Despite being a strong La Niña year, which tends to be cooler than the average year, 2011 was the ninth warmest year on record and the warmest La Niña yet, according to a global temperature analysis by NASA. To date, nine of the world’s ten warmest years have occurred since 2000 according to data going back to 1880.

“We know the planet is absorbing more energy than it is emitting,” said NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) Director James Hansen in a press release. “So we are continuing to see a trend toward higher temperatures. Even with the cooling effects of a strong La Niña influence and low solar activity for the past several years, 2011 was one of the 10 warmest years on record.”

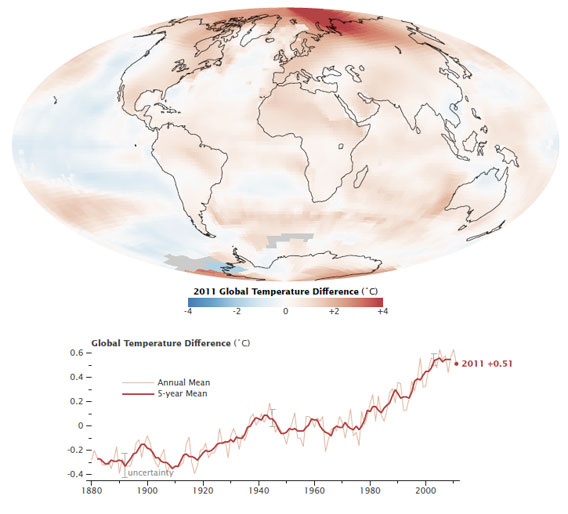

The global temperature in 2011 was 0.92 degrees Fahrenheit (0.51 Celsius) degrees warmer than a mid-20th Century baseline. Scientists don’t expect every year to be warmer than the last due to climate change, but they do expect to see a warming trend over decades, which has been the case: 2000-2009 was the warmest decade yet on record.

Climate change is caused by human activities that emit greenhouse gases including burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and certain agricultural practices among others. The carbon dioxide level in the atmosphere is currently 390 parts per million, over a hundred parts per million higher than in 1880.

The effects of on-going heat are being felt far-and-wide. Last year saw the Arctic’s sea ice hit its lowest volume on record and its second lowest extent. Ice shelves in Canada have halved in the last six years. Meanwhile, with wider recognition of the impacts of climate change on severe weather, this year was also notable for an unusually large amount of extreme weather events. For example, 2011 saw drought and famine in East Africa, killing over tens-of-thousands of people; massive floods in Asia and the Americas with a record-breaking deluge in Thailand, dubbed its worst natural disaster in history; a wide-variety of extreme weather events in the US, including an extended drought and heatwave in Texas; as well as a below-average year for tropical cyclones.

Hansen says he expects an El Niño year soon. The counterpart of La Niña, El Niño usually brings warmer temperatures worldwide.

“It’s always dangerous to make predictions about El Niño, but it’s safe to say we’ll see one in the next three years,” Hansen said. “It won’t take a very strong El Niño to push temperatures above 2010.”

The NOAA recently announced that 2011 was the eleventh warmest year on record, while the UN World Meteorological Organization (WMO) predicted it would be the tenth warmest on record. Slight differences in these records are based on different analysis.

Map shows how much warmer or cooler each region was in 2011 compared with an averaged “base period” from 1951–1980. The line plot shows yearly temperature variations (from the base period average) for every year from 1880 to now. Image by: NASA.

Related articles

Deforestation, climate change threaten the ecological resilience of the Amazon rainforest

(01/19/2012) The combination of deforestation, forest degradation, and the effects of climate change are weakening the resilience of the Amazon rainforest ecosystem, potentially leading to loss of carbon storage and changes in rainfall patterns and river discharge, finds a comprehensive review published in the journal Nature.

Targeting methane, black carbon could buy world a little time on climate change

(01/12/2012) A new study in Science argues that reducing methane and black carbon emissions would bring global health, agriculture, and climate benefits. While such reductions would not replace the need to reduce CO2 emissions, they could have the result of lowering global temperature by 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit) by mid-century, as well as having the added benefits of saving lives and boosting agricultural yields. In addition, the authors contend that dealing with black carbon and methane now would be inexpensive and politically feasible.

Seals, birds, and alpine plants suffer under climate change

(01/11/2012) The number of species identified by scientists as vulnerable to climate change continues to rise along with the Earth’s temperature. Recent studies have found that a warmer world is leading to premature deaths of harp seal pups (Pagophilus groenlandicus) in the Arctic, a decline of some duck species in Canada, shrinking alpine meadows in Europe, and indirect pressure on mountain songbirds and plants in the U.S. Scientists have long known that climate change will upend ecosystems worldwide, creating climate winners and losers, and likely leading to waves of extinction. While the impacts of climate change on polar bears and coral reefs have been well-documented, every year scientists add new species to the list of those already threatened by anthropogenic climate change.