Weight of flooded Amazon river causes Earth to sink 3 inches

Ohio State University news release

October 5, 2005

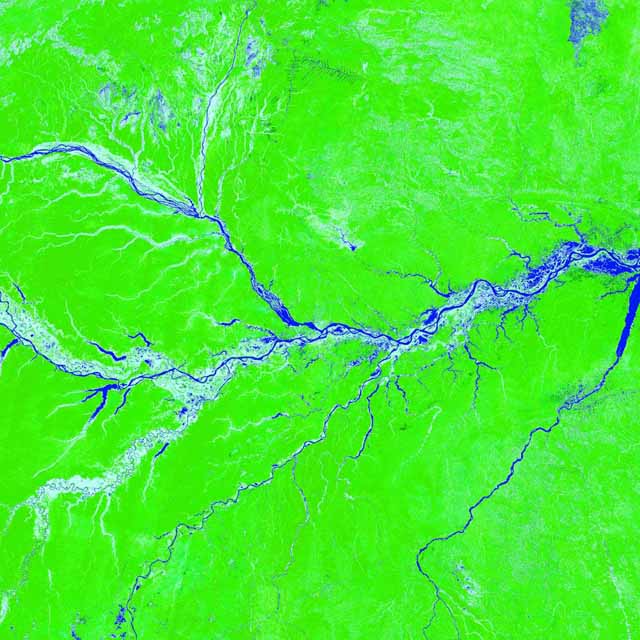

A topographic map of a section of the central Amazon River Basin near in Manaus, Brazil. Dark blue indicates channels that always contain water, while lighter blue depicts floodplains that seasonally flood and drain, and green represents non-flooded areas. Image courtesy of the Global Rain Forest Mapping Project.

COLUMBUS , Ohio As the Amazon River floods every year, a sizeable portion of South America sinks several inches because of the extra weight and then rises again as the waters recede, a study has found.

This annual rise and fall of earth’s crust is the largest ever detected, and it may one day help scientists tally the total amount of water on Earth.

“What would you do if you knew how much water was on the planet?” asked Douglas Alsdorf, assistant professor of geological sciences at Ohio State University. “That’s a really exciting question, because nobody knows for sure how much water there is.”

Having an estimate of Earth’s entire fresh water cache from hidden groundwater, to the world’s rivers and wetlands, to mountaintop glaciers would greatly improve our ability to predict drought, flooding and climate change.

The study appears in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The study began in 2004 after Michael Bevis, now an Ohio Eminent Scholar and professor of civil and environmental engineering and geodetic science at Ohio State, detected an up-and-down motion at a global positioning system (GPS) station he’d placed in the ground near a lake in the Andes. He concluded that as the water level in the lake rose and fell, the ground nearby moved in response. At the time, he was a professor at the University of Hawaii.

Bevis began to look for similar oscillations in data recorded by other GPS stations around South America. Other scientists had already reported detecting such changes up to half an inch in other parts of the globe, but they suspected that the greatest motion would occur beneath the Amazon River Basin, the largest river system in the world. In late 2004, one group used satellite data to predict that the bedrock beneath the Amazon would rise and fall about one inch every year.

But when Bevis looked at the data from a GPS station in Manaus, Brazil near the center of the river basin he saw not a one-inch change, but three inches.

|

He recruited Alsdorf to help him couple his data to a computer model of water flow through the basin. They used a very simple approach colloquially called a “bathtub model,” which assumed that the water level rose and fell uniformly across the Amazon, like running water in a bathtub.

They used a simple model because scientists know relatively little about the Amazon River Basin, Alsdorf explained. Its sheer size approximately equal to the continental United States, with a flood area the size of Texas hinders detailed study.

Like many researchers, they suspect that the amount of water that flows through the Amazon into the Atlantic Ocean every year is about ten times larger than that carried by the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico.

“The old joke is, we know the discharge of the Amazon, give or take the Mississippi,” Alsdorf said.

With colleagues in the United States and Brazil, Bevis and Alsdorf merged the water model and the GPS data to show that between 1995 and 2003 the bedrock around Manaus rose and fell in a regular pattern that coincided with the basin’s annual flood. The bedrock sank slowly as the floodwaters gathered, then rose back up as the waters receded. The average change in height was about three inches.

Alsdorf was quick to point out caveats of the study. The researchers have data for only one GPS station, and the “bathtub model” is greatly simplified compared to the natural variability in water level throughout the Amazon. What’s more, scientists aren’t exactly sure of the composition of the bedrock beneath the basin.

Despite the uncertainties of the study, the three-inch oscillation is the most dramatic measured to date, and it’s the first known recording of a land mass oscillating in response to the flow of a river.

It also raises the possibility that scientists could one day calculate the amount of water in the Amazon that is, they could “weigh” the river system based on how much it makes the earth sink.

Similar techniques could be used to calculate the amount water on the planet, but much more data would be needed from all over the globe, Alsdorf said.

As a first step, he and his colleagues want to install more GPS stations around Manaus and the rest of the Amazon to see if the sinking varies by location. He suspects that similar effects could also be detected in the Congo River system in Africa.

But to monitor water flow worldwide would require a satellite, and Alsdorf leads the American portion of an international team that is proposing a new satellite to do just that. The Water Elevation Recovery (WatER) mission would use radar to measure global water levels every eight days.

Data from WatER would give scientists a better estimate of fresh water storage and river discharge, and improve models of the global water cycle and climate change, he said.

Coauthors on the Geophysical Research Letters paper included Eric Kendrick, senior research associate in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Geodetic Science at Ohio State; Luiz Paulo Fortes of the Institute Brasilieiro de Geographia e Estatística in Brazil; Bruce Forsberg of the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonas in Brazil; Robert Smalley Jr. of the University of Memphis; and Janet Becker of the University of Hawaii.

Contact:

Douglas Alsdorf, (614) 247-6908; Alsdorf.1 -at- osu.edu

Michael Bevis, (614) 247-5071; Bevis.6 -at- osu.edu

Written by Pam Frost Gorder, (614) 292-9475; Gorder.1 -at- osu.edu

This is an adapted news release from Ohio State University. The original version can be found at EARTH SINKS THREE INCHES UNDER WEIGHT OF FLOODED AMAZON