- Asia is home to a vast array of primates and other mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds and fish — all fascinating, all uniquely adapted to their habitats. Many are seriously threatened, but little known by the public.

- One conservation argument says that protecting charismatic species like tigers, rhinos and orangutans and their habitat will also protect lesser known species such as pangolins, langurs and the Malayan tapir. But this is a flawed safety net through which many little known species may fall into oblivion.

- Over the next six months, Mongabay will introduce readers to 20 Almost Famous Asian Animals — a handful of Asia’s little known fauna — in the hope that familiarity will help generate concern and action.

- In this first overview article, we rely as much on pictures as on words to profile some of Asia’s most beautiful, ugly, strange, magnificent and little known animals.

This is the first of 20 Mongabay stories highlighting Almost Famous Asian Animals — all to be published by the end of 2016. You can find the complete Almost Famous series here.

Try to name Asia’s most endangered animals, and iconic species such as tigers, orangutans and rhinos likely leap to mind. But pangolins, langurs or saola? Not so much. Most of us haven’t heard of these “other” species, and can’t even picture them.

Yet these little-known primates and other mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds and fish are no less valuable to their habitats, and to earth’s overall biodiversity, than their more famous, more charismatic Asian animal compatriots.

But unfortunately for these lesser-known creatures, they face the same deadly threats as the “top” tier endangered species. They walk the same paths, use the same rainforest trees and mangrove swamps, and drink from the same rivers. They depend on the same ecosystems, and those ecosystems depend on them.

So when habitats are logged, fragmented by roads, polluted, or taken over by oil palm plantations, their survival is just as perilous as for the “big name” species.

Each species’ loss slashes yet another thread from the web of life, and threatens to leave that rich weave hanging in tatters. Despite the urgent need, Asia’s Almost Famous receive little attention, and even less money for research and conservation.

The leaky umbrella problem

A popular conservation argument runs this way: programs aimed at saving “celebrity” species such as orangutans in the wild also must protect their habitat. This preserved habitat then acts like a giant umbrella, which, in turn, hopefully helps shield all the other minor celebrities and total unknowns who share the same forests, swamps and estuaries over which the big name species roam.

Unfortunately, that “one size fits all” approach presumes a lot. All too often these habitat umbrellas leave many species out in the rain — living in biodiverse habitats that lack charismatic megafauna. Or the habitat umbrella leaks like a sieve — with tigers protected, but gibbons still at the top of the bushmeat menu.

The problems for Asia’s Almost Famous Animals are many. Often, scientists don’t even know how many of a particular species are left in the wild, let alone where and how they live, what they eat and when they breed — there just isn’t enough money to do the needed research.

Because we don’t know much about these creatures, conservationists don’t know if some critical lifestyle detail is being overlooked — a detail that may be crucial to long term survival, and whose absence will drop them into the abyss of extinction.

Such gaps in our collective knowledge may present themselves in the same moment a new species is discovered. Often, by the time scientists find a new animal, the species is already gravely threatened and its rescue becomes a race against time, lack of data and lack of funds.

One needn’t look far for examples of such dire conservation conundrums: scientists found an astounding trove of new species unknown to science less than four years ago in Southeast Asia’s Greater Mekong region — a discovery that included 28 reptiles, 24 fish, 21 amphibians, three mammals and a bird, 367 new species in all, each with fascinating traits and life histories.

The list included the “scribbled arowana” (Scleropages inscriptus), a dragon fish from Myanmar with intricate, maze-like markings on every scale; and the Sweet Singing Frog (Gracixalus quangi) from the high-altitude forests of northern Vietnam, whose every song to attract females appears to be a new composition, with improvisational clicks, whistles and chirps instead of repetitive croaks.

Also numbered among the newly discovered was the red-and-white furred Laotian giant flying squirrel (Biswamoyopterus laoensis), about which we know little today, except that it was first documented by researchers in a bushmeat market. B. laoensis had barely stepped out onto the global biodiversity stage, when scientists realized that it was under threat from overexploitation and a fast shrinking habitat.

All too often, Almost Famous endangered species share certain fatal characteristics in common: they may taste delicious, make cuddly pets, and/or live in areas coveted by loggers and agribusiness, or by the rapidly growing human population of Asia.

The frightening reality is that many Almost Famous species could disappear before we get to know anything about them — including that they exist.

What follows is a brief survey of some of Asia’s Almost Famous — a list of species that runs into the thousands of primates and other mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds and fish — Asian animals on the brink:

A sampling of “should-be” famous primates

Over 70 percent of Asia’s primates are threatened with extinction due to the burning and clearing of tropical forests for agriculture and other development, the hunt for food by expanding human populations, and the illegal wildlife trade for traditional medicine and pets, according to the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group. That proportion is even higher in Southeast Asia. In Vietnam and Cambodia, for example, 90 percent of primates are at risk.

Gibbons: All 19 of the species of gibbon, a classification only known to Asia, are threatened. These species are often categorized as “lesser apes,” which only means that they are smaller in size than the so-called “great apes”. Four gibbon species are classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List, 13 are Endangered, one is Vulnerable, and the last (the Northern Yellow-cheeked Crested Gibbon) is newly discovered, so not yet assessed.

Vietnam has some of the world’s rarest. There are, for instance, only 100 Eastern Black Crested gibbons (Nomascus nasutus). The Northern White-cheeked Crested Gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) is also Critically Endangered, with the majority of the tiny population found in just one place: Pu Mat National Park, part of the Western Nghe An Biosphere Reserve.

The White-handed Gibbon (Hylobates lar) ranges more widely, from northern Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia to Myanmar, Thailand and southern China. The species is known for its Olympic-level gymnastics, as it swings boldly from tree to tree. The animals are also masterful singers, making distinctive whoops to warn of threats, with different notes used to distinguish each type of predator.

Langurs: Southeast Asia is known for its many monkeys. Take for example the Cat Ba or Golden-headed Langur (Trachypithecus poliocephalus poliocephalus), one of the world’s most Critically Endangered primates. It is endemic to the limestone cliff forests of the island of Cat Ba in northern Vietnam, and is a cave dweller. The animals, always on the move, sleep just a night or two in one cave before moving on to another.

In the 1960s, there were around 2,500 Cat Ba Langurs, but poaching cut their numbers to just 53 by 2000. Thanks largely to the Cat Ba Langur Conservation Project, which stopped the hunting, hired guards, monitored populations and established a special sanctuary, numbers are now increasing. Latest estimates put their population at 67, a qualified success story that demonstrates how Almost Famous species, when given proper attention, can begin the long climb to recovery.

The Cat Ba langur is far from the only langur that’s endangered. Over the last 30 years, Red-shanked Douc langurs (Pygathrix nemaeus) experienced a 50 percent drop in their population, with similar declines predicted for the future.

Often called the most beautiful of the monkeys, Red-shanked Douc langurs have wise-looking, golden faces with long white hair sprouting from their cheeks. They’re found in the forests of Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos, where war in the 1960s and 70s — with its napalm bombing — decimated populations, and where today deforestation and capture for the pet and medicinal trades threaten to finish the job.

Lorises: All of Asia’s lorises are under threat. There are two kinds: slow and slender. Slender lorises are found in India and Sri Lanka, while slow lorises live in and around Southeast Asia.

Lorises are nocturnal, arboreal primates with extremely strong fingers and toes. Habitat loss has decimated populations, but even worse has been the high demand for them as pets, as tourist photo props, as fashion accessories — body parts are sometimes made into key rings — and for the medicinal trade.

Slow lorises are the world’s only venomous primate. When threatened, they lick toxin-producing glands on the inside of their elbows and then they bite. Wildlife traders avoid the bites by pulling or cutting out the animal’s teeth, which in turn leads to infection and an inability to eat or participate in social grooming.

Slow lorises were once categorized as a single species, but scientists have now distinguished five to eight separate ones. The Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus), for example, is found in small, isolated populations only on the Indonesian island of Java, and was considered a subspecies until recently. It’s now listed as Critically Endangered thanks to the loss of at least 80 percent of its habitat over the last 20 to 30 years — a reminder of just how fast Asia is changing.

More mammals on the brink

Pangolins: About 100,000 illegally traded pangolins (mammals of the order Pholidota) are seized every year by law enforcement, making it arguably the most trafficked mammal in the world. No one knows how many hundreds of thousand more are traded undetected by the authorities.

Pangolins are scaly anteaters about the size of a house cat, described by imaginative writers as mini-stegosauruses, walking pinecones, and even artichokes with feet. The name comes from the Malay word penggulung, which means “roller” and describes the animal’s primary defense: it rolls itself up into a ball — a great tactic for fending off animal predators, but not so useful for traffickers who just pick up the inert spheres and pop them in a bag.

There are eight pangolin species — four in Asia (the Chinese, Indian, Sunda and Philippine pangolin) and four in Africa (the tree, long-tailed, giant, and Temminck’s ground pangolin). All are endangered due to demand for their meat and scales, used in traditional medicine. They’re a big money maker: a single Sunda pangolin yields about 900 to 1,000 scales which can sell for $3,000 per kilogram, pangolin meat (a delicacy) can go for $300 per kilogram, and live pangolins pay out nearly $1,000 each.

Pangolins are important for pest control, with a single adult consuming roughly 70 million insects a year. They do poorly in captivity due to their highly specialized diet of live ants and termites, so they’re rarely seen in zoos.

Asian tapir: Imagine a tapir and likely the three Latin American varieties come to mind. But it is the fourth, the Endangered Asian (or Malayan) tapir (Tapirus indicus), that is the largest of them all, and the only tapir species from Asia.

Scientists don’t know how many Asian tapirs exist, but they estimate that 2,000 may still survive in Malaysia, with just 50 in Sumatra, maybe 100 in Thailand, along with a few isolated populations in Myanmar.

Like others in their clan, the Asian tapir has a short, fleshy prehensile trunk that it uses to grab leaves, breathe, and even snorkel. Its two-tone coloration is distinctive among tapir species, with a black body and white “saddle” that extends all the way around its belly and rump.

Asian tapirs are Endangered largely due to habitat loss. Oil palm plantations and illegal logging are taking away their forests in both Malaysia and Sumatra. They often get caught in snares set for other animals, and while not historically hunted for their meat, that may change as preferred food species are depleted.

Wild yak: Like the American bison, Wild yak (Bos mutus) once roamed widely, moving across much of Asia. Today, however, they’re limited to the high-elevation Tibetan-Qinghai Plateau.

Little is known about the species, but a recent study counted 990 wild yaks in China’s Hoh Xil Nature Reserve. Overhunting and competition with livestock have depleted populations, but a more significant threat now is climate change and the impact it is having on the high-altitude glaciers and alpine meadows it calls home.

Saola: Known as the Asian unicorn for its rarity and long pointed horns, the critically endangered Saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) — pronounced sow-la — is yet another species that may disappear before much of anything is known about it.

The name Saola translates from the Tai language of Vietnam as “weaving needles”, a likely reference to the animal’s sharp horns. The species lives only in the rugged and little explored wet evergreen forests of the Annamite Mountain range in north-central Vietnam and Laos — a biologically rich region, with many other species ranging from tigers to Asian elephants, and Douc langurs.

The Saola was unknown to science until 1992, when its smooth spindle-shaped horns were discovered in the house of a local hunter. Not much more has been learned since then, but villagers say they’re solitary diurnal creatures who graze on the leaves of fig trees and bushes, along with grasses.

There have been no population studies, but some conservationists believe that about 200 still live in Vietnam. Scientists have only documented them in the wild a handful of times. According to the IUCN Red List, “the paucity of data on Saola is itself an indication of its critically small population.”

The greatest threats to Saola survival are both subsistence and incidental hunting, from snares set for other species, and forest clearing for timber or to make room for agriculture, roads or hydropower projects. Vietnam lost nearly 1.2 million hectares (4,630 square miles) of forest from 2001 to 2012 according to Global Forest Watch.

Yangtze Finless porpoise: The long list of under-the-radar species slips under the water, too. The Yangtze Finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) is a freshwater mammal dubbed the “underwater panda” because of its “smile” and “cute demeanor”. Unfortunately, these anthropomorphic qualities haven’t helped the species much. It is in dire straits, largely due to the degradation of China’s Yangtze River, one of the world’s most developed rivers.

Heavy boat traffic, pollution and dams have drastically altered the river’s ecology and cut the finless porpoises off from their food and breeding sites. Their numbers have dropped precipitously — halved from 2,000 in 2006, to 1,000 in 2012 — and conservationists fear they may go the way of their close cousins, the Baiji or Yangtze river dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer), now functionally extinct. China recently relocated eight Finless porpoises to new habitats to stave off that fate.

Asia’s forgotten reptiles, amphibians, birds and fish

Red-crowned Roof turtle: The Critically Endangered Red-Crowned or Bengal Roof turtle (Batagur kachuga) is native to India, Bangladesh and Nepal, but has disappeared over much of its range with the last known strongholds of this freshwater turtle on the Chambal River in central India.

Hunting and habitat degradation have devastated the species. Dams, pollution, agriculture and sand mining at nesting sites have taken a heavy toll, as did domestic consumption of eggs and accidental drowning in fishing nets. Contributing to the demise is the fact that the animals make relatively easy targets due to their predictable nesting habits and loyalty to repeated use of specific sites. It is thought that there are less than 400 adult females in the wild.

A Turtle Survival Alliance program in India’s National Chambal River Sanctuary is relocating eggs, protecting sites from predation, and returning the hatchlings to the river. Results have been positive, with the 115 Red-Crowned Roof turtle nests it protected in 2016 yielding over 1,800 hatchlings. So there is still hope for this Almost Famous species.

Limnonectes larvaepartus (an Indonesian fanged frog): Limnonectes Larvaepartus is a newly described fanged frog endemic to Indonesia’s Sulawesi island. It is unique because it is the only frog to give birth to tadpoles.

Roughly a dozen other frog species reproduce with internal fertilization, but they differ in that they lay fertilized eggs or give birth to tiny froglets. For the rest of the world’s 6,455 frog species, fertilization happens externally, with the male releasing its sperm as, or after, the female releases her eggs.

Described by scientists in a December 2014 paper published in PLOS One, L. Larvaepartus is a gray or brown frog that is less than 2-inches long. It joins the group of other Sulawesi fanged frogs, so named because of the fang-like projections on their lower jaw. Little is known about most of these species, as only a handful of what scientists think may include as many as 25 species have been formally described.

L. Larvaepartus is an example of the challenges faced by Asia’s frogs, which are being wiped out as rapidly as they are discovered. With many species still unstudied, the rapid one-two punch of climate change, habitat destruction, pollution, disease and hunting make these amphibians particularly susceptible to extinction.

Gurney’s Pitta: This endangered passerine or perching bird is one of the most sought after by bird watchers in Southeast Asia, likely due to its rarity and striking coloration. It boasts an iridescent blue cap and tail, with underparts painted black-and-yellow. It was thought to be extinct until 1986 when several pairs were spotted in Thailand. Today, a small number of individuals live in Thailand’s Khao Pra Bang Kram Wildlife Sanctuary, and roughly 15,000-26,000 were found in Myanmar, according to BirdLife International.

The future prospects for Gurney’s Pittas remains bleak. They live in flat, low-lying forest, which happens to be the same areas that are perfect for the development of oil palm, rubber and coffee plantations. Further, forest loss is a constant threat. While the Thai population is located in a protected area, Myanmar’s larger population is in an unprotected one. That may spell doom for these birds unless a national park is established there, which is a possibility.

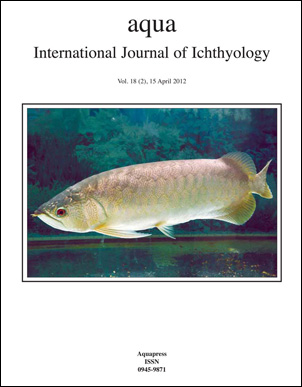

Asian Arowana fish: Asian arowanas (Scleropages formosus) have been called “the world’s most coveted fish”. They are so highly sought after for the aquarium trade that they have been classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List and also listed under Appendix I of CITES, which prohibits their commercial trade.

Those classifications have spawned both captive breeding, which is allowed, and a thriving black market, which was recently described in a new book by Emily Voigt, titled Dragon Behind the Glass: A True Story of Power, Obsession and the World’s Most Coveted Fish. In it, she tells how a single adult Asian arowana, also known as a dragon fish or bonytongues, commanded $150,000 on the black market.

Found throughout Southeast Asia — from Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam to Indonesia and Peninsular Malaysia — these fish grow to about three feet in length and are valued for their green, golden and red color variations.

Knowledge is power, and love may be the answer

More than 16,000 species around the globe have been placed on the IUCN Red List, and are threatened with extinction — that’s one in three amphibians, one in four mammals, and one in eight birds.

New species are being discovered all the time, even as others vanish forever from the planet. Still more species await discovery, or may disappear completely before we even notice they’re around.

While much focus has been placed on the plight of charismatic megafuana or ecological keystone species, many thousands of animals remain at risk. But they attract little or no attention from media, conservation groups or governments.

More research is urgently needed to not only identify these Almost Famous species, but also to learn about their place in nature, their importance to their ecosystems and to humanity. Out of that knowledge may grow the desire and drive to act.

As Australian conservationist Steve Irwin put it succinctly: “If we can teach people about wildlife, they will be touched.… Humans want to save things that they love.”