A poster-child for rare species: the Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) captured on camera trap in its last stand: Ujung Kulon National Park Java, Indonesia. Photo by: © Mike Griffiths / WWF-Canon.

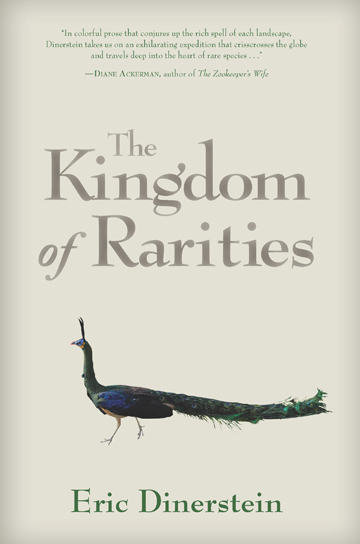

In his new book, The Kingdom of Rarities, Eric Dinerstein chases after rare animals around the world, from the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) in Brazil to the golden langur (Trachypithecus geei) in Bhutan to Kirtland’s warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in the forests of Michigan. Throughout his journeys, he tackles the concept of rarity in nature head-on. Contrary to popular belief, rarity is actually the norm in the wildlife world.

“Most people, and even many scientists remain unaware that the vast majority of species on Earth are considered to be rare,” Dinerstein told mongabay.com in a recent interview. One of the difficulties of modern conservation is determining which species are naturally rare, and thus have special adaptations to survive in low numbers, and which have been made rare by the increasingly-massive human footprint.

“Some species have always been rare, such as species that live in unusual habitats on the tops of single tropical mountains. Then there are creatures like the five living rhinoceros species that were widespread and abundant until humans started to hunt or poach them and convert their habitats to agricultural crops. As conservationists it’s vital to distinguish between [these],” says Dinerstein.

|

But being rare doesn’t mean a species has no ecological importance. In fact, some of the animals with the smallest density have the biggest impacts.

“We know from field studies that when you remove tigers or jaguars from an area, the ecosystem can go haywire, with populations of leaf-eating creatures exploding as there is no longer any predator to keep them in check,” explains Dinerstein. “Think of how the absence of a rare predator—mountain lions or wolves—enables the severe overpopulation of white-tailed deer in the eastern U.S. Even at very low densities, if we had mountain lions around, white-tailed deer would not be strolling through suburban neighborhoods as if they were on a garden tour.”

Many of the world’s rare species have become “quest species” for biologists and wildlife enthusiasts, according to Dinerstein, who defines quest species as an animal that “‘haunts your existence.'”

In the midst of what many scientists say could become a global mass extinction, Dinerstein sees hope in the recovery of once-rare species such as the white rhino as well as in countries like Bhutan where nature-protection has become not only a part of the cultural and religious fabric, but also government policies.

“I think we are still in the early stages of our cultural evolution as a species, and one marker of how we have progressed is our willingness to coexist and even celebrate natural rarities,” Dinerstein says. “I believe we will get there, even if in fits and starts. I see the next two decades as a holding action, to stave off extinctions until this more benign view becomes more widespread.”

INTERVIEW WITH ERIC DINERSTEIN

Snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is exceedingly rare, and almost impossible to see, although it survives in a massive range. Photo by: © Bruce W. Bunting / WWF-US.

Mongabay: What’s your background?

Eric Dinerstein: A late bloomer as a biologist and naturalist, I thought I was going to be a filmmaker and went to film school at Northwestern University, only discovering that I wanted to be a biologist when I was a junior in college. I had a lot of catching up to do, and I attended three different colleges before I settled down to earn a degree. I still wasn’t sure of my direction until, on a whim, I joined the Peace Corps and was sent to Nepal to census tigers in a newly created tiger reserve. I never looked back. After a five-year post-doc with the Conservation and Research Center of the National Zoo—spent all in Nepal studying rhinos and tigers—I joined World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and have been there for the past 24 years. So I am a living example for parents who worry about their kids having no clue about their future career path and seeming lost in college, to tell them to be patient, that eventually it all works out.

RARITY IN NATURE

Mongabay: What intrigues you about rarity in nature?

Eric Dinerstein: I suppose the shocking observation that rarity is not rare. Most people, and even many scientists remain unaware that the vast majority of species on Earth are considered to be rare.

Eric Dinerstein points to giant panda sign in a panda reserve, Wanglang, in Szechuan Province China. Photo by: © Colby Loucks / WWF-US. |

Let’s unpack what it means to be rare. The first part of the definition is a species with a very narrow range, like the Javan rhinoceros, found only on the extreme western tip of the island of Java, near the Krakatoa volcano. Rare species can also be widespread but occur at very low densities, like jaguars or tigers or great white sharks. Finally, some species can show both qualities—a narrow range and a low population density like the Kirtland’s warbler, the rarest breeding songbird in North America, whose nesting habitat is a small patch of young pine forest near Grayling, Michigan.

Mongabay: How do we differentiate between species that are naturally rare and those that are made rare by humans?

Eric Dinerstein: Great question. Some species have always been rare, such as species that live in unusual habitats on the tops of single tropical mountains. Then there are creatures like the five living rhinoceros species that were widespread and abundant until humans started to hunt or poach them and convert their habitats to agricultural crops. As conservationists it’s vital to distinguish between species that have always been rare and evolved mechanisms or behaviors (what scientists call adaptations) to deal with their low numbers or limited range. These traits could be much different than those exhibited by species that were once ubiquitous but made rare by human activities in the recent past. They may be much less equipped to deal with their new status and survive and breed. So the strategies we use to conserve each group might be different. Knowing that can make us more efficient in how we design conservation strategies.

Mongabay: How do rare species still have large impacts on ecosystems?

Eric Dinerstein: Some great examples are elephants—African or Asian, take your pick—and top predators. We think of the largest herbivores—we call them megaherbivores—as landscape architects or landscape engineers, that through their grazing, browsing, trampling, wallowing, and yes, even manuring, change the structure of the landscape, often in ways that benefit many other species that live in the same area. We know from field studies that when you remove tigers or jaguars from an area, the ecosystem can go haywire, with populations of leaf-eating creatures exploding as there is no longer any predator to keep them in check. Think of how the absence of a rare predator—mountain lions or wolves—enables the severe overpopulation of white-tailed deer in the eastern U.S. Even at very low densities, if we had mountain lions around, white-tailed deer would not be strolling through suburban neighborhoods as if they were on a garden tour.

Mongabay: What role do greater one-horned rhinos play in their ecosystem?

Akohekohe or the Crested honeycreeper (Palmeria dolei) Drawing by: © Paul Barruel / WWF. |

Eric Dinerstein: Gardeners extraordinaire. Embedded in the dung of these behemoths are the seeds of certain plants that rely heavily on these rhinos to disperse their seeds. One tree, I dubbed the rhino apple, produces a fruit the rhinos devour and then pass the seeds in their dung. And what dung they produce. I once weighed a fecal gift that could find a place in the Guinness book of records—54 pounds of dung in a single defecation! When these defecations occur on latrines, where rhinos come back again and again to do their business, clumps of forest can spring up in the grasslands. What biologists call the “seed rain” into these sites can be so heavy that the rhinos have the potential to rapidly turn their grassland homes into rhino apple forests. Another important influence is how their browsing also diminishes the growth of tree species they like to eat. One could say that in a forest where elephants and rhinos still occur, even at what we call low density, the trees that reach the canopy are the ones that as seedlings and saplings are unpalatable to rhinos.

Mongabay: Does a species confer any advantages by being rare?

Eric Dinerstein: A lot of great scientific minds have put considerable thought into this intriguing question, and I canvassed a number of them to seek an answer. The consensus is an emphatic “No.” In the book I explain why.

Mongabay: How many individuals do you need for a species to keep up its ecological role, i.e. at what level should we start considering species “ecologically extinct?”

Eric Dinerstein: Great point for debate among ecologists. Certainly, top carnivores like tigers and lions and jaguars can still play their roles living at densities of 3-4 individuals/100 km2. At the other extreme, some ecologists argue that for caterpillar-consuming birds, like our migratory wood warblers that vacuum up insect pests in the eastern forests of the U.S., to play their ecological role, they need to be in really abundant flocks. The answer will vary for different sized species with different ways of feeding. Would that we should be so successful in conservation that we can someday retire this question from the conversation!

CONSERVATION OF RARITY

Two African elephants (Loxodonta africana). African elephants are colossal ecosystem engineers. Photo by: © Howard Buffett / WWF-US.

Mongabay: What are some conservation stories that we can learn good lessons from?

Eric Dinerstein: That of the southern white rhino is the best one. Here we have one of the world’s largest land mammals, a relatively slow breeder, and a species widely persecuted for its horn. Around the year 1900 its numbers were down to fewer than 100 in a single reserve. Today, there are more than 20,000 free-ranging southern white rhinos among 483 populations. So if anyone thinks that it is a waste of time to save endangered rarities, talk to those who saved the southern white rhino. If we can save this giant, slow-breeding, highly persecuted species, we can restore practically any rarity if we have the will.

I could also point to the heroic efforts of biologists in Hawaii bringing back rare species. The Hawaiian Islands are our own Galapagos, jewels for studying the handiwork of evolution. We should be tripling the budgets of federal conservation agencies charged with saving rare birds and mammals found there. I cover some of these efforts in the book. A great place to learn about the rarest of the rare, and some real success stories for conserving them that is happening in real-time, is to go to the website of a group I had a small part in founding, the Alliance for Zero Extinction (www.zeroextinction.org). AZE focuses on around 600 sites globally, including around 900 species whose sole place to live is a single site and who are considered Critically Endangered or Endangered by the IUCN.

Mongabay: In your book you write about the positive role religion can play in conservation, will you expand on this for us?

Kirtland’s warbler. Around 5,000 of this songbird survive. Drawing: WWF/Paul Barruel. |

Eric Dinerstein: Many conservationists and religious leaders have joined forces to recognize the intrinsic beauty and value of nature and its rarities. It’s a match that should have happened long ago. In the chapter on Bhutan, I illustrate one solution to our predicament, where a country has sought to merge the Tibetan Buddhist dharma with the principals of conservation biology and then write it all into their constitution. Where else in the world are networks of protected areas and the corridors that connect them part of the legal fabric of a nation? I think we are still in the early stages of our cultural evolution as a species, and one marker of how we have progressed is our willingness to coexist and even celebrate natural rarities. I believe we will get there, even if in fits and starts. I see the next two decades as a holding action, to stave off extinctions until this more benign view becomes more widespread.

Mongabay: Given that many scientists now believe we are on a cusp of mass extinction, where do you find hope in conservation?

Eric Dinerstein: My hope draws from the resiliency we see in nature and in the species we are trying to save. Give species and their habitats half a chance and they come roaring back. In poor countries, it’s often a matter of getting the incentives right to tilt the needle back toward conservation. We have so many success stories where political will, funding, and on-the-ground efforts have all come together. Peregrine falcons, bald eagles, southern white rhinos, the list goes on. We tend to dwell on the failures, but they are more failures of will than anything else.

Mongabay: If you could save one species from extinction what would it be?

Eric Dinerstein: Probably the Javan rhinoceros. It survived the eruption of Mt. Krakatoa in 1883 and the subsequent tsunami. It is an ancient mammal that was so common in the early 19th century that it was shot as a pest by Dutch tea planters during the colonial period. Today there are less than 50 left in one site—a second population, in Vietnam, having been wiped out in the last few years.

Mongabay: Who would you most like to read your book?

Jaguar in Brazil. Photo by: © Michel Gunther / WWF-Canon. |

Eric Dinerstein: That’s easy. The political leaders of the nations where rarities really concentrate, mainly in the tropical countries, although every country has its rarities. A few years ago, I was involved with other colleagues from WWF and the World Bank and Smithsonian to create the Global Tiger Summit that was hosted by Vladimir Putin in St. Petersburg, Russia in 2010. It was so successful that in 2013 we are helping to stage a similar event for snow leopards hosted by the President of Kyrgyzstan. There is no substitute for having political support at the highest levels of government. I am impressed with how much our Global Tiger Initiative—started by the President of the World Bank at the time, Robert Zoellick—has advanced tiger conservation in the two years since the tiger summit. Imagine if we could do the same for other charismatic species. That’s almost a subject for another session with your Mongabay readers.

Mongabay: What’s next for you?

Eric Dinerstein: I’m deeply involved with fellow WWF scientists in a number of ground-breaking conservation projects, a few of which are briefly mentioned in the book as possible solutions to making rare species—whose ranges or abundance had been so heavily reduced by human activities—to become common again. One idea, called the Wildlife Premium Mechanism, supported by the World Bank, is an idea that may be familiar to devoted Mongabay readers. Simply put, we are trying to add value to restoring endangered, charismatic, and wide-ranging large mammals. One way is to offer buyers of carbon credits in tropical forests the chance to help restore tigers, elephants, gorillas, jaguars, orangutans, lemurs and the like by paying a slightly higher price for the credits if local communities agree to performance-based payments to do so. So this could be a win-win-win: local communities who have management rights over forests earn more income from protecting their forests if they agree to targets to restoring the endangered mammals that live in them. Another project focuses on shifting the expansion of agricultural commodity crops in the tropics from cutting down intact rainforest to making good use instead of degraded lands. Another project, financed by Google, is to use clever new technologies to protect many of the high-value species portrayed in this book—rhinos, tigers, elephants—from highly organized poachers.

In the book, I also introduce the concept of a “quest species,” defined by one biologist portrayed as “a species that haunts your existence. One that you must see before you die.” In this book, I feature many quest species. I suppose my next one is the snow leopard. I have never seen one in the wild, only tracks.

And in my “spare time,” I’m trying to become fluent in German and writing a new book.

Southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum). Photo by: © Martin Harvey / WWF-Canon.

Related articles

(02/12/2013) Nearly half of India’s wildlife budget goes to one species: the tiger, reports a recent article in Live Mint. India has devoted around $63 million to wildlife conservation for 2013-2013, of which Project Tiger receives $31 million. The Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) is currently listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List; however India is also home to 132 species currently considered Critically Endangered, the highest rating before extinction.

Pity the pangolin: little-known mammal most common victim of the wildlife trade

(02/11/2013) Last year tens-of-thousands of elephants and hundreds of rhinos were butchered to feed the growing appetite of the illegal wildlife trade. This black market, largely centered in East Asia, also devoured tigers, sharks, leopards, turtles, snakes, and hundreds of other animals. Estimated at $19 billion annually, the booming trade has periodically captured global media attention, even receiving a high-profile speech by U.S. Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, last year. But the biggest mammal victim of the wildlife trade is not elephants, rhinos, or tigers, but an animal that receives little notice and even less press: the pangolin. If that name doesn’t ring a bell, you’re not alone.

China’s forest privatization move threatens pandas

(02/08/2013) China’s decision to open up collective forest for sale by individuals to outside interests will put 345,700 hectares or 15 percent of the giant panda’s remaining habitat at risk, warns a letter published in the journal Science.

Catching Borneo’s mysterious wild cats on film

(02/07/2013) In my childhood’s biology books from the 50’s, the Australian marsupial tiger Thylacine is classified rare but alive. Today we know that the last thylacine died in a Tasmanian zoo 7th September, 1936, after a century of intensive hunting encouraged by bounties. The local government had finally introduced official protection 59 days before the last specimen died. Despite the optimism in my old books, no more thylacines were ever found. No film of it in the wild exists.

Over 11,000 elephants killed by poachers in a single park [warning: graphic photo]

(02/06/2013) Surveys in Gabon’s Minkebe National Park have revealed rare and hard data on the scale of the illegal ivory trade over the last eight years: 11,100 forest elephants have been slaughtered for their tusks in this remote protected area since 2004. In all, poachers have cut down the park’s elephant population by two-thirds, decimating what was once believed to be the largest forest elephant population in the world.

U.S. proposes to list wolverine under Endangered Species Act

(02/05/2013) Arguably one of the toughest animals on Earth, the wolverine (Gulo gulo) may soon find itself protected under the U.S.’s Endangered Species Act (ESA) as climate change melts away its preferred habitat. Last week, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) announced it was proposing to place the world’s largest terrestrial mustelid on the list. Only 250-300 wolverines are believed to survive in the contiguous U.S.

Sri Lanka to give poached ivory to Buddhist temple, flouting international agreements

(02/05/2013) The Sri Lankan government is planning to give 359 elephant tusks to a Buddhist temple, a move that critics say is flouting the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The illegal tusks were seized in Sri Lanka last May en route to Dubai from Kenya; they are believed to stem from hundreds of butchered elephants, including juveniles, inside Africa, possibly Uganda. The decision comes after a high-profile National Geographic article, Ivory Worship, outlined how demand for ivory religious handicrafts, particularly by Catholics and Buddhists, is worsening the current poaching crisis. In 2011, it was estimated that 25,000 elephants were illegally slaughtered for their tusks.

Geneticists discover distinct lion group in squalid conditions

(02/04/2013) They languished behind bars in squalid conditions, their very survival in jeopardy. Outside, an international team of advocates strove to bring worldwide attention to their plight. With modern genetics, the experts sought to prove what they had long believed: that these individuals were special. Like other cases of individuals waiting for rescue from a life of deprivation behind bars, the fate of those held captive might be dramatically altered with the application of genetic science to answer questions of debated identity. Now recent DNA analysis has made it official: this group is special and because of their scientifically confirmed distinctiveness they will soon enjoy greater freedom.