Peru’s environment minister now says the government will pay indigenous communities 10 sols ($3.30) for every hectare of rainforest they help to preserve, reports the Latin American Herald. Previously Antonio Brack said that communities would see about half that amount.

The $3.30-per-hectare figure is low by international standards. Under a proposed mechanism that compensates countries for reducing deforestation (REDD), forest land could be worth $800 or more per hectare for its carbon (225 tons of carbon/ha), depending on its level of threat. Forests in areas of high deforestation would be compensated at a higher rate than inaccessible forests at low-risk of development.

But Brack left open the possibility that communities could receive higher payment if parties agree to include REDD compensation in a future climate framework.

Strangler fig in the Peruvian Amazon. Image by Rhett A. Butler |

“If the idea is approved internationally at the coming 15th Climate Change Summit in Copenhagen, it could obtain international support for conservation and we could as much as double that payment,” Brack was quoted as saying by Spanish news agency EFE.

The initiative could generate nearly $37 million for indigenous communities which control 11 million hectares of forest in the country. Presently indigenous communities are said to receive $30,000 per year in direct international support for forest conservation.

The announcement comes less three months after Japan agreed to loan Peru $120 million to protect 55 million hectares (212,000 square miles) of Amazon rainforest over the next ten years. Germany has also pledged 5 million euros ($7 million) to forest conservation in the country. The measure is expected to avoid emissions of 20 billion tons of carbon dioxide, or more than 60 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2005.

“One of the worst problems about global warming is that mankind in the last 500 years has destroyed 50 percent of forests on the planet and that is a very serious problem indeed,” Brack was quoted as saying.

“Up to now development has consisted of the woodland practice of slash and burn to clear land for crops and livestock, but that has given mediocre results because of the 10 million hectares (39,000 square miles) where that has been done, 8 million hectares (31,000 acres) are unproductive. It’s shameful and we can’t keep doing it.” he said, adding that programs aims “to save these forests and at the same time see how we can give a basic income to these communities for the woodland they preserve.”

Peru. Photos by Rhett A. Butler |

“Peru can contribute enormously to the world in preserving biodiversity, native cultures and forest management, and we’re laying down a big challenge to protect those forests, create wealth from them and not destroy them.”

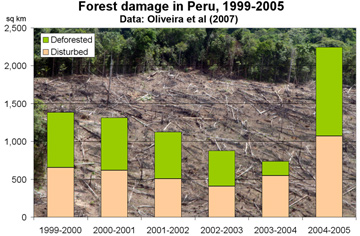

Peru — home to the fourth largest extent of tropical rainforests after Brazil, Congo, and Indonesia — has historically had one of the lowest annual deforestation rates in the Amazon basin, but forest loss has been increasing in recent years due to illegal logging, mining, agriculture, and expansion of road networks, including the paving of a highway that provides access to a remote and biologically-rich region in southeastern part of the country. In 2005 — the most recent year for which data is available — at least 150,000 hectares of forest was lost, while a similar area was degraded through logging and other activities.

Conflict between developers and native communities has been escalating over the past year. In June more than 30 were killed in a clash between indigenous protesters and federal police over the government’s plan to promote energy development in the Amazon rainforest. More than 70 percent of the Peruvian Amazon is now under foreign concession.

Deforestation rates in Peru, 1999-2005. Image by Rhett A. Butler |

Deforestation and land use change accounts for roughly 70 percent of Peru’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC). Spanning a variety of ecosystems, including the dry coastal region, the tropical Amazon, and the high Andes, the country is particularly vulnerable to climate change. The Peruvian government estimates that the country’s glaciers have shrunk by more than 20% in the past 30 years and expects them all to disappear by 2040. The loss of glaciers, which are the source for as much as 50 percent of the water in the upper Amazon, could have a significant impact on agriculture and urban water supplies as well as the Amazon rainforest. Indigenous communities are believed to be especially at risk from climate shifts.