‘Dead Zone’ causing wave of death off Oregon coast

‘Dead Zone’ causing wave of death off Oregon coast

Oregon State University

August 10, 2006

The most severe low-oxygen ocean conditions ever observed on the West Coast of the United States have turned parts of the seafloor off Oregon into a carpet of dead Dungeness crabs and rotting sea worms, a new survey shows. Virtually all of the fish appear to have fled the area.

Scientists, who this week had been looking for signs of the end of this “dead zone,” have instead found even more extreme drops in oxygen along the seafloor. This is by far the worst such event since the phenomenon was first identified in 2002, according to researchers at Oregon State University. Levels of dissolved oxygen are approaching zero in some locations.

“We saw a crab graveyard and no fish the entire day,” said Jane Lubchenco, the Valley Professor of Marine Biology at OSU. “Thousands and thousands of dead crab and molts were littering the ocean floor, many sea stars were dead, and the fish have either left the area or have died and been washed away.

“Seeing so much carnage on the video screens was shocking and depressing,” she said.

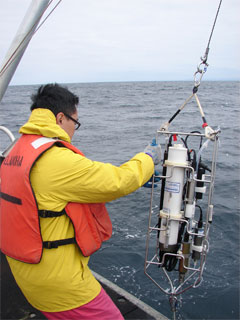

Francis Chan, member of the Partnership for Interdisciplinary Study of Coastal Oceans, brings up a sample aboard the Elahka in this July 25, 2006, photo. Image courtesy of Oregon State University. Hypoxic “dead zone” growing off the Oregon Coast |

OSU scientists with the university-based Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans, in collaboration with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, used a remotely operated underwater vehicle this week to document the magnitude of the biological impacts and continue oxygen sampling. This recent low-oxygen event began about a month ago, and its effects are now obvious.

Any level of dissolved oxygen below 1.4 milliliters per liter is considered hypoxic for most marine life. In the latest findings from one area off Cape Perpetua on the central Oregon coast, surveys showed 0.5 milliliters per liter in 45 feet of water; 0.08 in 90 feet; and 0.14 at 150 feet depth. These are levels 10-30 times lower than normal. In one extreme measurement, the oxygen level was 0.05, or close to zero. Oxygen levels that low have never before been measured off the U.S. West Coast.

“Some of the worst conditions are now approaching what we call anoxia, or the absence of oxygen,” said Francis Chan, a marine ecologist with OSU and PISCO. “This can lead to a whole different set of chemical reactions, things like the production of hydrogen sulfide, a toxic gas. It’s hard to tell just how much mortality, year after year, these systems are going to be able to take.”

One of the areas sampled is a rocky reef not far from Yachats, Ore. Ordinarily it’s prime rockfish habitat, swarming with black rockfish, ling cod, kelp greenling, and canary rockfish, and the seafloor crawls with large populations of Dungeness crab, sea stars, sea anemones and other marine life.

This week, it is covered in dead and rotting crabs, the fish are gone, and worms that ordinarily burrow into the soft sediments have died and are floating on the bottom.

The water just off the bottom is filled with a massive amount of what researchers call “marine snow” — fragments of dead pieces of marine life, mostly jellyfish and other invertebrates. As this dead material decays, it is colonized by bacteria that further suck any remaining oxygen out of the water.

“We can’t be sure what happened to all the fish, but it’s clear they are gone,” Lubchenco said. “We are receiving anecdotal reports of rockfish in very shallow waters where they ordinarily are not found. It’s likely those areas have higher oxygen levels.”

The massive phytoplankton bloom that has contributed to this dead zone has turned large areas of the ocean off Oregon a dirty chocolate brown, the OSU researchers said.

Scientists observed similar but not identical problems in other areas. Some had fewer dead crabs, but still no fish. In one area off Waldport, Ore., that’s known for good fishing and crabbing, there were no fish and almost no live crabs.

The exact geographic scope of the problem is unknown, but this year for the first time it has also been observed in waters off the Washington coast as well as Oregon. Due to its intensity, scientists say it’s virtually certain to have affected marine life in areas beyond those they have actually documented.

This is the fifth year in a row a dead zone has developed off the Oregon Coast, but none of the previous events were of this magnitude, and they have varied somewhat in their causes and effects. Earlier this year, strong upwelling winds allowed a low-oxygen pool of deep water to build up. That pool has now come closer to shore and is suffocating marine life on a massive scale.

Some strong southerly winds might help push the low-oxygen water further out to sea and reduce the biological impacts, Lubchenco said. The current weather forecast, however, is for just the opposite to occur and for the dead zone event to continue.

There are no seafood safety issues that consumers need to be concerned about, OSU experts say. Only live crabs and other fresh seafood are processed for sale.

Researchers from OSU, PISCO and other state and federal agencies are developing a better understanding of how these dead zone events can occur on a local basis. But it’s still unclear why the problem has become an annual event.

Ordinarily, north winds drive ocean currents that provide nutrients to the productive food webs and fisheries of the Pacific Northwest. These crucial currents can also carry naturally low oxygen waters shoreward, setting the stage for dead zone events. Changes in wind patterns can disrupt the balance between productive food webs and dead zones.

This breakdown does not appear to be linked to ocean cycles such as El Niño or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation.

Extreme and unusual fluctuations in wind patterns and ocean currents are consistent with the predicted impacts of some global climate change models, scientists say, but they cannot yet directly link these events to climate change or global warming.

This is a modified news release from Oregon State University.