A plan to create a pan-tropical map of forest cover and carbon stocks is moving ahead with data now available on Google Earth, reports the Woods Hole Research Center.

The project, which uses cloud-penetrating radar to assess forest cover and structure, is part of an effort to provide a means to monitor and report deforestation, a critical component of the REDD mechanism, which aims to compensate tropical countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation.

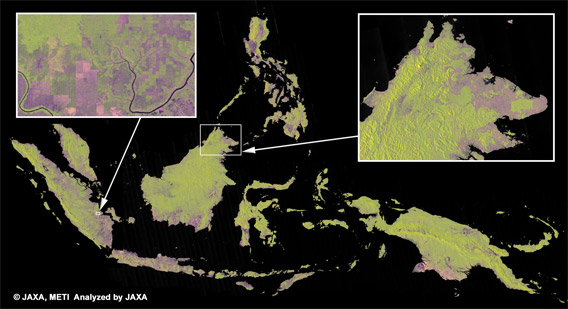

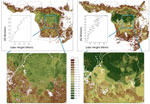

The project uses data from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) ALOS satellite, which is equipped with a radar sensor known as PALSAR. Data from NASA’s MODIS (optical) and ICESat/GLAS (lidar) sensors is also used.

Josef Kellndorfer, an associate scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, has worked extensively with radar sensor technology like that found on ALOS and says the project captures data that can be used to construct maps of global tropical forest cover on an annual basis. These maps can be used to establish a credible baseline for REDD initiatives.

“The PALSAR sensor proves as a very powerful system ready for deforestation monitoring,” he told mongabay.com. “[It] will enable us to build a data record of forest cover on an annual basis no matter what the cloud conditions are. We can even see through haze and smoke caused by forest fires.”

José Achache, Executive Director of the Group on Earth Observations (GEO), a group that counts Google.org, Woods Hole, and NASA among its roster of members, said the work would help its efforts to develop a forest carbon tracking system.

“Satellite observations will be key to measure trends in forest carbon. We are impressed by the Woods Hole Research Center’s work, in partnership with JAXA and NASA. Systematically generated data sets such as the present pan-tropical compilation will significantly strengthen national forest tracking capabilities.”

The datasets can be viewed on the GEO-Forest Carbon Tracking Portal.

Related articles

Google Earth to monitor deforestation

(12/10/2009) It what could be a critical development in helping tropical countries monitor deforestation, Google has unveiled a partnership with scientists using advanced remote sensing technology to rapidly analyze and map forest cover in extremely high resolution. The effort could help countries detect deforestation shortly after it occurs making it easier to prevent further forest clearing.

(11/29/2009) A new handbook lays out the methodology for cultural mapping, providing indigenous groups with a powerful tool for defending their land and culture, while enabling them to benefit from some 21st century advancements. Cultural mapping may also facilitate indigenous efforts to win recognition and compensation under a proposed scheme to mitigate climate change through forest conservation. The scheme—known as REDD for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation—will be a central topic of discussion at next month’s climate talks in Copenhagen, but concerns remain that it could fail to deliver benefits to forest dwellers.

How satellites are used in conservation

(04/13/2009) In October 2008 scientists with the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew discovered a host of previously unknown species in a remote highland forest in Mozambique. The find was no accident: three years earlier, conservationist Julian Bayliss identified the site—Mount Mabu—using Google Earth, a tool that’s rapidly becoming a critical part of conservation efforts around the world. As the discovery in Mozambique suggests, remote sensing is being used for a bewildering array of applications, from monitoring sea ice to detecting deforestation to tracking wildlife. The number of uses grows as the technology matures and becomes more widely available. Google Earth may represent a critical point, bringing the power of remote sensing to the masses and allowing anyone with an Internet connection to attach data to a geographic representation of Earth.

(03/29/2009) Given that deforestation accounts for nearly one fifth of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, reducing forest clearing and degradation is increasingly seen as an critical component to any framework addressing climate change. By some estimates, a mechanism that compensates countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) could funnel billions of dollars per year towards forest conservation. However the effectiveness of such a mechanism will hinge on the quality of data. Effective mapping and monitoring of forest carbon stores is absolutely key to any mechanism that compensates countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation.

Complete map of world forests to help REDD carbon trading initiative

(02/27/2008) Policymakers, conservationists and scientists have high hopes that REDD, a mechanism for compensating countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, will spur a massive flow of funds to tropical countries, helping preserve rainforests and delivering economic benefits to impoverished rural communities. To date, one of the biggest hurdles for the initiative has been establishing a baseline for deforestation rates — in order to compensate countries for “avoided deforestation” it first must be known how much forest the country has been losing on a historical basis. Until now, with some notable exceptions, this data was based largely on spotty satellite assessment and surveys of national forestry departments by the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization.

New satellite system will penetrate clouds to track deforestation

(12/05/2007) Satellite monitoring will play a critical role in any agreement that compensates tropical countries for preserving their forests, such as “Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation” (REDD) mechanisms currently under discussion at UN climate talks in Bali. Released Tuesday, a new study, “New Eyes in the Sky: Cloud-Free Tropical Forest Monitoring for REDD with the Japanese Advanced Land Observation Satellite (ALOS)”, details significant advancements in the field of remote sensing of forests.