A photo essay

|

Madagascar has been called the great red island and from space, astronauts have remarked the island looks like it is bleeding to death. Soil conditions and poorly vegetated hillsides mean Madagascar loses more topsoil per hectare than any country in the world. Being one of the poorest nations on Earth, the people of Madagascar can ill afford this loss. In 2004 I set off to see one of the rivers that is carrying away the island’s soils; the Manambolo of Western Madagascar.

Antananarivo

The journey begins in the capital city of Antananarivo, better known as “Tana.” Tana is located in the central highlands of Madagascar where the climate is mild and the people — called the Merina — look ethnically Indonesian. Tana is quite like any city I have ever visited, with colorful houses decorating the hillsides, extensive rice paddies runing through sections of the town, and bustling streets full of cars and Zebu-drawn carts.

With the help of an outfitter I charter a Cessna and head west with my Tana-based guide, Benja, and our pilot. With the help of an outfitter I charter a Cessna and head west with my Tana-based guide, Benja, and our pilot. We fly over a largely forest-less landscape pockmarked with lavaka, deeply eroded gullies that bleed red laterite soils into creeks and rivers. While lavaka is often cited as a consequence of deforestation, they are primarily formed as a result of other factors and vegetation clearing is now believed to play a secondary role in the expansion of such gullies.

After about an hour and a half of this the landscape changes and we pass over a large valley. Here we have the first sighting of the river that will be our home and mode of transportation for the next few days, the Manambolo. The Manambolo river originates in the highlands of Madagascar (“Haut plateau”), about 80 miles (130 km) west of Tana. The Manambolo, deep red-orange in color from eroded sediment, descends through a largely deforestated landscape as it heads toward the Mozambique Channel.

We fly beyond the Manambolo, past a landscape dotted with plumes of smoke from land-clearing fires, over Bemaraha National Park. Bemaraha is one of Madagascar’s newest parks — it was opened to the public only in 1998. The 152,000ha Bemaraha is best known for its tsingy — sharp limestone pinnacles that may reach 150 feet in height. Flying over the tsingy is a quite an experience [video]. The pilot dives so low that we are just barely clearing the sharp spires and we see sifaka lemurs and birds scattering from the trees. After a couple of flyovers we head east toward the landing strip outside a satellite village of the town of Ankavandra.

As we come in for our approach to the grassy landing field children sprint from their huts knowing that a vazaha — the non-pejorative term for a white foreigner — is soon to arrive.

Sure enough, upon landing a couple dozens kids mob the plane. It is immediately evident that this is an unforgiving land. Despite their bright eyes, beaming smiles, and playful nature most of the children look undernourished. They are slender and small for their age and many of the children show signs of illness. Their condition is not unusual for the country; about 70 percent of Madagascar’s population lives below the poverty line while nearly half of its children under five years of age are malnourished.

We hire a couple of porters from the village to help with the gear and make arrangements with two canoemen, Betsara (age 28) and Max (age 26). As we load the boats I practice my Malagasy — the native toungue of Madagascar as well as the name for the people of the country — with some of the kids who want to be involved in the action.

On the river

Our pirogues, supplied by a tour operator that specializes on Manambolo river trips, are about 13 feet (4 meter) long and are naviagable in water less than an foot deep — something which is important given the low level of the river at this time of year.

cliffs which are striated with layers of white, red, and green clays. Sometimes we pass by children along the river banks and there are scattered huts. At one point we pass a pirogue with three boys, one of whom is playing a song with a string guitar as the other two sing along in perfect harmony.

We see a number of birds including the colorful Malagasy kingfisher (Alcedo vintsioides), the Madagascar bee-eater (Merops superciliosus), the Black kite (Milvus migrans), ducks, herons, the Pied crow (Corvus albus), and others.

We camp on a giant sandbank. As night falls we are besieged by thousands on insects — large gnat-like miseries, thumbnail-sized black beetles that have an affinity for hair, and buzzing but dim-witted cicadas. These flock around our meager light source — our candles — and are drawn to the light reflecting off my light skin and my rice. I get a full week’s allowance of chitin — the material from which an insect’s exoskeleton is formed — from the creatures in my meal. After a lively discussion in broken English and Malagasy on politics and the realities of life in America, I head for the refuge of the tent.

Day two: Bandit concerns

Back on the river we encounter a young Nile crocodile. The Manambolo was once full of crocodiles but due to hunting for their skins they are now considered a threatened species in Madagascar. Here water levels are too low to support adult crocs but lower down the river, below the canyon, crocodiles are still abundant.

We stop at Tsianaloka, a village consisting of around ten huts. It is apparent that the childen here do not see many foreigners (vazaha). Many of the kids are thin and some have signs of malnutrition. No one I meet in the village, including the young adults, knows their age.

We stop for lunch under a grove of mango trees, behind which there is burned out scrubland and ash littering the ground. Betsara and Max talk with some men passing in a pirogue. Afterwards Betsara and Max seem a bit unsettled but it is not readily apparent over what they are concerned. We press onward and battle a fierce wind before Betsara indicates we should pull off the river.

As we attempt to set up the tents in the wind — an unsuccessful endeavor for the moment — Benja explains the reason for the uneasiness: the Dahalo may be in the area planning an ambush.

The Dahalo are bandits usually found in mountainous regions of Madagascar. Their preferred target is Zebu cattle but will take almost anything when they raid villages and ambush people traveling by foot or pirogue. The Dahalo are typically armed with shotguns and carefully plan their attacks. Like the Kamajors of West Africa, the Dahalo rely an on elaborate pre-raid ritual which they — and local people — believe makes them invinceable to bullets. Villagers are easy targets for these bandits because of their isolation, beliefs strongly rooted in tradition, and lack of weapons, and the Dahalo count on intimidation to keep villagers from taking effective protective actions. Police are said to avoid the outer areas where the Dahalo prey, either being paid to stay away or fearing for their safety. The Dahalo are an amorphous group and it is likely that some are often members of the very communities they raid. In some areas a man is required to steal a neighbor’s Zebu before he can take a woman’s hand in marriage.

Max and Betsara were attacked by the Dahalo a few weeks past. The bandits took all their cooking supplies and warned them not to guide vazaha down the river. It is said that they only thing the Dahalo fear are vazaha believing them to have superior weapons. Nevertheless it is a tense night and we take turns keeping watch. The wind and blowing sand adds to the discomfort — sand for dinner and in hair and eyes — but we are able to set up one tent behind a barricade dug in the sand and protected by the canoes.

At night the sand comes alive with insects. There are giant 2-inch (5 cm) plus crickets, small yellow scorpions, enormous earwigs, and plethora of other arthropods.

Day three: Entering the canyon

In the morning we have sand in everything. It’s almost like if has snowed. The plethora of insect life from the previous night has taken refuge in all our equipment and we’re frequently surprised by strategically hidden scorpions as we pack.

At breakfast we’re joined by a local Sakalava boy who’s finely dressed. He tells us that the Dahalo had crossed the river and appeared to be preparing an ambush in the late afternoon. Thus the concerns of Max and Betsara were warranted and they plan to take special precautions on their return trip upriver.

As we move downstream the landscape becomes more canyon-like. Increasingly there are little pockets of forest and we encounter more local people on the river.

We pass some fasana or tombs constructed with neatly piled rock. These are tombs of the Sakalava, the ethnic group that lives in this region and most of western Madagascar. In the distance there is a mountain where local people have typically buried their dead. Once you pass the mountain it becomes a serious fady or taboo to point with your finger — you need to point with your knuckle, paddle, or elbow when trying to call attention to something. Pointing with your finger angers the razana or spirits of the dead and offenders must make an offering.

We reach the Manambolo canyon and it is spectacular with colorful cliff walls and deciduous forests. We camp at a picturesque spot where a clearwater stream enters the muddly flow of the Manambolo. As we unload the pirogues bright yellow and teal butterflies flutter about and black kites circle above.

I go for a walk up the clearwater creek (“Oly” creek) and find a gorgeous pool full of at least 5 kinds of fish including a silverside-like fish with black markings on its tail, a goby-like creature, and three types of cichlids (a sand-colored species with vertical bands, a dark cichlid, and an opaline type with red fins and occasionally yellow or orange flanks). Seeing these fish is a special experience; Malagasy cichlids are increasingly endangered due to habitat loss and degradation from deforestation and soil erosion. Additionally, the introduction of exotic species — specifically Tilapia — have absolutely decimated native fish stocks. In some rivers as much as 99% of the fish collected in surveys are now Tilapia species and several of Madagascar’s unique cichlids are no longer recorded in the wild.

While walking back to the camp site I see a group of Decken’s sifaka leaping about in trees high up on the ridge above our tents. We watch these lemurs as the sun sets.

Lemurs, a group of primates found only on Madagascar, are today highly threatened by habitat loss and hunting. Many of the island’s lemur species have gone extinct since the arrival of humans less than 2000 years ago.

Day 4: Exploring Oly Canyon

In the morning Betsara, Benja and I hike up Oly Canyon creek. The creek runs over white limestone rock, through channels and shoots, and over small waterfalls into turqoise pools. We are surrounded by pristine deciduous forests, orange and yellow blossomed trees, and calls of birds. We encounter a group of red-fronted brown lemurs that have come down to the river to drink. They grunt at us as we continue upstream through palm-lined pools full of exquisite Madagascar lace plant (Aponogeton madagascariensis) in bloom and other aquatic plants.

We find many skinks, a couple frogs, and a mass of glowing red beetles. In the creek there are small shrimp, purple crabs, and 6-8″ (15-20 cm) long cichlids. There are hundreds of snail shells in various shapes and sizes along with living black snails clinging to rocks in the rapid sections of the river.

After a couple hours of walking we come to an obscenely beautiful place, a 20 foot waterfall pouring into a blue pool. We spend some time swimming in the pool and jumping off the falls. On the way back I stop to swim in some of the natural pools.

We press further down the river through the canyon and past several waterfalls and another group of red-fronted brown lemurs. The canyon continues to be gorgeous.

We see more locals in the lower part of the canyon. Some are visiting the remains of their ancestors while others are tending to their river-side rice patches. We stop to spend a few minutes talking with a family growing rice on a sandbar. The family will stay long enough to grow one crop of rice before the river levels rise and inundate the sandbar.

Rice is the staple of the Malagasy diet and most people in Madagascar eat rice three times a day. Madagascar once grew enough rice to feed itself but environmental degradation and resulting soil erosion has diminished the country’s agricultural capacity. Today Madagascar relies on imports from other countries to feed its population.

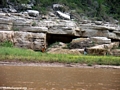

Towards the village of Bekopaka the wind picks up significantly right as we hit a long stretch of slackwater. We make slow progress through an area that is interesting geologically with limestone slabs pancaked atop oneanother and then eroded by the river. These create bizarre rock formation and caves.

The village of Bekopaka is our destination. Here we’ll camp and then visit the limstone tsingy up close. As we drag our gear across the sand bar and up to our campsite I can’t help but think about the beauty of the canyon. I’m already salivating at the idea of returning to explore more of the Manambolo’s side canyons and creeks. Visiting a place like the Manambolo reminds you that there are wildlands worth protecting.

The Manambolo Team

|

Betsara, 28 years old, canoe man & cook | ||

|

Max, 26 years old, canoe man | ||

|

Benja, 28 years old, the rainmaker | ||

|

Rhett, 26 years old |

Related links:

Seeking the world’s strangest primate on a tropical island paradise – In Search of the Aye-aye on Nosy Mangabe