This is the third part of a four-part series examining trends in Protected Area Downgrading, Downsizing, and Degazettement (PADDD). Read the first and second parts for a more comprehensive look at the issue.

Brazil is the country with the largest protected area system in the world, spanning nearly 220 million hectares of land, from the Pantanal marshes to rainforest crawling with wildlife. The country is home to endangered species such as the golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) and the brazil-nut poison frog (Adelphobates castaneoticus) that cannot be found anywhere else on the planet.

Its protected areas (PAs) include over half the Amazon rainforest, and make up a total of 12.4 percent of all PAs the world over. According to Global Forest Watch, an environmental data repository run by the World Resources Institute that tracks global forest change, 58 percent of the country is forested.

It is no wonder then that Brazil and its rainforests are referred to as the “lungs of the world” – but can they breathe on our behalf forever?

Golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) are endemic to Brazil’s Atlantic forests and highly endangered. Image by Magnus Mansk.

Home to 198.6 million people spread over 8.5 million square kilometers (3.2 million square miles), Brazil has reserved about 17.6 percent of its land (1.5 million square kilometers) to receive protection from unauthorized exploitation of resources. These include 886 federal, 729 state, and 147 municipal conservation units (CUs) – a remarkable achievement for one country.

Recent analyses of Protected Area Downgrading, Downsizing and Degazettement (PADDD) by Enrico Bernard from the Department of Zoology of the Federal University of Pernambuco in Brazil, published in the journal Conservation Biology in early January, reveal however, that the “lungs of the world” might have some difficulty breathing for us in the future.

Pasture abuts legal forest reserve in the Brazilian Amazon. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Despite significant expansions in protected areas since the mid-2000s, PA formation has stagnated in Brazil since 2009.

“We identified 93 events that changed the boundaries or categories of Brazilian CUs in the last 31 years: 5 downgrading, 26 downsizing, 11 degazetting, 49 reclassifying, and 2 upgrading,” note Bernard and colleagues in their article.

Degazettement is defined as the complete revoking of protected area status, effectively removing all security a piece of land may enjoy from being exploited. According to Bernard, of all of these PADDD events, 42.3 percent occur in the Amazon Basin, affecting an area slightly larger than the state of West Virginia. While most of the affected area falls under the category of downsizing and downgrading, 17 percent was legally degazetted.

In Brazil, none of this degazettement occurred in federally sanctioned CUs. However, nearly half (42.6 percent) of all PADDD events within state CUs involved degazettement. More disturbingly, degazettement actually affected 70.7 percent of areas undergoing PADDD within state CUs.

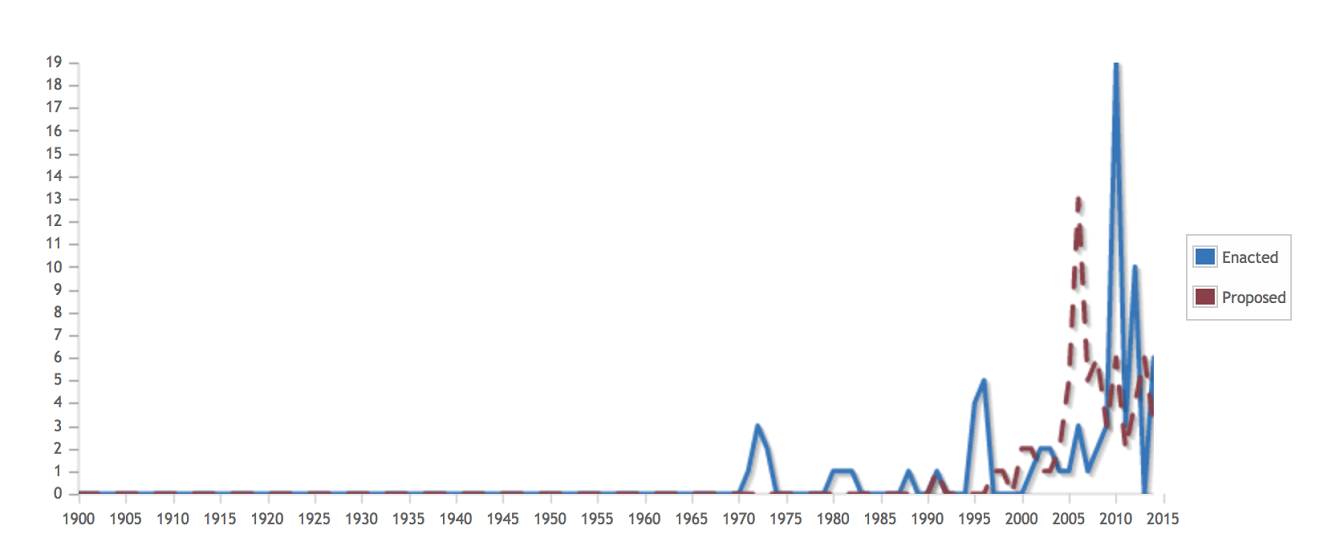

PADDD events in Brazil have a discernible trend – one that can only be described as increasing at an exponential rate. While Bernard detected only six events from 1981 to 2000, there were 37 in 2011 alone – in fact, 74.1 percent of all PADDD experienced in the country occurred only between 2008 and 2012.

A world map indicating all degazetting events documented by the WWF’s PADDDtracker. Brazil alone has a high concentration of these events globally. Click to enlarge.

PADDD events over time in Brazil, depicting recent drastic increases in both proposed and enacted events. Data from PADDDtracker.org. Click to enlarge.

Proposed PADDD events

At the start of 2014, there were four legislative bills that proposed to degazette, downsize, or downgrade five CUs in the Brazilian Amazon. All but one were in the northeastern state of Pará, a state with 83 percent forest cover, according to Global Forest Watch.

“Two bills were proposed in the Chamber of Deputies and two in the Federal Senate from 2006 to 2009,” reports Bernard in his analysis. All of these bills have received at least one favorable vote, which indicates they will remain in the pipeline for plenary votes in the future.

“If the bills are enacted,” Bernard writes, “the changes would affect parks and reserves that cover 2,102,951 hectares.” In other words, more than 8,000 square miles (20,000 square kilometers) of forest could be impacted by this legislation.

The Degazettement of Pará

In the often-conflicted state of Pará, on the morning of February 12, 2005, Sister Dorothy “Dot” Mae Stang stepped out of her home to walk to a community meeting. Originally from Ohio, Sister Stang was a forceful advocate for the rural poor and their rights in the face of larger organized ranchers.

That morning, even the bible she habitually carried with her did not prevent two armed men from remorselessly gunning her down. Given her service to underrepresented people in Brazil as an environmental activist, the United States Government and Brazil coordinated the arrest of her killers, who were subsequently sentenced to several decades in prison.

The area in which she was murdered falls near highway BR-163 in Pará. After first declaring a logging moratorium in the area, President H.E. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil subsequently went on to announce a significant expansion in land protection in the area, particularly near the highway. The February 2006 decree brought the total protected area in that region of Pará to 6.4 million hectares, which is more than twice the size of Belgium.

This move in 2006, lauded as a remarkable achievement by the conservation community, also experienced almost immediate opposition from Brazilian politicians. The decree that created these protected areas – Jamanxim National Forest and National Park, Rio Novo National Park, Tapajós Environmental Protection Area, Crepori National Forest, Trirão National Forest and Amana National Forest – is being challenged in court today.

Area of proposed degazettements in Brazil, highlighting Pará, where a large expansion in protected areas is now being threatened in court. Data from PADDDtracker.org. Click to enlarge.

Congressman Asdrubal Bentes proposed to overturn the Presidential decree in May 2006, just three months after its issuance, citing that the protected areas, intended by Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva to ensure that planned paving of highway BR-163 does not result in increase logging in adjacent forests, were created illegally. Bentes claimed the president overstepped the limits of executive power and expropriated land without consulting the Congress or the State Government of Pará.

Thus, even the future of this remarkable expansion is now questionable – and an area of over 62,960 square kilometers runs the risk of degazettement.

The Brazilian state of Pará, showing tropical carbon forest stocks overlaid with tree cover loss. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge. |

The importance of Brazil’s Conservation Units

According to Bernard and colleagues, Brazil’s trend in downsizing or degazettement of its PAs may have dire consequences when it comes to carbon emissions—and, thus, climate change.

“Their creation and maintenance sequesters at least 2.8 billion tons of carbon, conservatively estimated to have a value of US$48.3 billion,” the authors write. The carbon stock alone held by these areas alone is valued at $1.46 billion to $2.92 billion each year. In addition, more than two million tourists visit these conservation units in Brazil annually, which has an economic impact of nearly $1.10 billion.

The ultimate message of these studies is crystal clear: protected areas afford ecosystems services and economic benefits in a world with a shaky future – fulfilling the critical need to stem extinction and deforestation rates, and mitigate climate change.

As Bernard puts it, “the weakening of such networks due to PADDD events, such as those happening in Brazil and other parts of the world, compromises the capacity of these areas to deliver benefits that may be crucial in a near future.”

Citations:

- Bernard, E., LAO PENNA, and E. Araújo. “Downgrading, Downsizing, Degazettement, and Reclassification of Protected Areas in Brazil.” Conservation Biology (2014).

Mascia, Michael B., and Sharon Pailler. “Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD) and its conservation implications.” Conservation Letters 4.1 (2011): 9-20.- World Wildlife Fund. 2014. PADDDtracker.org Data Release Version 1.0 (January 2014). Washington, DC: World Wildlife Fund.

}}

Related articles

Local communities rise to the forefront of global conservation practice (commentary)

(10/29/2014) A few weeks ago, a remote aboriginal community in western Australia made headlines when it completed the establishment of an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) containing over 4.2 million hectares of desert and grassland. The Kiwirrkurra IPA, as the area is known, is billed as the largest protected expanse of arid land on Earth.

(10/29/2014) In India’s central state of Madhya Pradesh lie 500 square kilometers (200 square miles) of protected land demarcated as the Panna Tiger Reserve. Recently, however, its protection status has been questioned, and global-scale analyses show Panna is far from alone among India’s many threatened Protected Areas.

World’s rarest gorilla gets a new protected home

(10/28/2014) The Cross River Gorilla, the rarest and most threatened of gorilla subspecies, has reason to cheer. Last month, on September 29, the Prime Minister of Cameroon, Philemon Yang, signed a decree to officially create a new protected area – Tofala Wildlife Sanctuary – in the southwestern part of the country.

(10/28/2014) On March 1, 1872, the United States Congress declared 3,400 square miles of land spanning three states as the country’s – and the world’s – first national park. We call it Yellowstone. Today, there are over 160,000 PAs spanning 12.7 percent of the planet’s land surface.

Scientific association calls on Nicaragua to scrap its Gran Canal

(10/27/2014) ATBC—the world’s largest association of tropical biologists and conservationists—has advised Nicaragua to halt its ambitious plan to build a massive canal across the country. The ATBC warns that the Chinese-backed canal, also known as the Gran Canal, will have devastating impacts on Nicaragua’s water security, its forests and wildlife, and local people.

Conservationists propose Dracula Reserve in Ecuador

(10/24/2014) Deep in the dark, cool forests of Ecuador and Colombia live strange and mysterious organisms. Some inhabit the trees and others stay to the ground, and many are threatened by human encroachment. Because of this threat, Rainforest Trust has launched a Halloween fundraising drive to help pay for the creation of the Dracula Reserve–named for its dramatic inhabitant, the Dracula orchid.

Brazil declares new protected area larger than Delaware

(10/23/2014) Earlier this week, the Brazilian government announced the declaration of a new federal reserve deep in the Amazon rainforest. The protections conferred by the move will illegalize deforestation, reduce carbon emissions, and help safeguard the future of the area’s renowned wildlife.

- World Wildlife Fund. 2014. PADDDtracker.org Data Release Version 1.0 (January 2014). Washington, DC: World Wildlife Fund.