Poised to wreak havoc on the climate of Earth, our only home, is a phenomenon we’ve been observing for 150 years: an increase in Earth’s mean temperature. To mitigate the global climatic disruption that humans put into motion long ago, the actors in the forest carbon offset market encourage landowners to sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide (the culprit in global temperature increases) in return for a payment for ecosystem service based on financial unit called a metric ton carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e). The regulatory and institutional frameworks of the forest carbon market are developing rapidly, yet one of the most urgent regulatory issues for a viable quality market is forest carbon financial accounting under International Accounting Standards (IAS) and U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

We predict forest carbon offset assets will become a thriving investment asset class with significant equitable distribution of revenues based in a transparent financial accounting mechanism. This article introduces forest carbon assets as an alternative asset class under IAS and U.S. GAAP.

Part 1: Financial Accounting

1.1 The Value of Accounting

In order for the forest carbon market to function adequately and develop fully, clear financial accounting standards for forest carbon offsets must be established. Entities possessing forest carbon offsets currently have no financial accounting guidance to follow, and as a result there is no transparency in the market due to the variety of accounting methods being used. Lack of uniform financial accounting makes it difficult to fairly compare financial statements between forest carbon offset projects, whether they are in the public or private sector. Until financial accounting rules are issued, difficulty regarding information transparency and comparability will persist in the forest carbon markets regardless of international policy direction.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) in May 2007 released a survey of 26 major European organizations affected by the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). The survey looked at the accounting approaches for ETS allowances and Certified Emission Reductions (CERs), both acquired and self-generated. CERs are the tons produced by projects that trade under the Kyoto Protocol. Even though the study relates to the EU compliance market, its findings may provide insight for the forest carbon market. The survey found on the balance sheet that

- 29% of participants accounted for self-generated CERs as inventory upon generation, at an allocated cost of production (see Inventory Accounting Methodology, below)

- 13% recorded the CERs as intangible fixed assets, at fair value (see Intangible

Accounting Methodology, below) - 29% did not recognize the CERs until they were used/sold

- 29% used other treatments

Whenever the asset is sold, money exchanges hands in return for forest carbon offset ownership rights. Accordingly, forest carbon offsets qualify as assets for financial accounting purposes because they are entity controlled and provide future economic benefits.

Despite the lack of clear rules, various accounting methods applicable to forest carbon offsets are present in existing standards under IAS and U.S. GAAP. In determining the appropriate accounting for forest carbon offsets, considering their character is imperative. The use of the forest carbon offsets determines their nature, which in turn dictates how they should be classified in the financial statements. This directly impacts the financial value perceived by the public and private sectors of forest carbon offsets.

1.2 Inventory Accounting Methodology

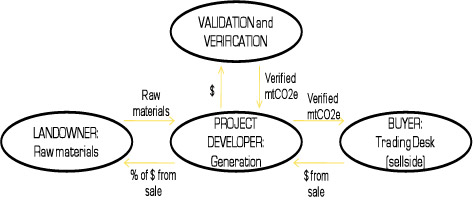

In the following example, a landowner hires a forest carbon offset project developer to generate forest carbon offsets on their property, regardless of the forest carbon asset class. The landowner uses an inventory accounting method. The forest carbon offset project developer sells the forest carbon offsets to a wholesaler. Using the generation analogy, a carbon forest offset project has three stages:

- Raw materials sourcing

- Generation

- Sales

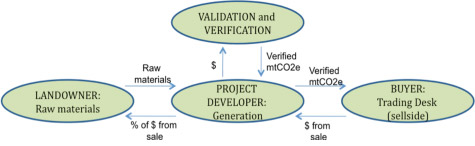

The transaction process flow is shown in Figure 1: Forest Carbon Offset Transaction Process Flow.

Figure 1: Forest Carbon Offset Transaction Process Flow

1.2.1 Inventory Accounting Methodology Example

A broker purchases 1,000 mtCO2e forest carbon offsets from a developer whose forest carbon offset project is based in the Central American rainforest. Purchase price is $5 per forest carbon offset and the unit cost for the developer is $2. The total amount the broker pays in the sale is $5,000. The broker records the $5,000 sale on its balance sheet as inventory. The journal entry for the broker’s purchase is as follows:

Credit Inventory $5,000

-

Debit Accounts payable $5,000

The gross amount the developer realizes from the sale is also $5,000 less any selling costs, but for this example we will assume the developer incurs no costs to sell the forest carbon offsets. The developer also realizes costs of goods sold (COGS) related to the forest carbon offsets of $2,000. The developer reduces inventory on its balance sheet and records the following journal entry for the sale:

Credit Accounts receivable 5,000

Debit Sales 5,000

Credit Cost of goods sold 2,000

Debit Inventory 2,000

When the broker pays the developer for the forest carbon offsets, it makes the following entry:

Credit Accounts payable 5,000

Debit Cash 5,000

The developer makes the following entry when it receives payment from the broker:

Credit Cash 5,000

Debit Accounts receivable 5,000

The broker now maintains this inventory on its balance sheet at lower of cost or market under U.S. GAAP or at lower of cost or net realizable value under IAS. If we follow the assumption there are no selling costs associated with the sale of forest carbon offsets, then the value of the inventory is the same regardless of whether U.S. GAAP or IAS is followed. When the broker subsequently sells the forest carbon offsets to a buyer, it removes the cost of inventory sold from the inventory account on its balance sheet and transfers it to cost of goods sold, an expense account on the income statement.

1.3 Intangible Accounting Methodology

Entities such as landowners, forest carbon offset project developers, and buyers may find it appropriate to account for forest carbon offsets as intangible assets. In the following example, a landowner hires a forest carbon offset project developer to generate forest carbon offsets on the landowner’s property, regardless of the forest asset class. The landowner uses an intangible assets accounting method. The forest carbon offset project developer sells the forest carbon offsets to a wholesaler. The transaction process flow is shown in Figure 1: Forest Carbon Offset Transaction Process Flow.

1.3.1 Intangible Accounting Methodology Example

A broker purchases 1,000 forest carbon offsets from a developer whose forest carbon offset project is based in the Central American rainforest. Purchase price is $5 per forest carbon offset; unit cost for the developer is $2. The total amount the broker pays in the sale is $5,000. Because the forest carbon offsets are separately acquired, the broker may record the $5,000 sale at cost on its balance sheet as intangible assets. The journal entry for the broker’s purchase is as follows:

Credit Intangibles 5,000

Debit Accounts payable 5,000

The gross amount the developer realizes from the sale is also $5,000 (less any selling costs, but for this example we will assume the developer incurs no costs to sell the forest carbon offsets). The developer does not realize any costs of goods sold related to the forest carbon offsets because the developer chooses to account for forest carbon offsets as intangible assets. Under U.S. GAAP, all costs are expensed as incurred. Therefore, the cost of the forest carbon offsets has already been expensed through the income statement, and the developer does not have any relevant balance sheet accounts to reduce. It records the following journal entry for the sale:

Credit Accounts receivable 5,000

Debit Sales 5,000

When the broker pays the developer for the forest carbon offsets, it makes the following entry:

Credit Accounts payable 5,000

Debit Cash 5,000

The developer makes the following entry when it receives payment from the broker:

Credit Cash 5,000

Debit Accounts receivable 5,000

Under U.S. GAAP, the broker maintains these intangibles on its balance sheet at fair value. Under IAS, the broker maintains the intangibles at cost less any accumulated impairment. The value of the intangibles will vary depending on whether U.S. GAAP or IAS is followed.

1.4 Cost Accounting for Forest Carbon Offsets

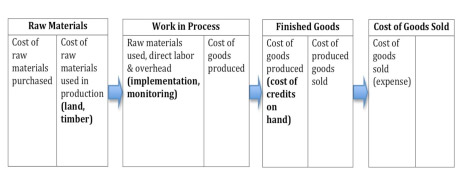

Cost accounting comprises various methods that can be used to calculate the per-unit cost for forest carbon offsets. In other words, this is how much it costs to produce each forest carbon offset asset. This unit cost is the basis for the monetary amount used in financial statements, regardless of the forest carbon offset classification as inventory or intangible assets, as discussed above. According to both IAS and U.S. GAAP, assets in the process of production constitute three types of inventory:

- Raw materials

- Work in process

- Finished goods

Production costs flow through the raw materials and work-in-process accounts before entering the finished goods account, where the aggregate cost of completed products is on the balance sheet. As goods are sold, their costs are removed from the finished goods account on the balance sheet and become an expense, cost of goods sold, on the income statement. Relevant production costs in forest carbon offset projects include the following:

- Land title acquisition, lease, and / or title insurance

- Forest carbon offset project design and technical data

- Implementation

- Monitoring, verification, and reporting

- Commercialization

Raw materials inventory includes the costs of materials, such as parts and equipment, from which a good is eventually manufactured. For a forest carbon offset project developer, these costs would relate to inputs such as land (owning and leasing) and timber from which the final outcome, a reduction in emissions, is produced. As raw materials are used in production, their costs transfer to the work in process account. All costs involved in the manufacturing process accumulate in this account. In addition to raw materials costs, the account also includes direct labor and overhead. Costs are transferred from work in process to the finished goods account as the manufacturing process concludes. For forest carbon offset project developers, a finished product is realized after validation and verification.

There may be a balance in all three accounts at the close of each accounting period. For raw materials and finished goods, this number represents the cost of items remaining at the periods’ close. For the work in process account, this number represents the accumulated costs incurred for goods still in the production process. The relative balances of these accounts depend on the nature of the manufacturer. For example, a manufacturer of products with lengthy, complex production processes (e.g., technological or electronic goods) may have a large balance in the work in process account relative to raw materials or finished goods. Conversely, a manufacturer of goods with short run production processes may have a relatively smaller work in process balance. For all three manufacturing accounts, inventory is held at lower of cost or net realizable value under IAS and at lower of cost or market under U.S. GAAP. In the context of forest carbon offset projects, the forest carbon offset project developer is likely the only entity to use this method because it is the only one engaged in a production process.

1.4.1 Cost Accounting Example

This example is hypothetical. All costs are purely speculative and are used only in the context of this example. We focus again on a forest carbon offset project based in the Central American rainforest. The forest carbon offset project is 10,000 hectares, and it spans 20 years. It is an Improved Forest Management forest carbon offset project according to the Voluntary Carbon Standard (VCS). Using the Gibbs-Brown average-biome approach, there exist 197 tons carbon stock per hectare climax forest. The developer estimates 2 tons carbon per hectare will be sequestered from the atmosphere each year, resulting in CO2 reductions of approximately 51,380 mtCO2e per year after a 30% VCS buffer. The mtCO2e from the VCS buffer are not returned to the forest carbon offset project developer. We estimate the amount of mtCO2e available-for-sale in the first year after verification at 5.138 mtCO2e per hectare. We assume the cost of raw materials is zero because the landowner already owns the land. The work in process account therefore only includes costs related to monitoring and overhead. Most overhead costs are fixed at the forest carbon offset project level. The process is shown in Figure 2: Cost Accounting Process.

Figure 2: Cost Accounting Process

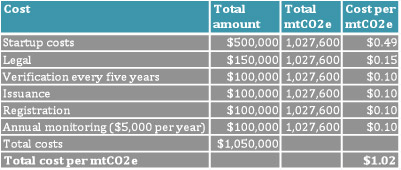

Without raw materials, costs begin in work in process. Costs relating to activities such as monitoring, verification, and registration accumulate in the work in process account as incurred. After forest carbon offsets are validated and verified, their associated cost moves to finished goods. When forest carbon offsets are sold to buyers, the cost of goods sold transfers from the finished goods account on the balance sheet to the cost of goods sold account on the income statement. To compute cost of goods sold, it is necessary to compute the per-unit manufacturing cost of the finished goods (see Figure 3: Per Unit Costs Incomplete). Once the unit cost is determined, this cost transfers with the units sold from Finished Goods to Cost of Goods Sold.

Figure 3: Per Unit Costs Incomplete

Because forest carbon offset projects have relatively high development and maintenance costs with minimal physical production and few raw materials, costs may vary over the years of a forest carbon offset project, even though the product, essentially abated carbon, remains largely homogenous. The unit cost of forest carbon offsets may also vary considerably between years. For example, assume verification, issuance, and registration occur every five years. If we allocate overhead based on annually determined rates, this would result in both over and under allocation of overhead costs throughout the lifetime of a forest carbon offset project.

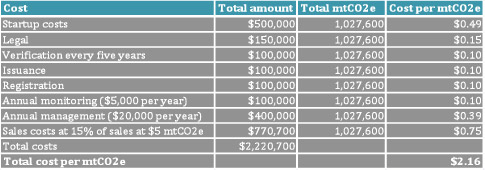

Viewing cost from a value chain perspective may help natural resource managers and communities make better-informed decisions before starting the production process. Including the lifetime costs of a product in its unit cost may help managers make the most effective pricing decisions. Even if the market essentially sets the price, however, there may still be benefits. Forest carbon offset projects can span decades, placing a great deal of importance on a forest carbon offset project’s design phase. Life cycle costing may enhance forest carbon offset project design through value engineering. With such processes, management has the opportunity to analyze the value chain, eliminating wasteful activities while boosting efficiency. The following chart (see Figure 4: Per Unit Costs Complete) shows the unit cost calculation using life cycle costing, with amount of cost shown on a per annum basis, spread over the number of units each affects.

Figure 4: Per Unit Costs Complete

Clearly, different methods of cost accounting impact a forest carbon offset project’s valuation, whether at $1.02 mtCO2e or $2.16 mtCO2e.

How developers calculate their unit cost, which depends on the cost accounting assumptions chosen, affects internal decision making. Fixed costs, of course, must be paid regardless of whether they are included in unit cost calculations. Therefore, if only variable costs are included in pricing decisions, sales proceeds may be insufficient to cover all the associated costs. Even if the market sets the price for forest carbon offsets, only including variable costs in unit cost calculations could still result in lower than expected profits. Furthermore, forecasts based on prices that do not include fixed costs may render future forest carbon offset projects unprofitable. This may cause developers to avoid taking on certain forest carbon offset projects that may be profitable but appear unattractive due to poorly informed decisions. The use of life cycle costing for internal decision making may remedy these problems.

- Not allowed for financial reporting purposes but may be a useful tool for management

- Focus on the value chain

- Costs incurred prior to production

- Production costs

- Costs incurred post-sale

- Helps internal decision making

- Idea of a product’s lifetime cost may help in pricing decisions

- Enhance product design through value engineering

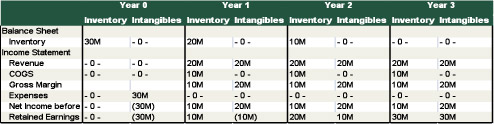

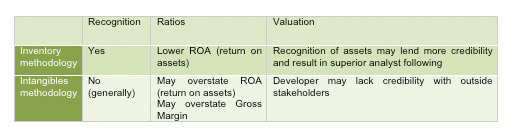

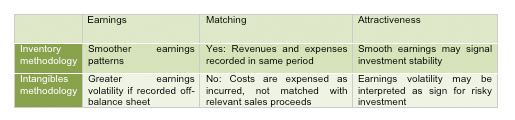

1.5 Comparison: Inventory Accounting Methodology vs. Intangibles Accounting Methodology

If forest carbon offsets are recorded on-balance sheet as inventory, variations in unit cost will be minimal, resulting from differences in cost accounting assumptions. Discrepancies in amounts recorded on-balance sheet for intangibles, however, may be more substantial. This holds for both IAS and U.S. GAAP because not all related costs are eligible for capitalization, and eligible costs vary between the two sets of standards. Regardless of what group of standards is followed, forest carbon offsets recorded as intangibles will most likely result in off-balance sheet classification. This is the logical result of the lack of an active market. Consequently, the major accounting implications from choosing one method over the other lie less in measurement and more in where the assets are recognized in the financial statements.

More simply put, accounting for forest carbon offsets as inventory results in balance sheet recognition, whereas accounting for them as intangibles results in a series of expenditures on the income statement with no balance sheet recognition. When forest carbon offsets are recorded on an entity’s balance sheet as inventory, they increase total assets, in turn diluting the entity’s return on assets. While the inventory methodology may therefore appear to be the less preferable treatment, suggesting the intangible methodology to be the favorable classification as off-balance sheet intangibles, academic research may prove otherwise, especially for entities whose assets are predominantly intangible. This mix of assets could be the case for landowners, forest carbon offset project owners, and forest carbon offset project developers in the forest carbon scenario. Findings indicate that when intangible assets are capitalized, an entity receives both superior analyst following and lower forecasting errors (Matolcsy, 2006). If intangibles are not capitalized, an entity shows few assets on the balance sheet along with negative operating cash flows. If an entity is concerned with analyst following and attractiveness to investors, it may consider accounting for forest carbon offsets as inventory.

Accounting for forest carbon offsets as inventory or intangibles also has implications for the income statement. The inventory option will result in smoother earnings patterns than will classification as intangibles. This is because of the matching principle. Inventory costs (the cost of goods sold) are expensed through the income statement when inventory is sold, and so both the revenue and expense from the sale of inventory are recorded in the same period. Alternatively, when forest carbon offsets are recorded as off-balance sheet intangibles, costs are expensed as incurred; these expenses are not matched with relevant sales proceeds. As a result, accounting for forest carbon offsets as intangibles will lead to greater earnings volatility. If an entity does not operate to a large extent with intangibles, the resulting earnings volatility may not have much of an effect on overall earnings. However, for an entity that operates mainly with intangibles, earnings volatility can have serious repercussions, such as the perception the entity is a risky investment.

1.5.1 Comparison: Inventory Accounting Methodology vs. Intangibles Accounting Methodology Example

For the following example, we assume only the following:

- Forest carbon offset project generates $30 million worth of forest carbon assets; all else equal and ignoring taxes

- Forest carbon offset project developer sells $20M annually of forest carbon assets, at a cost of $10M to develop, for 3 years

- Transactions impact balance sheet, income statement, and retained earnings

Figure 5: Inventory vs. Intangibles Accounting Methodology Impacts

From this example, we see that whether we choose inventory or intangibles accounting methodology impacts our valuation for

- Assets on the balance sheet (see Figure 6: Balance Sheet Impacts)

- Revenue and expenses on the income statement (see Figure 7: Income Statement Impacts)

Regardless of the accounting methodology one chooses, retained earnings at the end of the project remains the same. Both methods represent the same underlying economic transactions.

Figure 6: Balance Sheet Impacts

Figure 7: Income Statement Impacts

How we account for our forestry carbon offsets clearly has significant impacts that need to be addressed as soon as possible as we head towards both a UN post-Kyoto Protocol forestry carbon policy and a U.S. cap-and-trade forestry carbon policy.

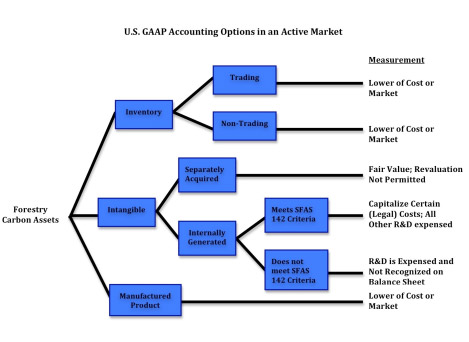

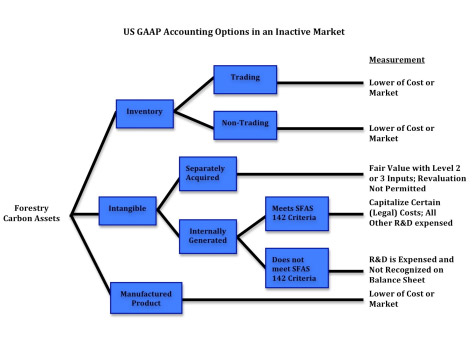

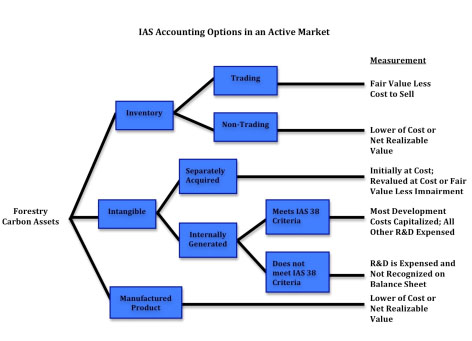

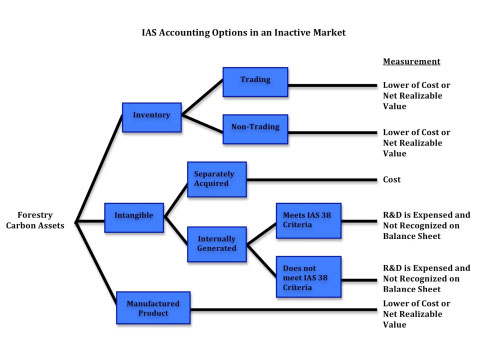

For further diagrammatic analysis, please see Figure 12: U.S. GAAP Accounting Options in an Active Market, Figure 13: U.S. GAAP Accounting Options in an Inactive Market, Figure 14: IAS Accounting Options in an Active Market, and Figure 15: IAS Accounting Options in an Inactive Market.

Part 2: Forest Carbon Offsets: Its Own Investment Asset Class?

2.1 Forestry Carbon Offsets Investment Class

The question we ask as market participants is whether forest carbon assets and offsets is becoming its own investment asset class. We have observed that the key lessons to developing a successful are effective communication, appropriate business strategy, understanding the offset generation process, focus on intergenerational equity, real property rights, and engaging finance and sustainability concurrently. If we can perform these tasks, forestry carbon offsets may become a thriving alternative investment asset class with significant equitable distribution of revenues based in a transparent financial accounting mechanism.

2.2 Effective Communication

Successful forest carbon offset projects have four components. These components form the “Rational Convergence” business strategy model (see Figure 8: Rational Convergence).

- Scientists will tell us that the “land dictates the rules” of the forest carbon offset project. This means that we must understand environmental science qualities of the land that encompasses our forest carbon offset project and its surrounding locale.

- Civil society and local communities and their proxies in civil society such as international nongovernmental organizations will tell us that local communities are the gatekeepers of a forest carbon offset project. This means we need to work within the local community to gain support for our forest carbon offset project because local communities are the catalysts for forest carbon offset project success.

- Governments organize rights, and they will tell us that we need to work within their existing legal frameworks to develop a forest carbon offset project. Yet these frameworks change over time, and there may exist different legal criteria at different levels of government, whether local, provincial, national, or international. Internationally accepted best practices may be preferred.

- Businesses structure risks, yet forest carbon offset projects succeed when they focus on mitigating risks as opposed to maximizing profits. This is due to the forest carbon offset market being dominated by the dictum of quality over quantity, because higher quality offsets receive a price premium (Thoumi, 2009).

Figure 8: Rational Convergence

2.3 Appropriate Business Strategy

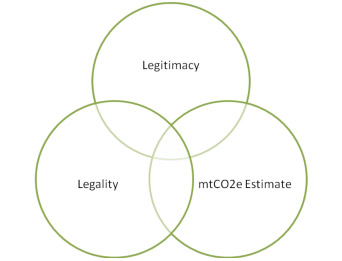

The successful strategic approach to forest carbon offset project development includes three stages. These stages are planning, screening, and implementation.

- Planning: Each forest carbon offset project is managed for aspects related to being real and measurable, permanent, transparent and credible, legal, marketable, and liquid, demonstrating co-benefits, having clear and prior consent of owners, minimizing business risk, minimizing sovereign risk, and providing assurance of completion.

- Screening: Each forest carbon offset project is screened for aspects related to legitimacy, legality, and forest carbon offset estimation (see Figure 9: Screening Tool).

Figure 9: Screening Tool

- Implementation: Each forest carbon project is developed with a complex systems approach to implementation, validation and verification, monitoring, adjustment, and sales. This approach is necessary for projects to realize successful outcomes.

2.4 Stages of Forest Carbon Offsets

Figure 10: Forest Carbon Offset Direct Sales Process

Buyers need transparency to price comparison shop. Sellers need liquidity to sell forest carbon offsets efficiently and effectively. Regulators need a market providing assurance of completion. Market participants generally use a direct sales model where forest carbon offsets are sold directly to an emitter (see Figure 10: Forest Carbon Offset Direct Sales Process). Generation has three stages: raw materials sourcing, validation/ verification and project development, and sales.

- Raw Materials Sourcing: A project owner needs to have clean and clear title to the land with appropriate socioeconomic engagement and biodiversity maintenance and enhancement possibilities.

- Validation and Verification: Project developers assemble all the parts needed for forest carbon offsets. The forest carbon project developer delivers the technical documents to a third-party certification mechanism for third-party independent verification.

- Sales: Buyers have five reasons to purchase forest carbon offsets. They purchase forest carbon offsets for compliance to regulated markets, precompliance to regulated markets, investing for a financial return, carbon neutral product offsetting, and public relations.

2.5 Intergenerational Equity

We can split businesses into two groups – those that create value and those that appropriate or take value (Afuah, 2009). Because forest carbon offset projects should directly improve carbon sequestration and indirectly improve or maintain other eco-system services, it is possible to discuss forest carbon offset assets as value creation projects for which the sum of the whole at the end of the process is greater than the sum of the whole at the beginning. Forest carbon offset projects usually span 20 to 100 years. Consequently, we can discuss forest carbon offset projects in the context of inter-generational equity.

2.6 Real Property Rights

Forest land is real property, and a forest carbon offset project needs to be understood within this context. Legal rights that transfer to the buyer are related to real property ownership, with rights of possession including boundary establishment, the rights to control how the land is used, the rights to benefits arising from the land, and the rights to give, sell, encumber, or bequeath rights or a portion of rights to others (McEvoy, 1998). A forest carbon offset project must develop the legal capacity to give, sell, encumber or bequeath rights or a portion of rights to others in a commercially viable manner while protecting the public interest of the location where the rights originate.

2.7 Finance and Sustainability Engagement

Financial institutions play a key role in sustainable economic development. How finance currently operates in society may not be congruent with the principles of this sustainability framework. Below we outline three issues that may need to be addressed by the finance industry if it chooses to improve is sustainability capacity.

- Discounting

- Pro Discounting finds the present value of cash flows today by using the time value of money equation.

- Con Discounting without a rational time horizon.

- Accounting

- Pro Accounting allows us to transact private sector and public sector globally.

- Con How we report on natural resources also has discrepancies. For example, methods to account for nonsustainable extractive services, such as for coal, do not apply a limit to the amount that can be extracted from a mine given the growth rate of the resource.

- Growth Potential

- Pro This discussion may be academic.

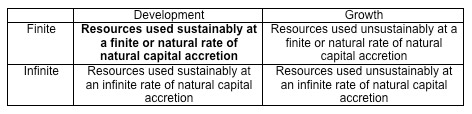

- Con Analysis of growth potential in finance does not make a coherent separation between growth and development and the finite and the infinite (see

Figure 11: Development, Growth, and Natural Capital Accretion) because growth and development are not inherently the same process. One can have development without growth, and one can have growth without development. Development implies overall progress for the community in a sustainable fashion. Because the Earth has limited resources, our economic systems should use resources more efficiently with the goal of creating intergenerational equity. In summary, any financial analysis could be compared to a baseline where resources are used sustainably at a finite or natural rate of natural capital accretion.

Development Growth

Finite Resources used sustainably at a finite or natural rate of natural capital accretion Resources used unsustainably at a finite or natural rate of natural capital accretion

Infinite Resources used sustainably at an infinite rate of natural capital accretion Resources used unsustainably at an infinite rate of natural capital accretion

Figure 11: Development, Growth, and Natural Capital Accretion

Summary

Financial accounting for forest carbon offsets is important for both internal and external decision making for forest carbon offset projects. Appropriate cost accounting is significant for landowners and forest carbon offset project developers who make crucial decisions based on cost calculations. Appropriate and uniform classification of forest carbon offsets in the financial statements is imperative both for internal decision making and for external stakeholders such as communities, not-for-profits, nongovernmental organizations, regulators, public sector investors, and private sector investors. Without clear financial accounting guidance for forest carbon and voluntary offsets, financial comparability across forest carbon offset projects will remain vague, thus making it impossible to gauge the financial health of a forest carbon offset project or to determine whether there exists equitable distribution of revenue to local communities.

Furthermore, how we account for our forestry carbon offsets clearly has significant impacts that need to be addressed as soon as possible as we head towards both a UN post-Kyoto Protocol forestry carbon policy and a U.S. cap-and-trade forestry carbon policy. We need to be able to financially account for our forestry carbon offsets with permanence, regularity, consistency, prudence, and full disclosure and materiality for our forestry carbon offset market to grow as an industry into an alternative investment asset class.

To propel the forestry carbon offset market industry into an alternative investment asset class, we recommend the following actions be taken:

- Create appropriate uniform financial accounting processes for forestry carbon offsets as an imperative for both internal decision making and external stake-holders.

- Issue financial accounting guidance so the forestry carbon market matures into a viable and active market based in liquidity, transparency, and assurance of completion.

Figure 12: U.S. GAAP Accounting Options in an Active Market

Figure 13: U.S. GAAP Accounting Options in an Inactive Market

Figure 14: IAS Accounting Options in an Active Market

Figure 15: IAS Accounting Options in an Inactive Market

Talitha Haller is a short-term associate with the Social Carbon Company in Brazil. She graduated from the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan with a Master of Accounting and a BBA. She can be reached at talitha.haller (at) gmail.com.

Gabriel Thoumi is a forest carbon project developer and consultant with Forest Carbon Offsets, LLC, a global forest carbon offset project development firm. He is a graduate with an MBA from Ross School of Business, an MSc from the School of Natural Resources and Environment, and a Graduate Certificate in Real Estate Development from the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning all from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at gabrielthoumi (at) forestcarbonoffsets.net.

In this article, 1 forest carbon offset = 1 mtCO2e. A supporting technical paper is available at http://www.forestcarbonportal.com/article.php?item=1118.

References

- Afuah, A. (2009). Strategic Innovation. Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Ardern, D., & Keys, R. (2008). IASB Agenda Proposal on Intangible Assets. International Accounting Standards Board

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2001, June). Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 142: Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets: http://www.fasb.org/pdf/fas142.pdf

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2008, June). Proposed FSP on ARB 43 (ARB 43-a): www.fasb.org/fasb_staff_positions/prop_fsp_arb43-a.pdf

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2008). Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 151: Inventory Costs: http://www.fasb.org/pdf/aop_FAS151.pdf

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (April 8, 2009). Accounting for Emission Trading Schemes: Initial Accounting for Offsets Received Free of Charge in a Cap and Trade Program. Board Meeting Handout, Financial Accounting Standards Board.

- International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) Foundation. (2009, January 1). International Accounting Standard 2: Inventories.

- International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) Foundation. (2009, January 31). International Accounting Standard 38: Intangible Assets

- International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) & PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2007, May). Uncertainty in Accounting for the EU Emissions Trading Scheme and Certified Emission Reductions. PricewaterhouseCoopers.

- Gullison, et al. (2007, May 10). Tropical Forests and Climate Policy. Science Vol. 316. no. 5827, pp. 985 – 986.

- Matolcsy, Z. A. (2006). Capitalized Intangibles and Financial Analysis. Accounting and Finance , 46(3), 457-479.

- McEvoy, T. J. (1998). Legal Aspects of Owning and Managing Woodlands. Chicago, IL: Island Press.

- Thoumi, G. (2009). Emeralds on the Equator: An Avoided Deforestation Carbon Markets Strategies Manual. Sandy, UT: Aardvark Global Publishing.

- World Bank. (2009, August 4). World Bank Signs First ERPA for Reforestation Project in DRC.