A look at the biodiversity extinction crisis

A look at the biodiversity extinction crisis

Education is the key says tropical biologist David L. Pearson

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

October 6, 2006

An interview with Dr. David L. Pearson

As tropical forests — the world’s biological treasure troves — continue to dwindle, biologists are racing to devise ways to save them and their resident biodiversity. While many conservation biologists talk about population viability analysis and intricacies of reserve layouts, David L. Pearson, a research professor at the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University (ASU) in Tempe, Arizona, focuses on a different approach: education.

Pearson after a long day of field work in New Caledonia in July 2006

|

Pearson, whose work includes hundreds of books and papers including a series of beautifully illustrated wildlife guides for regions in Latin America, believes that lack of knowledge about ecosystems is one of the most significant hurdles to addressing the present biodiversity crisis. Fluent in five languages and able to “get along” in several more, Pearson conducts week-long workshops around the world to explain the basics of biodiversity and introduce “critical thinking” to audiences that include local government officials, business people, educators, students, and environmentalists. Pearson’s trips are largely self-financed, though he says seeing the enthusiasm of workshop participants in developing countries is reward in and of itself. Pearson is also a contributor to Ask A Biologist, an educational resource for students K-12, and their teachers and parents

In October 2006, I had the privilege of meeting with Dr. Pearson at his ASU office where he answered some questions on his work in education and conservation biology, his travels and passions, and the future of biodiversity.

Rhett A Butler (Mongabay):

You have done a lot of research on tiger beetles. What can these insects teach us about the broader ecosystem? Can they serve as a proxy or bioindicator of the health of an ecosystem? Have you observed any relationship between habitat degradation or loss and beetle biodiversity?

David L. Pearson (DLP):

There are an overwhelming number of species in the world. The majority of them (especially insects, nematodes, bacteria, and fungi) probably have not even been seen or described by scientists yet. How can we plan for conservation efforts or sensible long term management for them and their habitats if we don’t even know they are there? Even more important than their names, we don’t know what their habits and needs are for survival.

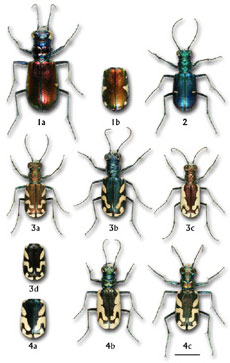

A plate of tiger beetles from “A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada” (Oxford Univ. Press, 2006)

|

One controversial alternative is to use some of the few groups of plants and animals, such as tiger beetles, butterflies and birds, that have been studied more thoroughly to represent all these other unknown species. We call these representative species “surrogates” or “bioindicators.” Because good indicators are very sensitive to changes in the environment, we can detect the impact of change in these indicators long before we would see it otherwise. In the old days, coal miners would carry canaries in cages down into the mine shafts with them. The canaries were much more sensitive to poison gases than humans, so the miners would watch the cages regularly, and if a canary all of a sudden started getting sick, the miners would run for the nearest entrance to avoid the gas they themselves could not yet smell.

In addition, indicator species can be studied across large areas, and where we find more of the indicator, we often can find more of many other types of species that are much harder to see and find. Using this method we can quickly find areas rich in species and give them a high priority for study and conservation efforts.

We have been successful in applying some of these indicators to conservation problems, but we have to be careful because one small group of species, such as tiger beetles, may not always represent all of the other species in the habitat. We have found that indicator studies are much more likely to be useful if we use several indicators simultaneously, for instance, one predator, one leaf eater, and one plant, to better represent the entire habitat. We were able, for example, to use tiger beetles along with birds, butterflies and ants to help establish the boundaries of a new national park in n.e. Madagascar. By showing where the greatest number of species occurred of all these different types of indicators, the government drew the boundaries to make sure that the greatest number of species of many other organisms like frogs and orchids would also be protected.

Mongabay: What is your outlook for global biodiversity in the future? Do you believe we are facing the “Sixth Extinction” crisis as many biologists have warned?

DLP:

I have to maintain some level of optimism, or I wouldn’t be able to continue in conservation. Back in the 1960s’ some ecologists predicted that by the year 2000 there would be no more tropical rain forest left in the world. Fortunately they were wrong. We need to balance awareness of the dangers to the environment and biodiversity with a positive attitude that we can do something to stop or at least slow down the impacts that are destroying this and other environments. If we develop a doomsday mentality, we run the risk of deciding that there is nothing we can do about it, and we stop trying. I always end my talks on tropical rain forest with examples of successes in habitat preservation, environmental education and changes in government and business attitudes.

Mongabay: Why is biodiversity important? Does it matter that some birds and insects are at risk of going extinct within a generation?

DLP:

Biodiversity’s importance includes the availability and right of everyone to enjoy Nature, a psychological factor if anything. But biodiversity also impacts our quality of life in other more measurable ways. For instance, a lot of our food (chicken, coconut, vanilla, chocolate, coffee, tea), consumer products (rubber, aluminum) and many medicines come from tropical forests. We have investigated less than 10% of the plants and animals in these rain forest to look for their potential as additional foods, medicines and other useful economic products. Knowledge of the interactions of insects and birds with economically important plants through pollination, plague and disease control are vital for our ability to mange these and other habitats for long term use. A single bee or bat extinction could mean that an economically important tree will not survive because it is dependent on that species for pollination.

Mongabay: Has conservation been successful? Have you noticed changes in how conservation is implemented in recent years. How can conservation efforts be improved to preserve biodiversity and ecosystem services?

DLP:

With more than 6 billion people in the world, we have to measure our successes in conservation with a balanced view. Will we ever again have all the pristine environments of the 1800s? No, and if that were the goal of conservation, we would have little chance for success. Instead, we need to put our goals in perspective. Yes, we can work to conserve as large patches of pristine habitat as we can, but we know that as remnants, they will likely have to be heavily managed. On the other hand, much of the world’s future biodiversity will be preserved in secondary habitats of cut over forests, city lots, and patches. These are habitats that few want to study or preserve. Yet if we don’t start making plans for these scrub habitats now, even they may be gone before we realize how important they are.

Mongabay: You’ve done a lot of work in environmental education through workshops. Do you believe such programs are a key component to conservation efforts? Does it help ferment interest and awareness in wildlife and wildlands?

DLP:

My workshops around the world focus on the “Basics of Biodiversity.” In some ways the species and habitats we discuss in these workshops are a pretext for developing a way of thinking we call “critical thinking.” People with the best intentions can work at conservation, but too often many of them base their arguments and protests on what they think the answer should be or wish it was. With little or no actual solid information to back up arguments in support of conservation or long term management practices, we lose out in the long run in our conservation efforts. A recent example of where critical thinking could have been better applied was in the recent claims of rediscovering the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in a swamp in Arkansas. As much as all of us wanted to believe it was true, such a fantastic claim needed fantastic evidence. That evidence, in the end was not sufficient. The backlash that may come, will be in disbelief of future discoveries that are indeed valid. We have supplied doubt and lack of credibility that may set back conservation and land preservation efforts considerably because we didn’t think or look at this claim critically enough. I always tell the participants in my workshops, watch out for two red flags in discussions of conservation efforts and avoid using them yourself, “Everyone knows” and “They all say.” These are arguments given by losers.

Mongabay: Most of your efforts in recent years focus on local engagement, but is it also important to educate Americans and other Westerners about issues and places halfway around the world?

DLP:

Absolutely, North Americans need to be educated about these issues even if they never visit far flung areas themselves. It should be obvious to everyone that the US, with 7% of the world’s population (we are now the third most populous country in the world) uses perhaps 20% or more of the world’s energy. That energy comes from all over the world, and we can not afford to perceive ourselves as isolated. Our global economy is only a reflection of how connected the world is, even to small countries that many of our citizens have never heard of.

Even something as mundane as shopping in a grocery store puts you in a position of economic power and environmental impact. For instance, what you chose to consume and pay for influences how much rain forest is cut down. Pineapple, sugar, aluminum, black pepper, tea, and sun-grown coffee are all products that can only be grown when the native rain forest is completely cut down. Products such as chocolate, vanilla, many medicines, and shade-grown coffee are products that can be harvested in intact or near intact rain forest. These are only a few connections among many more that show how much North Americans need to know of their power and ability to influence long term survival of biodiversity as well as the local people who are living among that biodiversity.

Mongabay: Do you believe sustainable development is a key component in conservation efforts? Is it better to focus on strict preserves or embrace multiple use initiatives?

DLP:

To put all your conservation efforts into fencing off tracts of pristine habitat is arrogant and ignorant. Of course there is a time and place for this type of preservation, but North Americans have to understand that peoples and cultures in other parts of the world have a right to survive and enjoy economic benefits. Treating other cultures as equals is not always a North American character, but it is in our own best interest to do so. The ideal conservation effort involves pursuing win-win situations, especially economically, that advance long term and rational use of natural resources. This goal can only be met with true partnerships, cooperation and deep understanding and sensitivity to other cultures. Forcing local people off their land so western ecotourists can see tigers may have many ramifications that in the long run will be detrimental to the very habitat and species you are trying to preserve.

Mongabay: What advice can you give students wanting to pursue a career in conservation or conservation biology? Are there specific degrees they should consider or is conservation so multi-faceted today that one could approach from a number of different disciplines?

DLP:

There are both undergraduate and graduate degrees in conservation biology, but probably more than these we need lawyers, business people, engineers, politicians, and decision makers trained well in their discipline but with an understanding and appreciation of the necessity of managing the natural world rationally. Biologists may help supply a lot of basic data and information, but few biologist are likely going to make the final decisions and economic determinations that will impact biodiversity and habitats.

Mongabay: You have traveled all of the world — to more than 60 countries, do you have a favorite place to visit?

DLP:

If the number of times I have visited a country reflects my favorite places, I have been to Peru more than 65 times since 1968 and Ecuador more than 50 times. I have been to Bhutan, India and Thailand fewer times, but many aspects of nature and the people there put them in my favorite category as well. Gabon, Uganda, and South Africa have taught me a lot, and they rank among my favorites, too.

Mongabay: What can people do here in the United States to help preserve biodiversity both locally and globally?

DLP:

Become aware of what your economic and political power is. Don’t be naive, but be optimistic. Study the facts, read books, attend workshops, listen and think critically. Vote for the people who will make rational and effective decisions, and if they aren’t available, consider jumping into the decision-making process yourself. Travel, learn about and appreciate other cultures. Avoid arrogance and ignorance.

A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada

Buy this book today and receive a 20% discount Oxford University Press

.