North Atlantic Ocean freshening could weaken Gulf Stream

North Atlantic Ocean freshening could weaken Gulf Stream

New study looks at combined causes of North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean freshening

Marine Biological Laboratory

August 24, 2006

A new analysis of 50 years of changes in freshwater inputs to the Arctic Ocean and North Atlantic may help shed light on what’s behind the recently observed freshening of the North Atlantic Ocean. In a report, published in the August 25, 2006 issue of the journal, Science, MBL (Marine Biological Laboratory) senior scientist Bruce J. Peterson and his colleagues describe a first-of-its-kind effort to create a big-picture view of hydrologic trends in the Arctic. Their analysis reveals that freshwater increases from Arctic Ocean sources appear to be highly linked to a fresher North Atlantic.

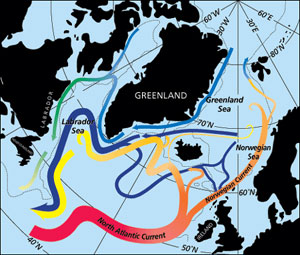

The North Atlantic Current Pathways associated with the transformation of warm subtropical waters into colder subpolar and polar waters in the northern North Atlantic. Along the subpolar gyre pathway the red to yellow transition indicates the cooling to Labrador Sea Water, which flows back to the subtropical gyre in the west as an intermediate depth current (yellow). More information RELATED ARTICLES Change in Atlantic circulation could plunge Europe into cold winters Massive climate change 55 million years ago caused major disruption to ocean currents according to new research by scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. A rapid rise in global temperatures during the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) triggered many global shifts, including a reversal of ocean currents and large-scale changes in global biodiversity. Scientists are concerned that similar changes could result from modern-day global warming. Already, there is growing evidence to suggest a slow-down in North Atlantic currents that help keep Europe relatively warm. Climate change caused major disruption to past ocean currents Massive climate change 55 million years ago caused major disruption to ocean currents according to new research by scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. A rapid rise in global temperatures during the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) triggered many global shifts, including a reversal of ocean currents and large-scale changes in global biodiversity. Scientists are concerned that similar changes could result from modern-day global warming. Already, there is growing evidence to suggest a slow-down in North Atlantic currents that help keep Europe relatively warm. 45% chance Gulf Stream current will collapse by 2100 finds research New research indicates there is a 45 percent chance that the thermohaline circulation in the North Atlantic Ocean could shut down by the end of the century if nothing is done to slow greenhouse gas emissions. Even with immediate climate policy action, say scientists, there would still be a 25 percent probability of a collapse of the system of currents that keep western Europe warmer than regions at similar latitudes in other parts of the world.

|

The high-latitude freshwater cycle is one of the most sensitive barometers of the impact of changes in climate and broad-scale atmospheric dynamics because of the polar amplification of the global warming signal,” says Peterson. “It’s easiest to measure these changes in the Arctic and the better we understand this system, the sooner we will know what is happening to the global hydrologic cycle.”

The multi-disciplinary team of scientists led by Peterson calculated annual and cumulative freshwater input anomalies (deviations from expected levels) from net precipitation on the ocean surface, river discharge, net attrition of glaciers, and Arctic Ocean sea ice melt and export for the latter half of the 20th century. The scientists compared the fluxes to measured rates of freshwater accumulation in the North Atlantic during the same time period.

Their analysis showed that increasing river discharge and excess net precipitation on the ocean contributed the most freshwater (~20,000 cubic kilometers) to the Arctic and high-latitude North Atlantic. Sea ice reduction provided another ~15,000 cubic kilometers of freshwater, followed by ~2,000 cubic kilometers from melting glaciers. Together, the sum of anomalous inputs from all of the freshwater sources analyzed matched the amount and rate at which fresh water accumulated in the North Atlantic during much of the period from 1965 through 1995.

“This synthesis allows us to judge which freshwater sources are the largest, but more importantly shows how the significance of different sources have changed over the past decades and what has caused the changes,” says Peterson. “It prompts us to realize that the relative importance of different sources will change in future decades. Creating a big-picture or synoptic view of the changes in various components of the high-latitude freshwater cycle puts the parts in a perspective where we can judge their individual and collective impact on ocean freshening and circulation.”

In recent years, much attention has been given to the observed freshening of Arctic Ocean and North Atlantic and the potential impacts it may have on the earth’s climate. Scientists contend that a significant increase of freshwater flow to the Arctic Ocean could slow or halt the Atlantic Deep Water formation, a driving factor behind the great “conveyor belt” current that is responsible for redistributing salt and thermal energy around the globe, influencing the planet’s climate. One of the potential effects of altered global ocean circulation could be a cooling of Northern Europe within this century.

The team’s comparison of freshwater sources and ocean sink records revealed that over the last half century changes in freshwater inputs and ocean storage occurred not only in conjunction with one another, but in synchrony with rising air temperatures and an amplifying North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), a climatic phenomenon that has strong impacts on weather and climate in the North Atlantic region and surrounding continents, and the associated Northern Annular Mode (NAM) index.

Peterson and his colleagues contend that the interplay between the NAO and NAM, and continued rising temperatures from global greenhouse warming, will likely determine whether the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans will continue to freshen. But the scientists caution that the difficultly in predicting fluctuations in atmospheric circulation makes it impossible to know where we might be headed.

“Atmospheric modes of circulation such as the NAO and NAM exert a great deal of control on net precipitation in the ocean and even on regional temperatures, and hence ice melt as well,” says Peterson. “But what drives the NAO is the $64,000 question. Our inability to predict trends in the NAO/NAM means that, even if we could predict global warming very well, a large degree of uncertainty will remain in any forecasts of the decadal-centennial trajectories of the Arctic freshwater balance.”

This is a modified news release, “Study provides first-ever look at combined causes of North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean freshening”, from the Marine Biological Laboratory

.