First camera trap photo of a jaguar taken by Panthera in a deforested area of Costa Rica’s Barbilla-Destierro SubCorridor. Photo by: Panthera.

Jaguar conservation has received a huge boost in the past few months both in Latin America and in the U.S. An historic agreement singed between the world’s leading wild cat conservation organization Panthera and the government of Costa Rica in addition to a new U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) proposal bring renewed hope to the efforts to revive the iconic jaguar in its current habitat and return the cats to the American Southwest.

On July 5th, Costa Rica’s Minister of Environment, Energy and Telecommunications (MINAET), Dr. René Castro, presided over the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the government and Panthera head, Dr. Alan Rabinowitz, who is also a noted jaguar expert.

The MOU establishes an official jaguar conservation strategy in Costa Rica and recognizes a jaguar wildlife corridor as a conservation priority. According to a Panthera press release, both groups in the partnership “commit to carrying out rigorous scientific and conservation initiatives that will help in securing protected wild lands linking jaguar populations in Costa Rica and beyond, as well as ensure that the development of land around these protected areas is done in a way to benefit both wildlife and local communities.”

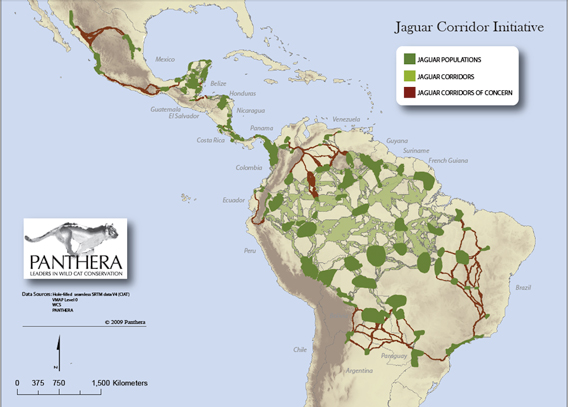

Contiguous protected areas in Costa Rica are a critical part of Panthera’s Jaguar Corridor Initiative , which involves governments, farmers, private landowners, ranchers, and other environmental organizations in the effort to ensure that jaguars have a zone of safe passage throughout their range, made up of 18 Latin American countries, from Northern Argentina to Mexico. Panthera is undertaking initiatives to protect the jaguars in 13 of the 18 countries.

“The signing of this historic agreement marks a turning point for the future for the jaguar not only in Costa Rica, but for jaguars throughout Central and South America,” Rabinowitz said. “This represents the fourth MOU that Panthera has signed with a Latin American government and once executed, will allow Panthera to better implement a ‘connect and protect’ strategy that links and allows safe passage for jaguar populations throughout the species’ range, from northern Mexico, through the heart of Costa Rica, to Argentina.”

Latin America is not the only site for conservation victories. On August 17, 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) proposed designating 838,232 acres in southern Arizona and New Mexico as critical jaguar habitat, meaning that the areas would be protected from any activities that might “adversely modify” the land.

There has been some controversy over protecting a habitat that has seen so few jaguars in recent times. As Panthera’s Jaguar Program Executive Director, Dr. Howard Quigley explains, “Jaguars appear in the U.S. every few years now, but it’s very difficult to say whether there will ever be resident jaguars again in the U.S. The U.S. habitat is at the extreme north of the jaguar’s range, and it likely very marginal habitat for them. The greatest chance for jaguars to regularly visit or even reside in the U.S. is if the population in Sonora is stable, or increasing.”

The FWS asserts that protecting this “extreme northern” habitat is important for jaguars as a species. Peripheral populations are often more adaptable to extreme conditions and more likely to withstand droughts or other effects that may be brought about by climate change. Their evolutionary diversity greatly strengthens the gene pool and ensures the long-term potential health of the species.

The iconic and mystical jaguar (Panthera onca) is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. Currently, they face not only the threat of habitat loss and loss of natural prey, but also the threat of direct killing.

“Of the two [habitat loss and direct killing], the most pressing, daily, is the direct killing. Likely hundreds of jaguars are killed each year because they take livestock or just live in areas with livestock,” says Quigley. “We have many methods that will reduce jaguar predation on livestock and we are working hard to make ranching and jaguar habitat conservation compatible. One such method is working with local ranchers to place territorial water buffalo amongst livestock to deter jaguar attacks.”

It is clear that reviving the jaguar population will take international cooperation as well as multi-faceted, creative conservation approaches. Fortunately for the jaguars, protecting their own habitats and corridors will benefit other forms of life as well.

“This sort of connectivity provides for ecosystem resiliency and health in the face of climate change and fragmentation of habitat,” adds Quigley, “If we provide for jaguar movements through these corridors, we provide pathways for so many other organisms and processes that will benefit long-term conservation, and benefit human existence and health, too.”

The Americas’ biggest cat: the jaguar. Photo by: Steve Winter/Panthera.

Jaguar corridors. Map courtesy of Panthera. Click to enlarge.

Jaguar historic versus current range. Graph courtesy of Panthera. Click to enlarge.

Related articles

Key mammals dying off in rainforest fragments

(08/15/2012) When the Portuguese first arrived on the shores of what is now Brazil, a massive forest waited for them. Not the Amazon, but the Atlantic Forest, stretching for over 1.2 million kilometers. Here jaguars, the continent’s apex predator, stalked peccaries, while tapirs waded in rivers and giant anteaters unearthed termites mounds. Here, also, the Tupi people numbered around a million people. Now, almost all of this gone: 93 percent of the Atlantic Forest has been converted to agriculture, pasture, and cities, the bulk of it lost since the 1940s. The Tupi people are largely vanished due to slavery and disease, and, according to a new study in the open access journal PLoS ONE, so are many of the forest’s megafauna, from jaguars to giant anteaters.

Jaguars photographed in palm oil plantation

(06/06/2012) As the highly-lucrative palm oil plantation moves from Southeast Asia to Africa and Latin America, it brings with it concerns of deforestation and wildlife loss. But an ongoing study in Colombia is finding that small palm oil plantations may not significantly hurt at least one species: the jaguar. Researchers in Magdalena River Valley have taken the first ever photos of jaguars in a palm plantation, including a mother with two cubs, showing that the America’s biggest cat may not avoid palm oil plantations like its Asian relative, the tiger.

Jaguar v. sea turtle: when land and marine conservation icons collide

(05/16/2012) At first, an encounter between a jaguar (Panthera onca) and a green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) seems improbable, even ridiculous, but the two species do come into fatal contact when a female turtle, every two to four years, crawls up a jungle beach to lay her eggs. A hungry jaguar will attack the nesting turtle, killing it with a bite to the neck, and dragging the massive animal—sometime all the way into the jungle—to eat the muscles around the neck and flippers. Despite the surprising nature of such encounters, this behavior, and its impact on populations, has been little studied. Now, a new study in Costa Rica’s Tortuguero National Park has documented five years of jaguar attacks on marine turtles—and finds these encounters are not only more common than expected, but on the rise.

Animal picture of the day: rare photo of mother jaguar and cubs

(12/21/2011) A mother jaguar, named Kaaiyana by scientists, and cubs were recently photographed in Kaa Iya National Park in Bolivia. “Kaaiyana’s tolerance of observers is a testimony to the absence of hunters in this area, and her success as a mother means there is plenty of food for her and her cubs to eat,” said John Polisar, coordinator of Wildlife Conservation Society’s (WCS) Jaguar Conservation Program. WCS released the photos.