- Rubber plantations replaced over 110,000 hectares of forests identified as key biodiversity areas and protected areas between 2005 and 2010.

- “Low rubber prices, combined with the risk of plantation failure or damage in environmentally marginal areas can have devastating economic consequences for small-land holders.”

- Researchers predict that by 2020, almost 640,000 hectares of protected areas will be converted to rubber monocultures.

Your car tires may be treading over forests and wildlife in Southeast Asia.

As the global demand for tires soars, so does the demand for natural rubber sourced from Hevea brasiliensis, the para-rubber tree. This rising demand is driving a rapid expansion of rubber plantations into biodiversity-rich forests and croplands of Southeast Asia, according to a new study published in Global Environmental Change.

Between 2005 and 2010, for instance, rubber plantations replaced over 110,000 hectares of forests identified as key biodiversity areas and protected areas, the authors write.

“I think it’s very alarming,” William Laurance, a professor and conservationist at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, who was not involved in the study, told mongabay.com. “Rubber is spreading rampantly in Southeast Asia-sort of a ‘second tsunami,’ following the explosive expansion of oil palm plantations in the region. I’ve personally seen vast swaths of native forest being converted into rubber plantations in southern China, Malaysia, and Cambodia.”

Researchers from China, Singapore, UK and the U.S. evaluated where rubber occurs naturally, and examined the extent to which rubber plantations have spread in Southeast Asia – where nearly 97 percent of the world’s rubber is grown. This includes non-traditional areas where rubber was not historically grown, and where environmental conditions are not suitable for cultivation of rubber.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study that provides a quantitative region-wide overview of the extent and trends of rubber plantation expansion into biophysically marginal environments,” said Antje Ahrends, a researcher at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and the World Agroforestry Centre, and lead author of the study.

Rubber production in Southeast Asia increased from 300,000 metric tons in 1961 to over 5 million metric tons in 2011, a jump of more than 1,500 percent, the authors write. Most of this rubber production today is through monocultures. Traditionally, this was not the case.

Rubber would usually be grown with timber trees, fruit trees, and other crops, Ahrends explained. “These rubber agroforests structurally resemble secondary forests.”

On the other hand, rubber monocultures are structurally uniform and there is generally heavy application of fertilizers and pesticides, she added.

“Research has shown that mixed rubber agroforests are of higher value for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem functioning than rubber mono-cultures, and of course they broaden income sources for farmers,” Ahrends said. “However, they are unfortunately also less productive.”

Predictably, rubber agroforests are being increasingly replaced by rubber monocultures to increase productivity and, in turn, profit. And as monocultures expand, they eat into areas that are not conducive for rubber cultivation.

By analyzing rubber production in Southeast Asia, Ahrends and her colleagues found that while over half of the world’s rubber is produced in the continental portion of the region north of Thailand, only 1.5 percent of that area has environmental conditions actually suited for rubber.

Since 2005, for example, the team found that rubber plantations have increasingly spread to sub-optimal areas that are at higher altitudes, on steeper slopes, are more likely to experience frost conditions and are subject to longer dry periods. In fact, by 2010, almost 2 million hectares of plantations were located in such marginal areas, the authors write, the largest of these shifts occurring in Myanmar, Vietnam and China.

But shifts into such marginal regions have increased the risk of rubber plantation failure due to severe environmental events like typhoons or droughts. For instance, in 2013, typhoons destroyed more than $250 million worth of rubber plantations in Vietnam, the authors write.

“Restoration and recovery from plantation damage through typhoons may take three to seven years and lead to significant income lags,” Ahrends said. Moreover, “low rubber prices, combined with the risk of plantation failure or damage in environmentally marginal areas can have devastating economic consequences for small-land holders.”

However, breeding programs have developed rubber crops that have increased tolerance to sub-optimal environmental conditions. But even such developments, Ahrends said, are not enough.

“Evidence-to-date suggests that the tolerance gains are not sufficient to safeguard against crop failures in these extreme environments,” she said. “Many farmers have learned this the hard way – for example, during the recent rubber price boom high-elevation tea farmers in Southern China began to convert their land to rubber. However, the slow tree growth in these areas has frequently precluded harvest.”

Planting rubber on marginal lands can have other ecological consequences too. For example, planting rubber plantations on steep hillsides can increase soil erosion, the authors write. Moreover, the increased use of fertilizers on degraded soils can reduce water quality, they add.

Encroaching into biodiversity-rich areas

Rubber plantations are not only expanding into sub-optimal areas, but are also cutting into vast swaths of forests and cultivated land.

Between 2005 and 2010, for instance, nearly 250,000 hectares of land with natural vegetation was cleared for rubber plantations. Rubber plantations also encroached upon over 60,000 hectares of protected areas.

The reason for the rampant conversion of forest lands to rubber is simply the high profitability of the crop when prices are high, Ahrends said.

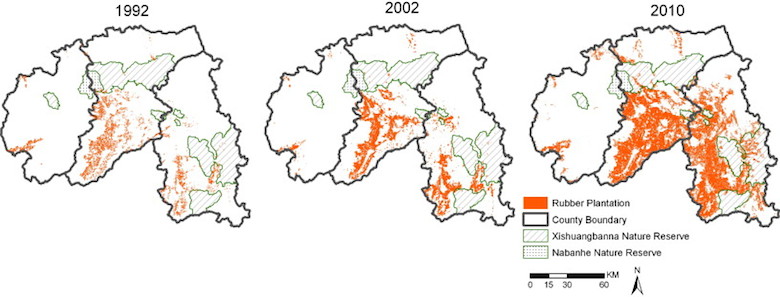

China is a major case in point. As China’s demand for cars grew, so did the conversion of biodiversity-rich forests into rubber monocultures. Xishuangbanna, located at the southwest corner of Yunnan Province in China, for example, saw a rapid expansion of rubber plantations, encouraged by various government incentives and subsidies.

Covering about 87,000 hectares of land in 1992, rubber plantations in Xishuangbanna quickly spread to 424,000 hectares in 2010, according to a study published in Ecological Indicators. And the fast pace of the expansion has wiped out most of Xishuangbanna’s forests.

Researcher Jianchu Xu of the World Agroforestry Centre in China, and his colleagues, write in the paper that “across much of the landscape, there is little to virtually no natural forest of any kind left outside Xishuangbanna’s nature reserves. Some areas of plantation can even be found inside reserve boundaries.” Jianchu Xu is also a co-researcher with Ahrend.

According to the Global Forest Watch forest monitoring platform, Xishuangbanna lost approximately 93,000 hectares of tree cover from 2001 through 2013, representing about 5 percent of its area. Of that, nearly 11,000 hectares were lost from official protected areas. Click to enlarge.

Rubber has replaced natural forests in Cambodia and Laos as well, according to another study published in Conservation Letters. For instance, over 70 percent of the 75,000-hectare Snoul Wildlife Sanctuary in Cambodia was cleared for rubber during 2009-2013, the authors write.

In fact, based on rubber expansion targets, Ahrends and her team predict that by 2020, almost 640,000 hectares of protected areas –mostly in Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam – will be converted to rubber monocultures.

While devastating for Southeast Asia’s biodiversity, rubber has been very lucrative for many farmers. But this will last only as long as rubber prices are high and the plantations produce reliable yields, Ahrends told mongabay.com.

“Rubber price is volatile and in marginal environmental areas there is the possibility of plantation failure,” she said. “This exposes small-scale farmers to economic risk.”

Moreover, moving away from cultivating a diverse range of crops to rubber monocultures also threatens food security. By doing so, the farmers are narrowing their potential income sources, and they become dependent upon global market prices, Ahrends explained.

So can rubber plantations expand in a way that balances the need for increased rubber yield, improved farmer livelihoods, as well as biodiversity conservation?

According to Laurance, establishing rubber plantations on land that has already been cleared is still fine. “In those cases, the planted trees can help to stabilize soils, reduce erosion, and increase carbon storage,” he said. “Their benefits for biodiversity are often much less than native forests but it’s certainly better than having just cleared or degraded land, and of course the trees have economic benefits for landowners.

“However, clearing native forests for rubber, especially in areas where the climate and soils are marginal, seems foolish to me. The biodiversity and environmental costs are very high, and the economic benefits are likely to be modest at best. And with increasing climate change the picture for rubber in marginal areas could become even worse.

“The take-home message is simple,” said Laurance. “Whenever and wherever possible, don’t clear native forests or key wildlife habitats to plant exotic plantations. Plantations, whether they be rubber, oil palm, or another exotic species, are often biological deserts.”

Citation: Antje Ahrends, Peter M. Hollingsworth, Alan D. Ziegler, Jefferson M. Fox, Huafang Chen, Yufang Su, Jianchu Xu. Current trends of rubber plantation expansion may threaten biodiversity and livelihoods. Global Environmental Change, 2015; 34: 48 DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.002