Andinobates cassidyhornae is a very recently described poison dart frog from the Western Andes of Colombia. It is typical of recently described species in having a very small geographical range and being in an area where habitat loss is a major threat to its existence. Photo by: Luis Mazariegos.

Current extinction rates are at the high end of past predictions, according to a new paper published today in Science, however conservation efforts combined with new technologies could make a big difference.

Past research has largely pinned current extinction rates at 100 to 1,000 times the background rate, which is the average rate of extinction as teased out from the fossil record. However, new research led by Stuart Pimm of Duke University argues that humans have pushed the current extinction rate to 1,000 times the historical rate.

“Humanity has driven rates of extinction even higher than we had previously thought,” co-lead author Clinton Jenkins with the Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas in Brazil explained to mongabay.com. “However, today we know better than ever which parts of the world are most important to protect for preventing future species extinctions, and new technologies are helping to monitor and learn about threats in those areas.”

The study finds that it’s not so much that more species are going extinct than feared, but that extinction likely occurred even slower in the past then previously predicted. Using three different types of evidence—the fossil record, speciation rates, and diversification across family groups—the researchers estimated that only 0.1 extinctions occurred in the past on average for every million species years (MSY), instead of the more commonly cited one extinction per MSY.

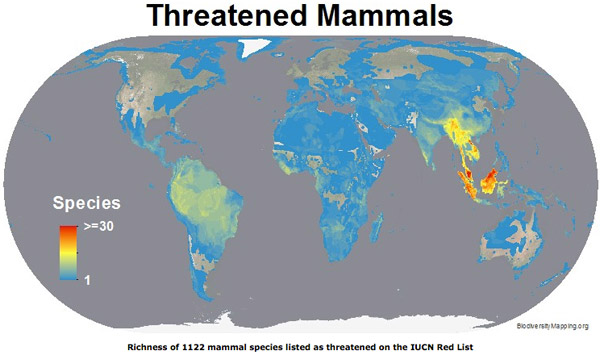

Map shows the regions with the most threatened mammals. Map courtesy of Biodiversitymapping.org.

This means that instead of one species going extinct each year for every million species on Earth, only one species went extinct for every TEN million species on the planet annually in the past. Today, the researchers believe that around 100 species are vanishing each year for every million species, or 1,000 times their newly calculated background rate.

“The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption,” states the paper. “How long these trends continue—where and at what rate—will dominate the scenarios of species extinction and challenge efforts to protect biodiversity.”

However, the scientists argue that ongoing conservation efforts and new technologies, including a massive increase in data, could stem global biodiversity loss.

“Online databases, smart phone apps, crowd sourcing and new hardware are making it easier to collect data on species. When combined with data on land-use change and the species observations from millions of amateur citizen scientists, they are increasingly allowing closer monitoring of the planet’s biodiversity and threats to it,” said Pimm. Notable online databases include Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the Ocean Biogeographic Information System, the Tree of Life, TimeTree, according to the paper. In addition, increasingly-popular tools such as conservation drones, genetic barcoding, photo sharing apps, and camera traps have made monitoring biodiversity much easier and cheaper.

“For our success to continue, however, we need to support the expansion of these technologies and develop even more powerful technologies for the future,” Pimm added.

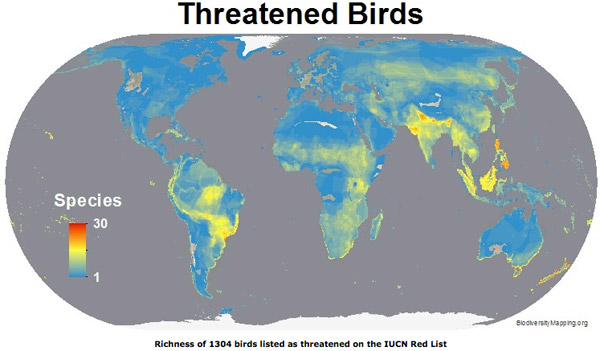

Map shows the regions with the most threatened birds. Map courtesy of Biodiversitymapping.org.

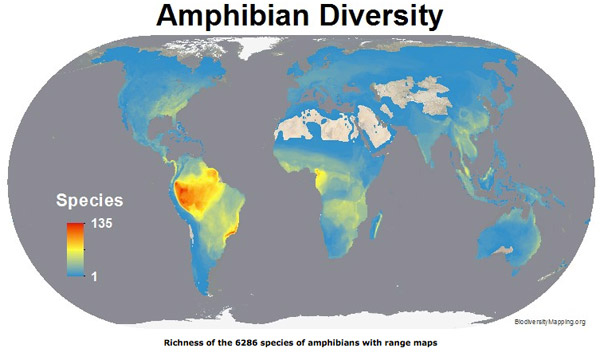

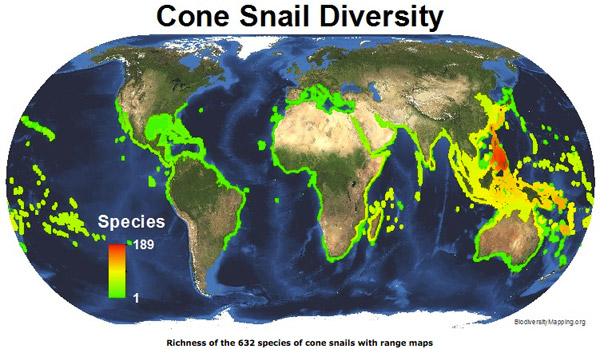

With this massive influx of new data, scientists have been able not only to identify the world’s most biodiverse places, but also where that biodiversity is most threatened. These include the tropical Andes, the Atlantic Forest, Madagascar, and the islands of Southeast Asia, according to Jenkins.

“We know what the major problems are. We know where they are. It is not a mystery,” said Jenkins. “I can walk out my door and see areas of Atlantic Forest being restored and the species returning. I know that it is possible, because I see people doing it every day where I work. What is needed globally is greater political will and resources devoted to solving the problem.”

Map shows the regions with the most amphibian species. Map courtesy of Biodiversitymapping.org.

Map shows the regions with the most cone snail species. Map courtesy of Biodiversitymapping.org.

Citations:

- Stuart L. Pimm, Clinton N. Jenkins, Robin Abell, Tom M. Brooks, John. L. Gittleman, Lucas N. Joppa, Peter. H. Raven, Callum. M. Roberts, and Joe O. Sexton. The Biodiversity of Species and Their Rates of Extinction, Distribution, and Protection. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.1246752

Related articles

Giant ibis, little dodo, and the kakapo: meet the 100 weirdest and most endangered birds

(04/10/2014) The comic dodo, the stately great auk, the passenger pigeon blotting out the skies: human kind has wiped out nearly 200 species of birds in the last five hundred years. Now, if we don’t act soon we’ll add many new ones to the list: birds such as the giant ibis, the plains-wanderer, and the crow honeyeater. And these are just a few of the species that appear today on the long-awaited EDGE list.

Mother of God: meet the 26 year old Indiana Jones of the Amazon, Paul Rosolie

(03/17/2014) Not yet 30, Paul Rosolie has already lived a life that most would only dare dream of—or have nightmares over, depending on one’s constitution. With the Western Amazon as his panorama, Rosolie has faced off jaguars, wrestled anacondas, explored a floating forest, mentored with indigenous people, been stricken by tropical disease, traveled with poachers, and hand-reared a baby anteater. It’s no wonder that at the ripe age of 26, Rosolie was already written a memoir: Mother of God.

Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record – book review

(03/04/2014) Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record reaches into your imagination and draws you closer to the final days of a variety of extinct animals on Earth. Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record is filled with poignant and powerful first-hand accounts, photographic records, and illustrations.

(02/20/2014) Due to the wonderful idiosyncrasies of evolution, there is one country on Earth that houses 20 percent of the world’s primates. More astounding still, every single one of these primates—an entire distinct family in fact—are found no-where else. The country is, of course, Madagascar and the primates in question are, of course, lemurs. But the far-flung island of Madagascar, once a safe haven for wild evolutionary experiments, has become an ecological nightmare. Overpopulation, deep poverty, political instability, slash-and-burn agriculture, illegal logging for lucrative woods, and a booming bushmeat trade has placed 94 percent of the world’s lemurs under threat of extinction, making this the most imperiled mammal group on the planet. But, in order to stem a rapid march toward extinction, conservationists today publicized an emergency three year plan to safeguard 30 important lemur forests in the journal Science.

Over 75 percent of large predators declining

(01/09/2014) The world’s top carnivores are in big trouble: this is the take-away message from a new review paper published today in Science. Looking at 31 large-bodied carnivore species (i.e those over 15 kilograms or 33 pounds), the researchers found that 77 percent are in decline and more than half have seen their historical ranges decline by over 50 percent. In fact, the major study comes just days after new research found that the genetically-unique West African lion is down to just 250 breeding adults.

Using stories to connect people to biodiversity: an interview with Tara Waters Lumpkin, PhD

(12/18/2013) In a world where extinctions are almost commonplace and global warming barely raises an eyebrow, very few of us can return to find the places we grew up in unsullied by development. Sometimes, all that is left of a favorite grove of trees or strip of forest are memories. Through Izilwane: Voices for Biodiversity Project, an online magazine for story-tellers, Tara Waters Lumpkin has succeeded in bringing together more than one hundred “eco-writers” who have shared their memories, highlighted environmental crises in their localities and raised their voices against habitat destruction.