|

Perspectives on proposed changes to Brazil’s Forest Code

|

A recent push to revise Brazil’s forest code has emerged as one of the more contentious political issues in the country, pitting agribuisness against environmentalists trying to preserve the Amazon rainforest. Historically, the forest code has required private landowners to maintain a substantial proportion of natural forest cover on their properties, though the law has often been ignored.

Now, a powerful “ruralista” bloc, consisting of large farmers and ranchers, argues that the forest code needs to be relaxed in order for Brazil to continue its breakneck growth as an agroindustrial superpower. These ruralistas contend that because the forest code has been so widely flouted—more than 90 percent of landowners in the Amazon are operating illegally—a large component of the Brazilian economy is effectively “illegal”, undermining governance and efforts to improve land management.

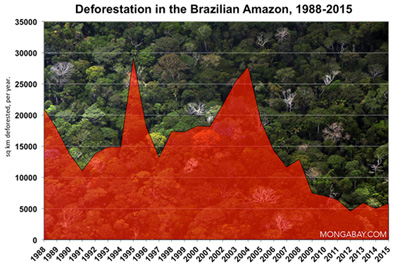

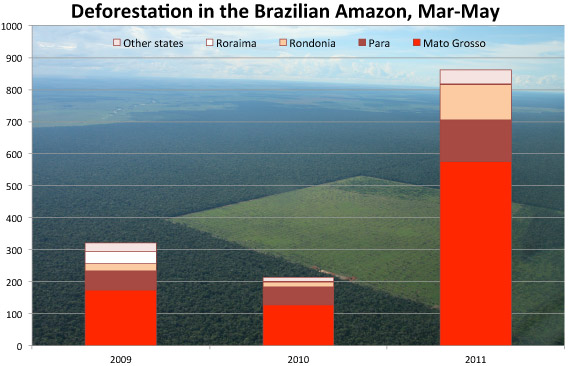

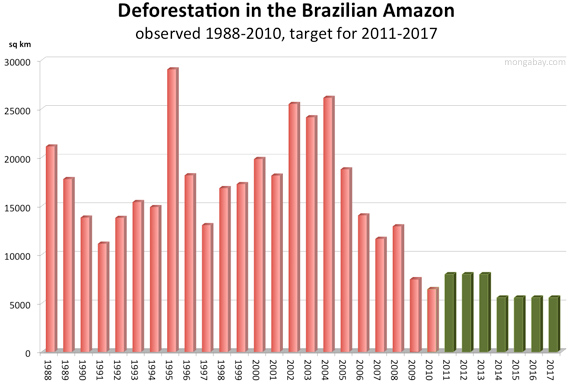

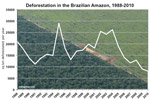

But environmentalists say the proposed changes—including reducing forest cover requirements and granting amnesty for past deforestation of areas up to 400 ha—could undermine recent progress on reducing deforestation and hurt Brazil’s international climate commitments. Already, the media has linked a recent rise in Amazon destruction to landowners’ expectation of eventual amnesty.

Antonio Donato Nobre |

While both sides claim to be basing their recommendations on the “best science” available, Brazilian scientists say they haven’t had much of a voice in the debate. In fact, says Antonio Donato Nobre, a researcher at the Amazon Research Institute and Brazil’s National Space Research Institute, “throughout the development of the said revisions, Congress has neither invited nor commissioned a coordinated and serious contribution from the scientific community.”

Nobre says lack of consideration of science in the forest code debate could prove perilous to Brazilian agriculture, which is heavily dependent on services generated by the vast Amazon rainforest. Should the new forest code sanction large-scale deforestation, as some fear it might, Brazil’s farmers and ranchers could undermine the very ecological system that sustains their industry.

“The scientific analysis supports the notion that active conservation of natural areas within farms makes complete agronomic, economic and ecological sense,” Nobre told mongabay.com.

Nobre adds that a scientific approach to reforming the forest code could offer a way forward on improving the long-term sustainability of Brazil’s economic growth.

“With proper application of modern technological tools, the new forest code could become a source of stimulus for increased, responsible and sustainable agricultural output, while at the same time allowing for the ecological and economic rehabilitation of large areas of degraded lands all around Brazil,” he said. “It will be completely inexcusable if all of that illuminating and liberating knowledge and technology is put aside by an old-fashioned political and ideological dispute.”

In the first part of a two-part August 2011 interview with mongabay.com, Nobre talked about the need to integrate scientific analysis into any revision of Brazil’s forest code.

This interview is also available in Portuguese

AN INTERVIEW WITH ANTONIO DONATO NOBRE

mongabay.com: What is your background and what led you to pursue your area of work?

Antonio Donato Nobre |

Antonio Nobre: I am an agronomist by training. I worked with research in soils and agriculture for 12 years early in my career. However, as I realized that conventional agriculture treated the complex environmental support system it relies on as an expendable resource, I felt the urge to veer more and more into fundamental sciences. I first deepened my knowledge in tropical biology (MSc); then I broadened to Earth Sciences (PhD); and lately I’ve been dealing with computational modeling of terrains on the landscape, a subject that brought me close to the forest code debate.

mongabay.com: You and other Brazilian scientists have been following the forest code debate closely. What are your thoughts on the proposed revisions? How will proposed changes impact the Amazon?

Antonio Nobre: The ongoing political revision of the forest code has a few merits and many defects.

In a country with more than 80 percent living in cities, the hearings for the forest bill created a stage where farmers aired their aspirations and difficulties with the law. They criticized the forest code on accounts of inapplicability and exaggerated restrictions on how private properties should allocate land uses. Because the forest code is regarded as rigorous, often times this has been used by farmers as excuse for not complying with the law. Curiously, the same rigor deemed excessive by farmers is used as deflector shield against international criticism on deforestation. In reality, over time the Brazilian forest law hasn’t been very effective in stopping deforestation, perhaps just because it was little respected and little enforced.

But this situation began to change. Environmental degradation in Brazil is nothing new, but in recent decades the wholesale destruction of biodiversity-rich natural ecosystems has peaked to alarming rates. Worsening the perception of loss, Brazil has been struck by a string of bad catastrophes, like floods and landslides. This combination triggered strong social outcry and demands for action against forest destruction.

Antonio Donato Nobre |

Curbing of deforestation came in various forms like banks cutting the money-line to offending farms; law enforcement imposing heavy fines; public prosecutors suing forest code offenders criminally; and consumers rejecting agricultural products derived from deforested areas. All of these actions exposed the age-old problem of disregard for the law, as it became clear that a large proportion of farmers had not complied with obligatory protection areas inside their properties. To complicate matters, it has become really difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff, as not all farmers are guilty of wrongdoing. Some farms on areas of old colonization had areas deforested even before the first law came into effect, in 1934. The mounting pressure had the net effect of worsening the fight between landowners’ organizations and environmental movements. As the former attempts to change the forest law in their favor, granting amnesty for past environmental offenses, the latter held position attempting to bullet-proof the standing law and keeping momentum for the hard-fought restrictions on deforestation.

In summary, action for rural development (read expansion of agricultural areas over natural ecosystems) prompted reaction from government and environmental groups (read strengthening environmental laws), which prompted the current backlash onto the law itself. Even before it passed in the House of Representatives, the proposed amnesty to deforesters, or the prize of impunity as it is called in Brazil, has already caused concern. It has been suggested that the forgiveness for offenders built in the new bill is the cause of recent worsening in deforestation as well as the increased criminal violence in the countryside. If just a promise of amnesty can unleash a surge in deforestation and violence, what destructive effects will the lax new forest bill have if it becomes law?

mongabay.com: Senator Katia Abreu has campaigned in the last year saying that science would save the forest code. Do you as a scientist believe that scientific research has been properly incorporated into the planned revision of the forest code?

Science can help solve the forest code puzzle |

Antonio Nobre: Throughout the development of the said revisions, Congress has neither invited nor commissioned a coordinated and serious contribution from the scientific community. Nevertheless, on their own initiative, the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science and the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, the two most reputable and representative scientific organizations in Brazil, have assembled a working group and sponsored a deep scientific analysis of the forest code, both for the standing law as well as for the proposed alterations of the law, now under the scrutiny of the Brazilian Senate. The working group was composed of respected Brazilian scientists, with about half coming from EMBRAPA, the agricultural research powerhouse at the root of the Brazilian agricultural success. This working group was not paid to produce the study; the scientific associations that sponsored the group had neither connections to environmental NGOs nor to organizations of farmers. The group strove to remain independent and every member pledged to maintain strict scientific objectivity. Last April a book with the findings of the analysis (Portuguese version, FAQ) was presented to Brazilian society, to Congress and to several ministers of the federal government. The book—written over the course of 10 months—consulted more than 300 relevant scientific papers and cited 170, so a significant portion of the most recent and solid science available was critically reviewed and presented.

mongabay.com: Are recommendations from scientists being considered by Congress as it weights the forest code revisions?

Antonio Nobre: The new forest law is being pushed politically through Congress, in spite of widely recognized absence of science and even of a few demonstrated violations of the scientific rational. Given that both earlier versions of the forest law, from 1934 and 1965, were built on top of the best science available at those times, omitting science in 2011 becomes quite an unexplainable situation. The most ironic thing is that Brazil sells an image of scientific and technological competence breeding the success of its agribusiness. A public opinion poll taken several weeks ago found that 77 percent support the participation of scientists in the development of a new forest code. Yet, in spite of manifest interest of several senators, the Senate has as of the end of July forgone the indication of its Science and Technology commission, after having appointed three other commissions to revise the bill (agriculture, environment and constitution & justice).

|

Recently, more than 8,000 members of the scientific community, assembled in their annual congress, sent strong motions to the Senate stating that science should be considered in the revision of the bill. The upcoming weeks will tell whether our legislators will listen to the call of science.

Supposing that the senators will open a serious space for enlightened debate, there are still a few dangers lurking ahead. Even if Senate improves the bill, as it might, the bill will have to be approved again by the House of Representatives, where it was first crafted, and where it can just go straight back to its original form. The last line of defense is a potential veto by the President, which can nonetheless, be overruled by Congress. If that happens, only the Supreme Court can intervene, as the present text of the bill, according to a few of the best experts in law, seriously violates a number of constitutional precepts. Clinging to the text as it is now ensures a stormy judicial path ahead, and will also keep public opinion massively against agribusiness. Farmers in general do not deserve the bad name the troubled change of the forest code is giving them.

mongabay.com: Is there an opportunity for reconciliation between the farm lobby and environmentalists? Can Brazil boost productivity on degraded lands such that it can meet output targets without clearing substantially more forest?

Antonio Nobre: The drama in this clash is that the scientific reality shows no need for conflict. The working group found, based on hundreds of studies, that there is a significant synergy still waiting to be explored between agricultural production and environmental conservation within private properties. A powerful example comes from Georgia in the United States, where landowners and agribusiness teamed up with environmental NGOs to estimate the economic value of environmental services provided to urban areas by remnants of natural forests within private farms. Their figure, US$ 37 billions per year, accounts only for well-established metrics of exported environmental services, like cleaning water and prevention of silt in streams. If urban consumers would pay part of their water bill to farmers, so to compensate for the environmental services received, that would be a win-win situation. The expense of clean water flowing from a well-established forested catchment has been demonstrated to be one hundredth of that to clean pollutants and sediments from a contaminated source. So, paying farmers for these services would be much more economic and healthy than converting sewage into potable water. The working group study found many pluses like clean water from conservation of forests on private lands. In the direct interest of farmers there are many examples of forests generating beneficial services including boosting wild pollinators and natural predators of agricultural pests. Protection forests are therefore not obtrusive to production, rather the opposite; they contribute to yields and reduce the need for costly agrochemicals. The study also found that the forest code did not protect excessive areas within properties and that Brazil has huge areas for agricultural expansion if available technologies for higher yields are applied and degraded lands are recovered. It is completely viable to increase agricultural production many-fold while maintaining natural ecosystems and even recovering degraded forests within properties. All in all, the scientific analysis supports the notion that active conservation of natural areas within farms makes complete agronomic, economic and ecological sense.

But the good news from science did not stop there. As an unforeseen spinoff in the scientific revision of the forest code, the Working Group found that the old law could benefit from a technological upgrade. In 1965 there were no Earth resource satellites sending reams of remotely observed surface data as we have today; back then the most powerful computer had a fraction of the capacity we find in any cellular phone today. New virtual models of the landscape, built from radar or laser 3D image data, have been demonstrated as powerful tools in the indication of the best and most productive soils for agriculture, as well as in revealing where there is terrain more suited for conservation and production of environmental services. Such technologies if adopted will allow for the emergence of a new era of intelligent and organic use of the landscape. Therefore, neither the forest code, with its fixed geometric prescriptions for buffer zones, nor the new forest bill, which is being born old and poor of science, are the solutions for an era where resource optimization is becoming crucial. Besides the obvious treasure of biodiversity, what is at stake is the continued and sustainable success of the Brazilian prowess in agriculture, converting its historical culture of waste of natural resources into savvy application of innovation and technology in gaining sustainability.

Based on such abundant evidence of brilliant solutions at hand, which can extinguish the false dilemma between agriculture and conservation, the Brazilian scientific community is legitimately seeking to play the role of an independent and objective third party on the matter. There is a wide logical road ahead that could solve the conflict and, better yet, create new sustainable wealth. The scientific facts are very clear, with proper application of modern technological tools, the new forest code could become a source of stimulus for increased, responsible and sustainable agricultural output, while at the same time allowing for the ecological and economic rehabilitation of large areas of degraded lands all around Brazil. It will be completely inexcusable if all of that illuminating and liberating knowledge and technology is put aside by an old-fashioned political and ideological dispute.

Reference:

Related articles

Proposed changes to Brazil’s Forest Code could hurt economy

(07/13/2011) Proposed changes to Brazil’s Forest Code will hurt Brazilian agriculture, argues a leading conservationist. Carlos Alberto de Mattos Scaramuzza, WWF-Brazil’s director for conservation, says the reform bill currently being evaluated by Brazil’s Senate could have unexpected economic implications for Brazilian ranchers and farmers. Scaramuzza says a bill that grant amnesty for illegal deforesters and sanctions expanded destruction of the Amazon rainforest would make Brazilian agricultural products less attractive in foreign markets.

Prominent scientists condemn proposed changes to Brazil’s Forest Code

(07/07/2011) A group of prominent scientists has condemned a bill that will potentially weaken Brazil’s environmental laws.

Forest Code bill could undermine sustainable growth in the Amazon

(07/06/2011) In May Brazil’s House of Representatives passed a bill that will reform the country’s Forest Code, which requires farmers and ranchers in the Amazon to maintain a legal forest reserve amounting to 80 percent of total landholdings. Environmentalists say the bill, which is undergoing revision before heading to the Senate next month, would weaken the forest code, granting amnesty for illegal deforestation of up to 400 hectares per property and allowing clearing of forests along waterways and on hillsides — restrictions meant to limit erosion and damage to watersheds.

Brazilian senator: Forest Code reform necessary to grow farm sector

(07/06/2011) Over the past twenty years Brazil has emerged as an agricultural superpower: today it is the largest exporter beef, sugar, coffee, and orange juice, and the second largest producer of soybeans. While much of this growth has been fueled by a sharp increase in productivity resulting from improved breeding stock and technological innovation, Brazil has benefited from large expanses of available land in the Amazon and the cerrado, a grassland ecosystem. But agricultural growth in Brazil has always been limited — at least on paper — by its environmental laws. Under the country’s Forest Code, landowners in the Amazon must keep 80 percent of their land forested.

Brazilian government: Amazon deforestation rising

(06/30/2011) Satellite data released today by the Brazilian government confirmed a rise in Amazon deforestation over this time last year.

Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon continues to rise; clearing highest near Belo Monte dam site

(06/17/2011) Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon continued to rise as Brazil’s Congress weighed a bill that would weaken the country’s Forest Code, according to new analysis by Imazon.

Bloody June: fifth rural activist assassinated in Brazil this month

(06/16/2011) A rural worker who confronted illegal loggers operating in the Brazilian state of Pará was found murdered near his home, reports the Associated Press. Murdered on the Esperanca landless settlement, his death is likely related to ongoing conflicts between loggers and farmers in the Esperanca community. The victim, Obede Souza, is the fifth person to be murdered this month after standing up to illegal loggers.

Revised Forest Code may cost Brazil climate commitments

(06/14/2011) The proposed revision of Brazil’s Forest Code could prevent the country from meeting its lower emissions target and is unlikely to ease rural poverty, concludes a new study by the Brazil-based Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA).

Majority of Brazilians reject changes in Amazon Forest Code

(06/11/2011) The vast majority of Brazilians reject a bill that would weaken Brazil’s Forest Code, according to a new poll commissioned by green groups.

Monitoring deforestation: an interview with Gilberto Camara, head of Brazil’s space agency INPE

(02/08/2011) Perhaps unsurprisingly, the world’s best deforestation tracking system is found in the country with the most rainforest: Brazil. Following international outcry over immense forest loss in the 1980s, Brazil in the 1990s set in motion a plan to develop a satellite-based system for tracking changes in forest cover. In 2003 Brazil made the system available to the world via its web site, providing transparency on an issue that was until then seen as a badge of shame by some. Since then Brazil has become recognized as the standard-bearer for deforestation tracking and reporting—no other country offers the kind of data Brazil provides. Space engineer Gilberto Camara has overseen much of INPE’s earth sensing work and during his watch, INPE has released several new exciting capabilities.