Oil palm plantation

Palm oil giant PT SMART appears to be honoring its commitment to avoid conversion of high carbon forests in Indonesian Borneo, reports a new assessment published by Greenomics, an Indonesian environmental activist group.

The report was issued 15 months after PT SMART — a subsidiary of Singapore-based Golden Agri Resources (GAR) and owned by Indonesia’s Sinarmas Group — signed a landmark agreement with The Forest Trust (TFT) to spare forests and peatlands that have more than 35 tons of carbon per hectare. The deal came after a damaging Greenpeace campaign, which targeted PT SMART for clearing orangutan habitat in Kalimantan and cost the company millions of dollars in contracts. The agreement also binds PT SMART to conservation high conservation value forests and free, prior informed consent in working with communities living in and around oil palm concessions.

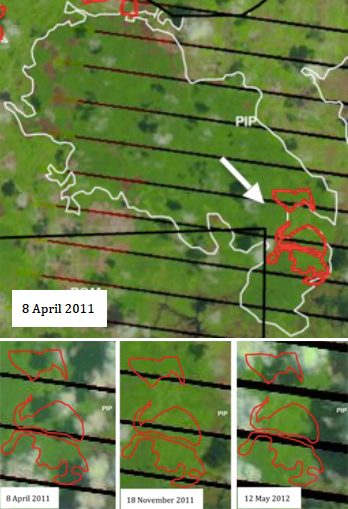

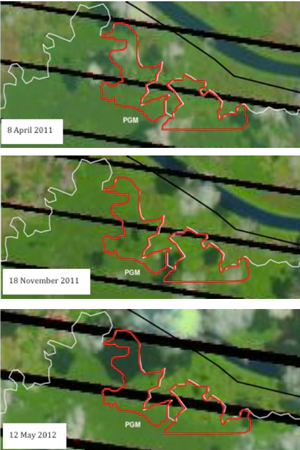

Satellite imagery showing GAR concession within a forested area. The red line signifies the boundary of timber clearing permit blocks, while the white area is the boundary of the relatively forested area on the Ministry of Forestry’s 2009/2010 land-cover data to show changes in land cover that occurred between 8 April 2011, 18 November 2011, and 12 May 2012. GAR appears to be sparing the forests as part of its forest conservation policy, according to Greenomics. |

Analyzing satellite imagery and permit data issued by the local regency, Greenomics found that three GAR companies — PT Paramitra Internusa Pratama (PIP), PT Persada Graha Mandiri (PGM), and PT Kartika Prima Cipta (KPC) — operating in Kapuas Hulu Regency have preserved three blocks of secondary peat swamp within their concessions. The forest blocks amount to 2,283 hectares of the 60,000 hectares of concessions. Under the permit, the GAR companies have approval to clear these areas but opted to instead maintain them as forest under its forest policy.

The spatial and legal analysis was accompanied by data showing that GAR had reduced its deforestation payments, indicating that land its companies cleared had low volumes of timber. Deforestation payments are based on the value of timber felled during conversion — higher values would reflect a larger volume of timber and therefore higher quality forest.

The findings are significant because until now, Greenomics had been skeptical of the GAR deal. The group nonetheless welcomed the palm oil giant’s progress in implementing its forest policy.

“It appears that concrete efforts are being made to conserve secondary swamp forest in parts of GAR’s palm concessions,” Elfian Effendi, director of Greenomics, told mongabay.com. “Great achievement has been made during the first year of GAR’s forest conservation policy implementation in the three GAR’s concession operating in West Kalimantan.”

The report was not entirely positive however. It cited violations by GAR companies in clearing “secondary swamp forest” and “swamp scrubland” outside its timber clearing permit blocks. In some cases palm oil companies also lacked the proper timber clearing permits for small areas of land that “cannot be categorized as high carbon stock forest or high conservation value forest,” according to the report.

The companies further removed more than 10,000 cubic meter of commercial trees, equal to more than 40,000 trees, some of which are listed under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). But the authorities signed off on the logging of the listed species, so the activity wasn’t illegal, says Effendi.

“The land-clearing of endangered tree species is not illegal because they are not protected by Indonesian law,” said Effendi. “However, in terms of forest conservation policy, it could raise a question, especially about the IUCN-Red List tree species that were removed from their habitat.”

Conversion of areas containing species is standard practice in Indonesia, but the report noted that Daud Dharsono, President Director of PT SMART, was receptive to the concerns raised by Greenomics.

Satellite imagery showing GAR concession within a forested area. GAR appears to be sparing the forests as part of its forest conservation policy, according to Greenomics. |

“Bearing in mind that this report criticizes GAR’s forest conservation policies during the first year of implementation, the willingness of Pak Daud to engage in transparent and constructive dialog is something that is very rarely found in Indonesian business,” the report stated. “Rather, the norm is a style of leadership that attempts to avoid or shirk engaging in dialog with critics. For that reason, Greenomics Indonesia feels it appropriate to give praise where praise is due.”

“Greenomics Indonesia believes that in the second year of GAR’s forest conservation policy in West Kalimantan, its implementation may be characterized as best practice that should be followed as part of the effort to reduce the carbon footprint and level of deforestation associated with the development of palm oil plantations in Indonesia.”

GAR declined to comment directly on the report, noting that its own assessment is forthcoming, but Daud told mongabay.com that multi-stakeholder engagement is important to the process.

“The High Carbon Stock (HCS) forest fieldwork under GAR’s Forest Conservation Policy was conducted by GAR, The Forest Trust and NGOs including Greenpeace. This fieldwork has been completed as planned,” wrote Daud via email.

“The team is currently finalizing the HCS fieldwork report and will require time to ensure this is well documented. The team will be engaging with multi-stakeholders to discuss these findings. We believe that it is important for multi-stakeholders to come together to find solutions to conserve the forests, create much needed employment and ensure long-term growth of the palm oil industry which is a vital part of the Indonesian economy.”

Indonesia is the world’d largest palm oil producer. Palm oil is the highest yielding of commercial oilseeds yet its expansion at the expense of rainforests and carbon-dense peatlands in recent decades have made it the target of activist campaigns. The industry has responded by developing the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a certification standard that aims to reduce the environmental impact of production.

CITATION: Greenomics: What has been learned from first year of Golden Agri’s forest conservation policy in West Kalimantan? (May 2012)

Related articles

Pro-deforestation group criticizes palm oil giant for sustainability pact

(03/24/2011) World Growth International, a group that advocates on behalf of industrial forestry interests, has criticized Golden Agri Resources (GAR), Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer, for signing a forest policy that aims to protect high conservation value and high carbon stock forest and requires free, prior informed consent (FPIC) in working with communities potentially affected by oil palm development. In a newsletter published March 10, World Growth International claimed that GAR’s agreement “could severely hamper the company’s growth” by limiting where it can establish new plantations and says that negotiating with multiple stakeholders “will delay and complicate any investment by the company.” World Growth International concludes by implying that GAR may renege on its commitment. But Peter Heng, Managing Director, Communications and Sustainability at GAR, disagreed with World Growth International’s assessment.

Breakthrough? Controversial palm oil company signs rainforest pact

(02/09/2011) One of the world’s highest profile and most controversial palm oil companies, Golden Agri-Resources Limited (GAR), has signed an agreement committing it to protect tropical forests and peatlands in Indonesia. The deal—signed with The Forest Trust, an environmental group that works with companies to improve their supply chains—could have significant ramifications for how palm oil is produced in the country, which is the world’s largest producer of palm oil.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?