The moratorium on permits for new concessions in primary rainforests and peatlands will have a limited impact in reducing deforestation in Indonesia, say environmentalists who have reviewed the instruction [PDF in Indonesian] released today by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

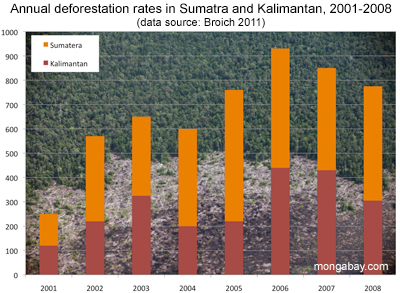

The moratorium, which took effect January 1, 2011, but had yet to be defined until today’s presidential decree, aims to slow Indonesia’s deforestation rate, which is among the highest in the world. Indonesia agreed to establish the moratorium as part of its reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) agreement with Norway. Under the pact, Norway will provide up to a billion dollars in funds contingent on Indonesia’s success in curtailing destruction of carbon-dense forests and peatlands.

The delay in defining the measure was the result of intense lobbying by forestry interests — including oil palm developers, pulp and paper companies, logging firms, and the agroindustrial, mining, and energy sectors — that feared losing access to forest lands. The language of the presidential indicates that they were successful in their battle to narrowly define the moratorium, which includes only peatlands and virgin forests. Secondary forests, as well as primary forests and peatlands that have already been granted as concessions, will be exempt from the moratorium.

The delay in defining the moratorium also reflected a power struggle between the Ministry of Forestry, which controls the concession process and has been the source of incredible corruption, and the special REDD+ Task Force headed by Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, an official lauded for his staunch anti-corruption stance. |

In total, the Indonesian government estimates that 64 million hectares of primary forests and peatlands — roughly 35 million of which are already protected — will be off-limits to concessions through December 31, 2012. Greenpeace says that roughly 40 million hectares of Indonesian forest are left open for deforestation under the moratorium.

“Millions of hectares of forests will still be destroyed. And most of the areas included on the map are already protected, so the moratorium offers ‘little’ extra,” Bustar Maitar of Greenpeace Southeast Asia said in a statement. “In the forests, large scale destruction will continue as usual. This announcement is a long way from the Indonesian President’s commitment to protect Indonesia forests.”

“Most of the remaining forest areas in Indonesia are actually secondary forests,” said Wetlands International in a statement. “Millions of hectares of the Indonesian forests may still be converted.”

Some environmentalists had hoped the decree would be more broadly defined, using carbon storage or conservation value as a bar for excluding forests from new concessions. Those measures would have protected selectively logged forest that serves as habitat for endangered species like orangutans, rhinos, tigers, and elephants. Instead the moratorium will allow these areas — amounting to 36 million hectares according to the Ministry of Forestry — to be logged and converted to plantations. Furthermore, because the measure is the form of a presidential instruction, it is not legally binding.

|

“Ministers and state officials could, in theory, violate or ignore the presidential sanction without incurring legal sanctions,” said an observer who asked not to be identified.

But Dipo Alam, Cabinet Secretary for President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, disagreed.

“There will be legal sanctions for those who do not obey the INPRES,” he told mongabay.com. “Law enforcement will be applied.”

Other loopholes under the moratorium also raise concerns. Due to food and energy security concerns, the moratorium grants exemptions for rice, sugar, geothermal, and oil and gas projects. Therefore a massive agricultural project planned on forest lands in Indonesian New Guinea will proceed.

“This is a bitter disappointment. It will do little to protect Indonesia’s forests and peatlands,” Paul Winn of Greenpeace Australia-Pacific told Reuters. “Seventy-five percent of the forests purportedly protected by this moratorium are already protected under existing Indonesian law, and the numerous exemptions further erode any environmental benefits.”

Reason for optimism?

But while there were reservations over the details of the moratorium, environmentalists and scientists expressed hope that it could at least represent a symbolic political step toward better protection and management of Indonesia’s forests.

Clearing of peatland in Central Kalimantan

Is Indonesia losing its most valuable assets? Will Indonesia’s big REDD rainforest deal work? (12/28/2010) Flying in a plane over the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, rainforest stretches like a sea of green, broken only by rugged mountain ranges and winding rivers. The broccoli-like canopy shows little sign of human influence. But as you near Jayapura, the provincial capital of Papua, the tree cover becomes patchier—a sign of logging—and red scars from mining appear before giving way to the monotonous dark green of oil palm plantations and finally grasslands and urban areas. The scene is not unique to Indonesian New Guinea; it has been repeated across the world’s largest archipelago for decades, partly a consequence of agricultural expansion by small farmers, but increasingly a product of extractive industries, especially the logging, plantation, and mining sectors. Papua, in fact, is Indonesia’s last frontier and therefore represents two diverging options for the country’s development path: continued deforestation and degradation of forests under a business-as-usual approach or a shift toward a fundamentally different and unproven model based on greater transparency and careful stewardship of its forest resources. |

“This moratorium represents an important political shift towards protecting our forests,” said Greenpeace’s Maitar.

“This is a positive development,” added Daniel Murdiyarso, a scientist at the Indonesia-based forest research institute CIFOR. “This will see a large area of natural forest protected from being cleared and it will help preserve the country’s carbon-rich peatlands.”

Slowing conversion of peatlands and forests will be critical if Indonesia aims to meet its commitment to reduce carbon dioxide emissions 26-41 percent from a projected 2020 baseline. The country is presently the third largest greenhouse gas emitter after China and the United States. Roughly 80 percent of its emissions result from degradation of peatlands and deforestation.

The hope is that the moratorium could help Indonesia transition toward a greener development path by pushing wood-pulp and oil palm plantation expansion to less sensitive areas, including deforested grassland and heavily degraded scrub, which cover millions of hectares of land, but haven’t been developed to due social conflict and lack of economic incentives.

“This moratorium can now help to shift these sectors to degraded areas with mineral soils,” said Marcel Silvius of Wetlands International.

But while Indonesia’s palm oil industry, which has lately been battered by criticism that it drives deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions, could see a boost in some markets if companies voluntarily stop converting forests for new plantations, it seems unlikely that most would do so. However there may be exceptions. For example, PT Smart, Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer, recently adopted a forest policy that goes beyond what is established under the moratorium. The policy, which came in response to a Greenpeace campaign that caused the firm to lose tens of millions of dollars in business due to concerns over deforestation, prohibits conversion of peatlands and high conservation value forests and requires free, prior, and informed consent from communities.

Accordingly, SMART Director Pak Daud Dharsono, said his company supports the moratorium.

“In line with our sustainability commitment, SMART supports the two-year moratorium,” he told mongabay.com. “This initiative will enhance SMART’s own efforts in preserving primary forests, peat land and protecting biodiversity in Indonesia.”

“The two-year moratorium is an opportunity to review and strengthen Indonesia’s policies such as land reconciliation and GHG measurements.”

Nevertheless, Agus Purnomo, the Indonesian president’s special adviser on climate change, seemed to indicate the palm oil industry could proceed on a mostly business-as-usual path under the moratorium.

“There is no limitation for those who want to develop business-based plantations,” he was quoted as saying by Reuters. “We are not banning firms for palm oil expansion. We are just advising them to do so on secondary forests.”

Opportunity for reform

Supporters of the Indonesia’s REDD program say it could help set in motion much-needed governance reform, including helping root out corruption and harmonizing policy between different agencies and levels of government. Currently there are inconsistencies in the way concessions are distributed, laws are enforced, and existing land use is recognized by the state, creating opportunities for graft and mismanagement.

The presidential instruction on the moratorium aims to streamline forest policy by assigning coordination and oversight responsibilities to a single agency: the President’s REDD+ Taskforce.

“Up until now, insufficient data and lack of coordination between the national, provincial and district authorities has meant that Indonesia’s land management, from spatial planning to issuance and enforcement of permits has been chaotic, and the Presidential Instruction allows us the breathing space to get it right.” said Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, Head of the President’s Delivery Unit for Development Monitoring and Oversight and Chair of the REDD+ Taskforce, in a statement.

Kuntoro’s Taskforce says the moratorium will create a window for reform.

“The suspension gives opportunity to improve forest governance by reviewing and refining the regulatory framework for land use permits and establishing a database system with in‐depth information on degraded land that enhances spatial planning, clearly designate land for development, and support companies that move into degraded land,” continued the statement from the REDD+ Taskforce. “The two‐year suspension gives time to improve agricultural productivity, solve land tenure issues related to overlapping concessions and the rights of local communities, strengthen enforcement of sustainable logging and mining practices, reduce illegal logging and decrease the clearing of land through fires.”

Related articles

Losses from deforestation top $36 billion in Indonesian Borneo

(04/29/2011) Illegal forest conversion by mining and plantation companies in Indonesian Borneo has cost the state $36 billion according to a Forest Ministry official.

Indonesian official: REDD+ forest conservation plan need not limit growth of palm oil industry

(04/29/2011) Indonesia’s low carbon development strategy will not impede the palm oil industry’s growth said a key Indonesian climate official during a meeting with leaders from the country’s palm oil industry. During a meeting on Thursday, Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, head of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s REDD+ Task Force, asked industry leaders for their input on the government’s effort to shift oil palm expansion to degraded non-forest land.

Election cycle linked to deforestation rate in Indonesia

(04/14/2011) Increased fragmentation of political jurisdictions and the election cycle contribute to Indonesia’s high deforestation rate according to analysis published by researchers at the London School of Economics (LSE), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and South Dakota State University (SDSU). The research confirms the observation that Indonesian politicians in forest-rich districts seem repay their election debts by granting forest concessions.

Indonesia can meet low carbon goals without sacrificing economic growth, says UK report

(04/14/2011) Indonesia can meet its low carbon development goals without sacrificing economic growth, reports an assessment commissioned by the British government.

Pulp and paper firms urged to save 1.2M ha of forest slated for clearing in Indonesia

(03/17/2011) Indonesian environmental groups launched a urgent plea urging the country’s two largest pulp and paper companies not to clear 800,000 hectares of forest and peatland in their concessions in Sumatra. Eyes on the Forest, a coalition of Indonesian NGOs, released maps showing that Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) control blocks of land representing 31 percent of the remaining forest in the province of Riau, one of Sumatra’s most forested provinces. Much of the forest lies on deep peat, which releases large of amount of carbon when drained and cleared for timber plantations.

Fighting illegal logging in Indonesia by giving communities a stake in forest management

(03/10/2011) Over the past twenty years Indonesia lost more than 24 million hectares of forest, an area larger than the U.K. Much of the deforestation was driven by logging for overseas markets. According to the World Bank, a substantial proportion of this logging was illegal. Curtailing illegal logging may seem relatively simple, but at the root of the problem of illegal logging is something bigger: Indonesia’s land policy. Can the tide be turned? There are signs it can. Indonesia is beginning to see a shift back toward traditional models of forest management in some areas. Where it is happening, forests are recovering. Telapak understands the issue well. It is pushing community logging as the ‘new’ forest management regime in Indonesia. Telapak sees community forest management as a way to combat illegal logging while creating sustainable livelihoods.

Breakthrough? Controversial palm oil company signs rainforest pact

(02/09/2011) One of the world’s highest profile and most controversial palm oil companies, Golden Agri-Resources Limited (GAR), has signed an agreement committing it to protect tropical forests and peatlands in Indonesia. The deal—signed with The Forest Trust, an environmental group that works with companies to improve their supply chains—could have significant ramifications for how palm oil is produced in the country, which is the world’s largest producer of palm oil.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Indonesia grants slew of last-minute logging concessions on eve of moratorium

(01/25/2011) Indonesia’s Minister of Forestry granted nearly 3 million hectares of plantation forestry concessions the day before the country’s president was due to sign a decree establishing a two-year moratorium on new logging licenses, reports a new analysis by Greenomics, an Indonesian environmental group.

Indonesia to open protected forests to geothermal power

(01/14/2011) The Indonesian government will soon issue a decree allowing geothermal mining in protected forests, reports The Jakarta Post.

Does chopping down rainforests for pulp and paper help alleviate poverty in Indonesia?

(01/13/2011) Over the past several years, Asia Pulp & Paper has engaged in a marketing campaign to represent its operations in Sumatra as socially and environmentally sustainable. APP and its agents maintain that industrial pulp and paper production — as practiced in Sumatra — does not result in deforestation, is carbon neutral, helps protect wildlife, and alleviates poverty. While a series of analyses and reports have shown most of these assertions to be false, the final claim has largely not been contested. But is conversion of lowland rainforests for pulp and paper really in Indonesia’s best economic interest?

Indonesia delays logging moratorium

(01/05/2011) Bureaucratic confusion has led Indonesia to delay implementation of its two-year moratorium on new logging and plantation concessions in forest areas and peatlands, reports the Jakarta Globe.

Converting palm oil companies from forest destroyers into forest protectors

(01/02/2011) In efforts to save the world’s remaining rainforests great hopes have been pinned on “degraded lands” — deforested lands that are presently sitting idle in tropical countries. Optimists say shifting agriculture to such lands will help humanity produce enough food to meet growing demand without sacrificing forests and biodiversity and exacerbating social conflict. But to date, degraded lands remain an enigma, especially in Indonesia, where deforestation continues at a rapid pace. Degraded lands are often misclassified by various Indonesian ministries—land in a far-off province may be listed as “wasteland” by Jakarta, but in reality is blanked by verdant forest that sequesters carbon, houses wildlife, and affords communities with food, water, and other essentials. Granting logging and plantation concessions on these lands can result in conflict and environmental degradation.

Pulp plantations destroying Sumatra’s rainforests

(11/30/2010) Indonesia’s push to become the world’s largest supplier of palm oil and a major pulp and paper exporter has taken a heavy toll on the rainforests and peatlands of Sumatra, reveals a new assessment of the island’s forest cover by WWF. The assessment, based on analysis of satellite imagery, shows Sumatra has lost nearly half of its natural forest cover since 1985. The island’s forests were cleared and converted at a rate of 542,000 hectares, or 2.1 percent, per year. More than 80 percent of forest loss occurred in lowland areas, where the most biodiverse and carbon-dense ecosystems are found.

Plantations on peatlands are huge source of carbon emissions

(11/29/2010) Converting peatlands for wood-pulp and oil palm plantations generates nearly 1,500 tons of carbon dioxide per hectare, making these ostensibly “green” sources of paper, vegetable oil and biofuels important drivers of climate change, reports new research published by scientists at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Indonesia’s forest protection plan at risk, says report

(11/25/2010) Industrial interests are threatening to undermine Norway’s billion dollar partnership with Indonesia, potentially turning the forest conservation deal into a scheme that subsidizes conversion of rainforests and peatlands for oil palm and pulp and paper plantations, logging concessions, and energy production, claims a new report from Greenpeace.

Indonesia’s forest conservation plan may not sufficiently reduce emissions

(08/25/2010) One third of Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation originate from areas not officially defined as ‘forest’ suggesting that efforts to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD+) may fail unless they account for carbon across the country’s entire landscape, warns a new report published by the World Agroforestry Centre (CGIAR). The policy brief finds that up to 600 million tons of Indonesia’s carbon emissions ‘occur outside institutionally defined forests’ and are therefore not accounted for under the current national REDD+ policy, which, if implemented, would enable Indonesia to win compensation from industrialized countries for protecting its carbon-dense forests and peatlands as a climate change mechanism.

Indonesia’s plan to save its rainforests

(06/14/2010) Late last year Indonesia made global headlines with a bold pledge to reduce deforestation, which claimed nearly 28 million hectares (108,000 square miles) of forest between 1990 and 2005 and is the source of about 80 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said Indonesia would voluntarily cut emissions 26 percent — and up to 41 percent with sufficient international support — from a projected baseline by 2020. Last month, Indonesia began to finally detail its plan, which includes a two-year moratorium on new forestry concession on rainforest lands and peat swamps and will be supported over the next five years by a one billion dollar contribution by Norway, under the Scandinavian nation’s International Climate and Forests Initiative. In an interview with mongabay.com, Agus Purnomo and Yani Saloh of Indonesia’s National Climate Change Council to the President discussed the new forest program and Norway’s billion dollar commitment.

Indonesia announces moratorium on granting new forest concessions

(05/28/2010) With one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emissions due mostly to forest loss, and with a rich biodiversity that is fighting to survive amid large-scale habitat loss, Indonesia today announced a deal that may be the beginning of stopping forest loss in the Southeast Asian country. Indonesia announced a two year moratorium on granting new concessions of rainforest and peat forest for clearing in Oslo, Norway, however concessions already granted to companies will not be stopped. The announcement came as Indonesia received 1 billion US dollars from Norway to help the country stop deforestation.

Norway to provide Indonesia with $1 billion to protect rainforests

(05/19/2010) Norway will provide up to $1 billion to Indonesia to help reduce deforestation and forest degradation, reports The Jakarta Post.