Inflatable concentrators may cut cost of solar below conventional power plants

Inflatable concentrators may cut cost of solar

below conventional power plants

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

July 8, 2007

Cool Earth Solar, a Livermore, California-based company developing an innovative way for capturing solar energy, has merged with Radiant Energy, a developer and owner of renewable and clean energy power plants including solar, geothermal, and hydroelectric.

Rob Lamkin, CEO of Radiant Energy, says the merger will help ramp up the technology, which uses inflatable solar concentrators to minimize use of refined silicon, a costly ingredient in solar cells.

“The management at Radiant Energy have over 20 years of experience in power plant development and project finance,” Lamkin told mongabay.com via email. “Since Cool Earth Solar is initially focused on utility scale plants, this experience and expertise gained in the merger will accelerate the number and size of power plants being built utilizing this break through technology. The successful development of our first large solar power plant is critical to our continued growth and success. ”

The Cool Earth System “started as a comprehensive scientific search for a low-risk approach to reach global carbon neutrality by 2050,” according to the firm. Cool Earth’s analysis “revealed only one technology that is inexpensive enough for such radical free-market-based growth and requires no miracles in materials or production capacity: a tensegrity-based concentrated photovoltaic system. Tensegrity is a trick of mechanics that allows us to minimize use of man-made materials such as solar cells, plastic, and steel, while maximizing use of natural materials like air, water, and soil. |

Cool Earth Solar, which recently raised nearly $1 million in seed capital, is planning to start construction on its first utility scale power plant by the end of this year, but Lamkin says the company is “currently in negations and discussions with several utilities to sell long-term clean renewable solar energy from our power plants.” He adds that Cool Earth Solar continues to seek additional sites for its plants.

While the firm plans to initially focus on power plant installations, the technology could eventually be used for distributed applications, for example turning farms into small-scale localized power generators.

Lamkin says the technology could dramatically reduce the cost solar energy, bringing it below the cost natural gas-fired power plants.

“We believe our technology is already near the long term price of conventional power plants burning natural gas,” Lamkin said. “Our goal is that we will also someday be competitive with coal power plants.”

The technology, as described in a February 2007 mongabay.com article:

Balloon technology could cut cost of solar energy 90% by 2010

With high energy prices and mounting concerns over human-induced climate change, there is intense interest in renewable energy, especially solar, which produces no pollution and is readily available in the form of sunlight.

In recent years, however, the solar-energy market has been hampered by supply shortages of refined silicon, the critical resource needed for solar-cell fabrication. Further, because solar installations traditionally require a large surface area to capture as much sunlight as possible, solar arrays often take up real estate, occupying land used agricultural production and other purposes. Without government subsidies, solar is not presently viable in many areas.

Given the promise of solar, a slew of companies are working to address these concerns. Some are attempting to tackle the real-estate issue by adding solar to office buildings—where routine maintenance is sometimes a hassle—or constructing multi-use structures like carports that can serve as solar arrays. Google and Kyocera are two firms that have implemented such systems, but these are not practical in rural areas, where solar would sometimes be most useful. Further, these designs require sizeable amounts of silicon, where high prices remain a limiting factor.

|

Now an innovative startup is developing a solar design that may put these issues to rest by reducing the need for costly polysilicon and real estate.

Cool Earth Solar, based in Livermore, California, believes its technology could make solar farming economically competitive within three years by making solar cheaper than coal and allowing farmers to become net suppliers of electricity.

“In short we are developing free-market-hyper-competitive renewable energy with the mission of reaching global carbon neutrality,” Cool Earth Solar founder Dr. Eric B. Cummings told mongabay.com via email. “We are working to reduce the cost of solar electricity by a factor of 25, making it cheaper to produce than energy from coal or other non-renewable sources. By developing a solution from minimal, low-cost materials, we aim to make solar generation as profitable as today’s best investment options.”

Cummings’s lofty objectives are supported by an impressive background. Earning an M.S. degree from Caltech in aeronautics and his B.S. degree from Penn State University in engineering science, Cummings returned to Caltech for his Ph.D in aeronautics and chemistry. There he also won Caltech’s top honor, the Francis Clauser Prize, awarded “for opening new avenues of human thought and endeavor,” as well as Caltech’s William H. Ballhaus Prize for his thesis work on lasers. After spending eight years at Sandia National Laboratories in Livermore, Cummings founded Cool Earth Solar.

About 89 petawatts of sunlight reach the Earth’s surface annually. Humans use about 15 terawatts of average power per year. There is plenty of room for expansion. |

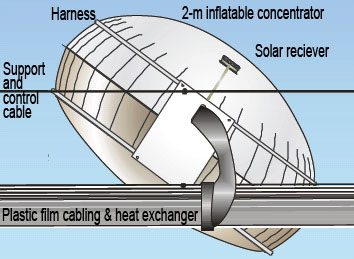

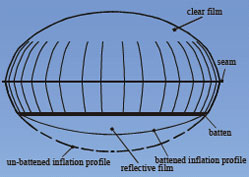

The closely-held firm has developed a technology that uses a string of balloons to concentrate and capture the sun’s energy without occupying valuable real estate or using large amounts of silicon.

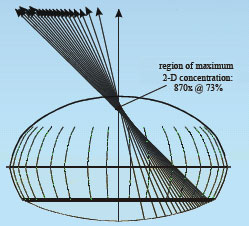

“Inflatable concentrators gather light and focus it onto photovoltaic cells, increasing the energy impacting the cells many times over,” the Cool Earth website explains. “Series of concentrators are suspended on support and control cables stretched between poles. By suspending the concentrators, vast areas of land can be easily converted for solar-energy production with limited environmental impact. The ground beneath the concentrators remains free for other uses, such as farming or ranching.”

The firm notes that its design “costs 400 times less per collected area than conventional mirrors, can withstand 100 m.p.h. winds, and can protect the mirror surface and receiver from rain, insects, and dirt,” issues that can significantly reduce the productivity of solar cells.

Cummings says each balloon, measuring two meters (6 1/2 feet) in diameter, can generate 500 watts of electricity and will eventually cost less than $2. With low maintenance and replacement costs, he believes the system will significantly reduce the cost of solar energy from the current price of around $4 per watt of installed capacity to levels where is competes directly with fossil fuel-based energy sources. The technology will offer new economic opportunities for farmers who will be able to “farm” electricity in addition to their crops.

Cool Earth Solar says its inflatable mirrors are 400 times cheaper than polished aluminum mirrors, cost $2, can be repaired with tape, and are replaceable in 15 minutes. |

“Solar farms generate energy inexpensively—and generate profit for their operators,” the Cool Earth web site notes. “We are confident that our minimum-material design and use of commodity materials will cut the cost of photovoltaic electricity in a 1 megawatt installation to 29 cents per watt by 2010. At that price, solar farming is a highly attractive option for land-holders. We can then expect free-market forces to drive the spread of clean solar-energy generation.”

“The big advantage of our system in rural areas is the abundance of area that is easy to access and maintain (far easier than up on a rooftop), the ease of setting up large power plants (at roughly eight acres per megawatt of electricity), and less resistance from homeowner associations,” Cummings explained via e-mail.

Gopal Shanker, president of Récolte Energy, a green-energy consultancy firm in Napa, California, says the system seems to offer a lot of potential for the wine industry.

“While I haven’t seen the technology, it sounds like it could work well for the wine industry, since it’s off-the-ground and wouldn’t shade grapes,” he said in a conversation with mongabay.com. “The ease of maintenance and low replacement costs would be a big benefit.”

Shanker, who is working on a proposal to make Napa County a net exporter of clean energy within five years, says that if Cool Earth delivers on its goal of 29-cent-per-watt solar power it would be a revolution in the energy industry.

“We’re looking for anything that makes solar cost competitive on a massive scale. Right now the total install cost for solar is running $7-$10 per watt,” he said, “so 29 cents per watt would eliminate the need for subsidies under the California Solar Initiative and transform solar energy from a green decision to an economic one. We’d be very interested in taking a closer look at the system”

Shanker may have that chance later this year. Cummings says that Cool Earth plans to have pilot installations by the fourth quarter of 2007.

“We aim to do what no company or government has yet achieved, and we aim to do it within the next few years,” the Cool Earth Solar web site says. “Our goals are ambitious. Our solution is innovative. Our technology is ready.”