Satellites have long been used to detect and monitor environmental change, but capabilities have vastly improved since the early 1970s when Landsat images were first revealed to the public. Today Google Earth has democratized the availability of satellite imagery, putting high resolution images of the planet within reach of anyone with access to the Internet. In the process, Google Earth has emerged as potent tool for conservation, allowing scientists, activists, and even the general public to create compelling presentations that reach and engage the masses.

Tryse on the jungle path in Bako National Park in Sarawak

“A decade ago, high-resolution satellite imagery for the whole planet would have been accessible only to a handful of people working in government agencies, resource extraction, or as scientists. Today it is in the hands of hundreds of millions of people,” said Tryse. “It’s impossible to care about something if you don’t know it exists, but now people can fly across the planet and zoom in to see for themselves in a whole different way many of the issues of today, whether it’s a humanitarian crisis like burned down villages in Darfur or an environmental issue like what little forest remains for some of the world’s most endangered animals on the EDGE list.”

Mongabay: What is your background and when did you start developing conservation applications for Google Earth?

Tryse with his wife Edel in the Colca canyon, Peru.

|

David Tryse: My background is in IT but I’ve always been interested in nature and environmental issues. This interest was particularly brought to

life during a year-long round-the-world trip I did in 2005 together

with my wife, especially a month we spent in Borneo – seeing sawmill

after sawmill on the river-sides when traveling by boat in Sarawak and

seeing nothing but endless palm-oil plantations both sides of the the

road for a full day when crossing the whole state of Sabah. It would

all have been forest when I was born (I’m just 30).

When back working again I started looking for ways I might be able to

do something useful for conservation with my skills et. I got in touch

with edgeofexistence.org — an interesting new conservation effort which selects focus species based on genetic distinctiveness [I think I heard of them through mongabay

actually ;-)] — to see if they would be interested in a Google Earth layer to visualize their

list of endangered mammals and their distribution. The company where I

work happened to be celebrating 25 years at the time with a drive to

donate money to charity when employees donate volunteer hours, so I

managed to raise the EDGE programme a bit of money through this

project as well.

EDGE of Existence: Amphibians. This KML shows 100 of the worlds most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) amphibian species. It was created for the Zoological Society of London’s EDGE of Existence program. Google Earth file. |

The Google Earth Outreach team were fantastically enthusiastic and

helpful after I got in touch with them afterwards. I helped

beta-test one of their KML-tools and the EDGE KML is featured as a

case study on their site now to help inspire other charities.

I’ve made a number of other Google Earth layers since then as personal

projects, about oil spills, deforestation and other issues. One

comparing deforestation statistics for different countries in

particular made its way around the internet to many environmental

blogs and Google Earth tech blogs. I think a number of them picked it up from Mongabay, so thanks again Rhett :-).

Mongabay: Has tracking deforestation via Google Earth offered any surprises?

David Tryse: People sometimes say poetically that you can’t see the

borders between different countries from space… but that is actually

not true any more. There are a number of places where the aggressive

deforestation in one country right up to the border of another makes

it possible to make out clearly in Google Earth, even when zoomed out

very far. Mexico-Guatemala, Brazil-Bolivia, Malaysia-Brunei, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and

Thailand vs Cambodia and Laos are a few.

Mongabay: What makes Google Earth a powerful tool for conservation?

|

|

David Tryse: A decade ago, high-resolution satellite imagery for the whole planet would have been accessible only to a handful of people working in government agencies, resource extraction, or as scientists. Today it is in the hands of hundreds of millions of people. It’s impossible to care about something if you don’t know it

exists, but now people can fly across the planet and zoom in to “see

for themself” in a whole different way many of the issues of today,

weather it’d be a humanitarian crisis like burned down villages in

Darfur or an environmental issue like how very little forest is left

for some of the worlds most endangered animals on the EDGE list. In

seconds anyone can zoom in to for example see the huge fires from

Shell’s gas-flaring operations in the Nigerian delta or follow the

discolored toxic runoff along a hundred kilometers of (recently

pristine) rainforest river downstream of a gold mine in Peru or

Indonesian Papua. I am convinced that this ease of access to

information that Google Earth is a great example of must be able to

change how citizens choose their governments and how consumers choose

their products in the future.

Mongabay: What projects are you working on now?

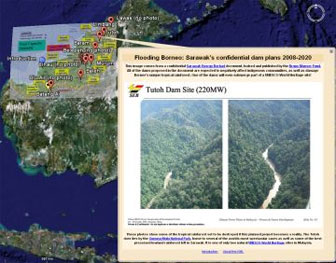

David Tryse: At the moment I’m working on an online application that will help

others create Google Earth projects similar to some of the ones I have

made in the past. The tool will let you create visualizations similar

to the “Disappearing Forests” KML with any data by just uploading a

spreadsheet with country level statistics. I hope to launch it at

www.kmlfactbook.org shortly.

Mongabay: Could you elaborate on kmlfactbook?

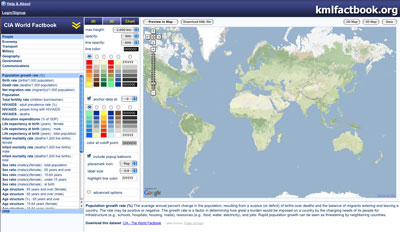

kmlfactbook. |

David Tryse: The idea behind kmlfactbook is to allow anyone to create impressive

visualizations of global data-sets in Google Earth, without the need

to know any programming or have experience with databases. All that

is needed is to upload a simple spreadsheet in CSV format.

Currently kmlfactbook can create 3D prism (or 3D country border

outline) maps, which have started to become a popular way to show data

in Google Earth, as well as more traditional 2D choropleth maps and

pie charts. You can customize colors, icons and a handful of other

options for the output. The visualization can then either be

downloaded as a KML file to view in the Google Earth application, or

be viewed directly online inside kmlfactbook.org using Google Maps or

the new Google Earth browser plugin.

In addition to uploading custom data to create visualizations from the

site is pre-loaded with data from the CIA World Factbook plus the

great collection of environmental data published for free by the nice

people at World Resources Institute EarthTrends. This allows you to

quickly put together a file comparing for example CO2 emissions or

deforestation rates between different countries, in a way that I hope

might be more visually interesting than using a simple table or graph.

Tryse in Pahuma Orchid Reserve, a cloud forest a couple hours from Quito in Ecuador. Tryse with a baby giant anteater in Pilpintuwasi, a little animal orphanage close to Iquitos. |

At the moment kmlfactbook.org can only work with country level data,

but I aim to add US states and other regional sub-divisions in the

future (as well as more options to customize the visualizations).

My hope is that kmlfactbook will be useful for NGOs and other people

who want to use Google Earth as an interesting new way to highlight

their data. I received a lot of interest about the Disappearing

Forests KML I made last year, and now the site can help anyone make

similar visualizations without needing to spend days in PHP and MySQL.

David Tryse’s Google Earth Applications

RELATED

Satellites and Google Earth Prove Potent Conservation Tool

(03/26/2009) Armed with vivid images from space and remote sensing data, scientists, environmentalists, and armchair conservationists are now tracking threats to the planet and making the information available to anyone with an Internet connection.