estimates

Bager, a biology professor at the Federal University of Lavras, in the state of Minas Gerais, presented his estimate at the Brazilian Congress on Road Ecology earlier this year and aims to publish a detailed study on the figures in 2015.

How did he reach the estimate of 475 million?

“We based our estimate on 14 scientific studies on this problem in different parts of the country. This allowed us to calculate a roadkill rate that we adjusted according to the type of road, area, local biodiversity etc.,” Bager explained. “Finally we extrapolated the data to the massive Brazilian road network of 1.7 million kilometers and compiled the estimate for the whole of the country.”

Brazil’s great biodiversity combined with an expanding road network are a perilous combination, according to Bager, who said that “our estimate is quite conservative, we fear the real numbers are even higher.”

Crab eating fox. Photo by Alex Bager

Cougars

About 90 percent of the animals killed are of small size, like amphibians, birds and small rodents and turtles. Medium sized animals such as opossums and hares or bigger birds such as hawks and vultures represent 9 percent of the victims.

“Big animals make up one percent of the total, but we are talking about 5 million animals, including capybaras, crab eating foxes, and tapirs, as well as big cats such as cougars and jaguars,” said Bager.

Many endangered species are being seriously affected.

“One of the most worrying situations is that of cougars (Puma concolor). Many cases have been reported in the state of Sao Paulo, which has an extensive road network, but we know of cougars killed in the Northeast, in Mato Grosso, in Rio Grande do Sul, in Pantanal,” Badger noted. “The cougar is a very plastic species, it manages to survive relatively well in agricultural areas, such as sugar cane fields, so it ends up approaching many roads and highways”.

Badger said the cougar is facing a number of pressures that are making survival increasingly difficult

“[The cougar] needs a lot of space to move to find food, places to sleep, and each day is more surrounded, fenced by highways, cities, agricultural fields, people. This species really faces a daily dilemma, between moving to satisfy its needs and the risk of being struck down by a vehicle.”

Cougar after a collision in the state of Sao Paulo. Photo by ZOO/BAURU

Tapirs

Other species widely affected are the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), as well as the Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestris), and crab-eating foxes (Cerdocyon thous).

Biologist Patricia Medici, who coordinates the National Initiative for the Conservation of Brazilian Tapirs, says roadkill has a serious impact on this species.

“We monitored during one year three segments of roads connecting Campo Grande to other cities in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul and registered 36 tapirs struck down. This is a species that is slow to reproduce se we are talking of a significant impact”.

Capybara crossing a road. Photo by Alex Bager

Citizen scientists

To gather more data about the impact of roadkill, Bager worked with developers to create an app for smartphones.

“This is one of the best examples of citizen science in Brazil I am aware of,” he says. The app is called Urubu mobile, a tongue-in-cheek reference to the word in Portuguese for black vulture, an animal that looks for carcasses.

“When somebody sends a photo of a roadkill the exact site is registered with GPS. We have over 6.000 registered users in the whole of the country,” Badger said, adding. “Anybody can join.”

The app is part of a wider Urubu System. Each photo is analyzed by five researchers from a team of 500, and only then is integrated into a map that visualizes key problem areas throughout the country.

Overpasses and underpasses

Bager hopes the information will be the basis for new legislation.

“We are already working with government bodies and three members of the federal Parliament in the capital, Brasilia, to create a new bill,” he said. “There are currently no federal laws regulating what studies need to be done and what measures implemented to reduce the impact of roadkill. We also want to set up a special biodiversity fund to tackle the problem.”

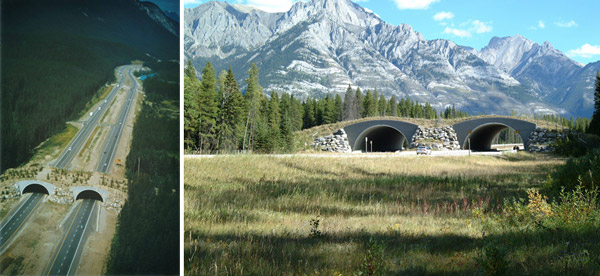

Warning sign and wildlife overpasses in Banff National Park. Photos courtesy of Susan Hagood, Humane Society of the United States (HSUS)

Ultimately, Bager envisages very practical solutions such as the overpasses and underpasses that protect animals from collisions at Banff National Park, which is crossed by the Trans-Canada Highway.

Medici would also like to see the introduction of radars for speed control, since in many cases roadkill happens because drivers exceed the speed limits.

These changes would be the culmination of more than a decade of work for Bager, whose interest on roadkill was sparked while he was researching turtles in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in the south of the country.

“I had to travel 100 kilometers from the university to the Taim Ecological Station to study the turtles, and I used to find many animals killed on the roads,” he said. “With my students we became interested and started looking into the impact of road kill in 2002.”

By 2011, now at the University of Lavras, Bager founded the Brazilian Centre for the Study of Road Ecology.

The work of the biologist and his colleagues is a race against time.

“It is crucial that we find a solution because the problem is growing as Brazil develops and expands its road network,” said Badger. “If today we see over 400 million animals killed every year, this means if we don’t act or we could end up losing entire species.”