Study confirms links between deforestation and local elections in Indonesia. Politicians in forest districts appear to often rely on funding from loggers, plantation developers, and miners to fund their campaigns.

Increased fragmentation of political jurisdictions and the election cycle contribute to Indonesia’s high deforestation rate according to analysis published by researchers at the London School of Economics (LSE), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and South Dakota State University (SDSU).

The research confirms the observation that Indonesian politicians in forest-rich districts seem repay their election debts by granting forest concessions.

Comparing changes in forest cover in different ‘forest zones’ with the proliferation of new administrative regions across Indonesia — a product of decentralization, which grants greater regional autonomy — authors led by Robin Burgess of LSE found that subdividing a province by adding a district increases the incidence of deforestation within that province by 7.8 percent. The number of districts across Indonesia leapt from 291 to 498 between 1998 and 2009.

Deforestation in Indonesian Borneo |

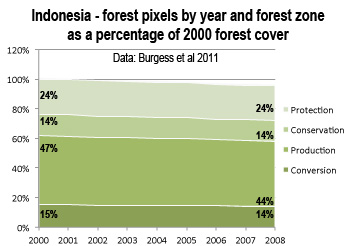

The increase in political units is important because it means there are more elections. The researchers found that illegal logging — forest felling in ‘conservation’ and ‘protection’ zones where no logging is allowed — increases during the run-up to local elections, but falls sharply in the year after the election, replaced by a steep increase in logging in ‘conversion’ zones. The shift from illegal to legal logging may be a consequence of politicians’ paying back favors — in the form of logging concessions — to interests that sponsor their campaigns.

“We document a ‘political logging cycle’ where local governments become more permissive vis a vis logging in the years leading up to elections,” the authors wrote. “We find that deforestation in zones where all logging is illegal increases by as much as 42 percent in the year prior to an election…. Illegal logging then falls dramatically (by 36%) in the election year and does not resume thereafter.”

“In the conversion zone, we find a 40% increase in logging in the year of the election and a 57% increase in the year following the election.”

Indonesia – forest pixels by year and forest zone as a percentage of 2000 forest cover. Data: Burgess et al 2011. |

Owing to a relatively small middle class and other factors, local elections in Indonesia are often funded by people and companies associated with extractive industries like logging, mining, and plantation development. This is important because the bupati, or district head, holds a lot of power when it comes to decisions on what land will be used for agriculture and plantations, and whether illegal logging will be tolerated.

The results are significant for Indonesia’s effort to slow deforestation under its billion dollar partnership with Norway and the broader Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) initiative. Namely, the paper suggests that election reform is needed to address deforestation.

“To the extent one wants to slow the rate of tropical deforestation, these results matter. They suggest that unless the incentives of local politicians and bureaucrats are taken centrally into account then central or donor driven policies to counter deforestation may be ineffective,” the authors write.

“Unless REDD programs are designed taking into account those local actors who currently derive considerable benefits from legal and illegal logging, it is unlikely to be

effective.”

CITATION: Robin Burgess, Matthew Hansen, Benjamin Olken, Peter Potapov, and Stefanie Sieber. The Political Economy of Deforestation in the Tropics. London School of Economics. January 2011

Related articles

New World Growth report contains ‘false and misleading’ information

(03/31/2011) A new report from World Growth International, a lobby group for industrial forestry interests, contains ‘false and misleading’ information on the economic impact of reducing Indonesia’s deforestation rate, says an Indonesian environmental group. The report, released today, claims that reducing deforestation in Indonesia will cost the country 3.5 million jobs annually by slowing expansion in the forestry sector.

Will Indonesia’s big REDD rainforest deal work?

(12/28/2010) Flying in a plane over the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea, rainforest stretches like a sea of green, broken only by rugged mountain ranges and winding rivers. The broccoli-like canopy shows little sign of human influence. But as you near Jayapura, the provincial capital of Papua, the tree cover becomes patchier—a sign of logging—and red scars from mining appear before giving way to the monotonous dark green of oil palm plantations and finally grasslands and urban areas. The scene is not unique to Indonesian New Guinea; it has been repeated across the world’s largest archipelago for decades, partly a consequence of agricultural expansion by small farmers, but increasingly a product of extractive industries, especially the logging, plantation, and mining sectors. Papua, in fact, is Indonesia’s last frontier and therefore represents two diverging options for the country’s development path: continued deforestation and degradation of forests under a business-as-usual approach or a shift toward a fundamentally different and unproven model based on greater transparency and careful stewardship of its forest resources.