Lack of clarity makes it difficult to assess whether Indonesia’s moratorium on new logging concessions in primary forest areas and peatlands will actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation, according to a new comprehensive assessment [PDF] of the instruction issued last week by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

The analysis, conducted by Philip Wells and Gary Paoli of Indonesia-based Daemeter Consulting, concludes that while the moratorium is “potentially a powerful instrument” for achieving the Indonesian president’s goals of 7 percent annual growth and a 26 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from a projected 2020 baseline, the language of the moratorium leaves significant areas open for interpretation, potentially offering loopholes for developers.

Wells and Paoli note that the new permit restrictions are limited to areas denoted on a map released in the presidential instruction (Inpres) [Indonesian | English]. But the data and assumptions underlying the map’s production aren’t clear in some cases. For example, the instruction doesn’t explain how “primary forest” areas are designated in the map. The authors say the primary forest element of the map appears to be based on an unreleased interpretation of 2009 satellite imagery by the Ministry of Forestry, minus areas that have already been concessioned for logging and conversion, as well as “some but not all Conservation Areas.” The amount of primary forest presently allocated in concessions is not specified by the Ministry of Forestry or the Inpres.

The analysis highlights an apparent inconsistency between the Letter of Intent (LOI) Indonesia signed with Norway, which lays out a plan for reducing deforestation, and the Indonesian government.

“The LoI, which serves as the proximal motivation for the presidential instruction, uses the term ‘natural forest’ in reference to areas intended to be covered by the moratorium,” Wells and Paoli write. “Within

the presidential instruction, the government of Indonesia has elected to interpret ‘natural forest’ as forest that has never been logged or damaged by humans. This narrow GoI definition of natural forest is roughly equivalent to undisturbed primary forest in the common nomenclature used by the wider public, and as such may not conform to expectations of all parties concerning the LoI.”

The exclusion of secondary forest from the moratorium has implications for the effort to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation. Selectively logged forests can sequester substantial amounts of carbon and therefore their conversion can produce upwards of 100 metric tons of carbon per hectare. Wells and Paoli thus note that “future conversion of logged forest will therefore continue to be a major source of emissions for Indonesia” under the moratorium. They estimate that “the total area of forest covered [by the moratorium] is far less than the total area that is not” and note that “an arbitrary portion of official conservation areas and protected forests appear to have been excluded.”

The map has also yet to be released in a format that allows for closer scrutiny. The public version has a resolution of 1:19 million, too coarse for meaningful use.

In their analysis, Wells and Paoli reveal another complication: potential inconsistencies between the map and spirit of the Inpres.

“The Second Dictum of the PI states that the moratorium applies to primary natural forest and peat lands, without making explicit reference to the Map. However, in practice, the moratorium on issuance on new licenses applies to all areas covered by the Map,” the write. “This raises the question, what happens when there are discrepancies between the Map itself and areas the text of the PI mandates should depicted in the Map? No instructions have been provided in the text to address this point.”

|

Nor does the Inpres seem to address a potential loophole: expansion of existing plantation licenses into primary forest areas. An ministerial decree issued December 31, 2010 — the day before the moratorium was set to take effect — allows the conversion of industrial plantation licenses (HTI permit) into logging licenses (HPH). Once logged, the forest would no longer be considered “primary” so it would be escape the moratorium.

Given the uncertainty of Inpres at the national level, Wells and Paoli highlight the need to improve planning at sub-national levels and within areas classified as “non-forest lands” that may indeed have forest cover but are outside the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Forestry.

The Inpres defines a few potentially large exemptions from the moratorium: licenses for geothermal projects, oil and gas development, and electricity generation are excluded, indicating these activities can continue in primary forest areas and peatlands. Rice fields and sugarcane plantations can also be carved out of forest areas otherwise banned from conversion under the moratorium, opening the door for a massive agricultural development project planned for Papua to proceed.

Wells and Paoli end their analysis by emphasizing the uncertainty of the moratorium as defined by the Inpres.

“The magnitude of potential GHG emission deferrals likely to result from the presidential instruction as written, or that could have been deferred under alternative scenarios put forward for the moratorium (e.g. by the REDD+ Taskforce), is not possible to estimate with any precision,” they write.

-

The long-awaited PI is envisaged to function as a cornerstone of Indonesia’s emerging policy reform efforts to place the economy on a path toward sustainable low emissions development [7 percent growth/26 percent GHG reduction]. As written, the PI on its own appears unlikely to guarantee the full range of fundamental changes to planning, coordination and transparency required to achieve 7/26. It is, nevertheless, an unprecedented, positive step forward with potential to be improved and strengthened significantly in the coming months. The PI must be viewed not in isolation, but rather as one part of a larger set of national and sub-national initiatives blending public sector leadership with private sector support and civil society participation to reform land use planning and forest management in Indonesia. Significant challenges lie ahead for implementation, but the PI lays out a vision and foundation for moving forward in a coordinated fashion to invigorate the process of reform underway.

An Analysis of Presidential Instruction No. 10, 2011: Moratorium on Granting of New Licenses and Improvement of Natural Primary Forest and Peatland Governance [PDF] [Indonesian version]

Related articles

Indonesia’s moratorium allows mining in protected forests

(05/23/2011) Indonesia’s mining industry expects the just implemented moratorium on new forestry concessions in primary forests and peatlands to open up protected areas to underground coal and gold mining, reports the Jakarta Globe.

Indonesia’s moratorium disappoints environmentalists

(05/20/2011) The moratorium on permits for new concessions in primary rainforests and peatlands will have a limited impact in reducing deforestation in Indonesia, say environmentalists who have reviewed the instruction released today by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The moratorium, which took effect January 1, 2011, but had yet to be defined until today’s presidential decree, aims to slow Indonesia’s deforestation rate, which is among the highest in the world. Indonesia agreed to establish the moratorium as part of its reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) agreement with Norway. Under the pact, Norway will provide up to a billion dollars in funds contingent on Indonesia’s success in curtailing destruction of carbon-dense forests and peatlands.

Indonesia signs moratorium on new permits for logging, palm oil concessions

(05/19/2011) After five-and-a-half months of delay due to political infighting, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono finally signed a two-year moratorium on the granting of new permits to clear rainforests and peatlands, reports Reuters.

Is Indonesia losing its most valuable assets?

(05/16/2011) Deep in the rainforests of Malaysian Borneo in the late 1980s, researchers made an incredible discovery: the bark of a species of peat swamp tree yielded an extract with potent anti-HIV activity. An anti-HIV drug made from the compound is now nearing clinical trials. It could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year and help improve the lives of millions of people. This story is significant for Indonesia because its forests house a similar species. In fact, Indonesia’s forests probably contain many other potentially valuable species, although our understanding of these is poor. Given Indonesia’s biological richness — Indonesia has the highest number of plant and animal species of any country on the planet — shouldn’t policymakers and businesses be giving priority to protecting and understanding rainforests, peatlands, mountains, coral reefs, and mangrove ecosystems, rather than destroying them for commodities?

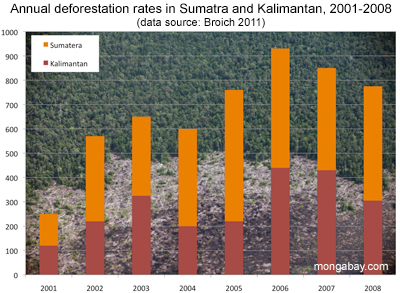

Election cycle linked to deforestation rate in Indonesia

(04/14/2011) Increased fragmentation of political jurisdictions and the election cycle contribute to Indonesia’s high deforestation rate according to analysis published by researchers at the London School of Economics (LSE), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and South Dakota State University (SDSU). The research confirms the observation that Indonesian politicians in forest-rich districts seem repay their election debts by granting forest concessions.

Indonesia can meet low carbon goals without sacrificing economic growth, says UK report

(04/14/2011) Indonesia can meet its low carbon development goals without sacrificing economic growth, reports an assessment commissioned by the British government.

Pulp and paper firms urged to save 1.2M ha of forest slated for clearing in Indonesia

(03/17/2011) Indonesian environmental groups launched a urgent plea urging the country’s two largest pulp and paper companies not to clear 800,000 hectares of forest and peatland in their concessions in Sumatra. Eyes on the Forest, a coalition of Indonesian NGOs, released maps showing that Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) control blocks of land representing 31 percent of the remaining forest in the province of Riau, one of Sumatra’s most forested provinces. Much of the forest lies on deep peat, which releases large of amount of carbon when drained and cleared for timber plantations.

Fighting illegal logging in Indonesia by giving communities a stake in forest management

(03/10/2011) Over the past twenty years Indonesia lost more than 24 million hectares of forest, an area larger than the U.K. Much of the deforestation was driven by logging for overseas markets. According to the World Bank, a substantial proportion of this logging was illegal. Curtailing illegal logging may seem relatively simple, but at the root of the problem of illegal logging is something bigger: Indonesia’s land policy. Can the tide be turned? There are signs it can. Indonesia is beginning to see a shift back toward traditional models of forest management in some areas. Where it is happening, forests are recovering. Telapak understands the issue well. It is pushing community logging as the ‘new’ forest management regime in Indonesia. Telapak sees community forest management as a way to combat illegal logging while creating sustainable livelihoods.

Pulp plantations destroying Sumatra’s rainforests

(11/30/2010) Indonesia’s push to become the world’s largest supplier of palm oil and a major pulp and paper exporter has taken a heavy toll on the rainforests and peatlands of Sumatra, reveals a new assessment of the island’s forest cover by WWF. The assessment, based on analysis of satellite imagery, shows Sumatra has lost nearly half of its natural forest cover since 1985. The island’s forests were cleared and converted at a rate of 542,000 hectares, or 2.1 percent, per year. More than 80 percent of forest loss occurred in lowland areas, where the most biodiverse and carbon-dense ecosystems are found.

Indonesia’s forest protection plan at risk, says report

(11/25/2010) Industrial interests are threatening to undermine Norway’s billion dollar partnership with Indonesia, potentially turning the forest conservation deal into a scheme that subsidizes conversion of rainforests and peatlands for oil palm and pulp and paper plantations, logging concessions, and energy production, claims a new report from Greenpeace.

Indonesia’s forest conservation plan may not sufficiently reduce emissions

(08/25/2010) One third of Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation originate from areas not officially defined as ‘forest’ suggesting that efforts to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD+) may fail unless they account for carbon across the country’s entire landscape, warns a new report published by the World Agroforestry Centre (CGIAR). The policy brief finds that up to 600 million tons of Indonesia’s carbon emissions ‘occur outside institutionally defined forests’ and are therefore not accounted for under the current national REDD+ policy, which, if implemented, would enable Indonesia to win compensation from industrialized countries for protecting its carbon-dense forests and peatlands as a climate change mechanism.

Indonesia’s plan to save its rainforests

(06/14/2010) Late last year Indonesia made global headlines with a bold pledge to reduce deforestation, which claimed nearly 28 million hectares (108,000 square miles) of forest between 1990 and 2005 and is the source of about 80 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said Indonesia would voluntarily cut emissions 26 percent — and up to 41 percent with sufficient international support — from a projected baseline by 2020. Last month, Indonesia began to finally detail its plan, which includes a two-year moratorium on new forestry concession on rainforest lands and peat swamps and will be supported over the next five years by a one billion dollar contribution by Norway, under the Scandinavian nation’s International Climate and Forests Initiative. In an interview with mongabay.com, Agus Purnomo and Yani Saloh of Indonesia’s National Climate Change Council to the President discussed the new forest program and Norway’s billion dollar commitment.

Indonesia announces moratorium on granting new forest concessions

(05/28/2010) With one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emissions due mostly to forest loss, and with a rich biodiversity that is fighting to survive amid large-scale habitat loss, Indonesia today announced a deal that may be the beginning of stopping forest loss in the Southeast Asian country. Indonesia announced a two year moratorium on granting new concessions of rainforest and peat forest for clearing in Oslo, Norway, however concessions already granted to companies will not be stopped. The announcement came as Indonesia received 1 billion US dollars from Norway to help the country stop deforestation.

Norway to provide Indonesia with $1 billion to protect rainforests

(05/19/2010) Norway will provide up to $1 billion to Indonesia to help reduce deforestation and forest degradation, reports The Jakarta Post.