Indonesian palm oil companies would support land swaps as a means to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation while simultaneously expanding production, representatives from the country’s largest association of palm oil producers told mongabay.com in an interview last month.

GAPKI General Secretary Joko Supriyono and Executive Director Fadhil Hasan said the Indonesian palm oil industry would support a mechanism under which palm oil companies could swap high carbon stock (HCS) and high conservation value (HCV) forest in so-called “APL” areas — lands zoned for conversion — for the equivalent area of non-forest lands that are part of the national “forest estate” if such exchanges were permitted by law. As much of 40 million hectares of Indonesia’s “forest estate” — land controlled by the powerful Ministry of Forestry — consists of land that is either stripped of forest or heavily degraded.

“GAPKI does not support the forestry moratorium because it makes APL land off-limits to oil palm expansion,” Joko told mongabay.com, referring to the current two-year ban on new plantation and logging concessions in some 14 million hectares of previously unprotected forest and peatland. “But GAPKI would agree to land swaps [where APL land with high carbon stock] is exchanged with degraded forest in the forest estate.”

Oil palm estate in Sumatra.

Under the current forestry law, degraded and non-forest land in the forest estate can’t be used for non-forestry uses unless the Ministry of Forestry relinquishes control of it. The GAPKI officials added that to meet government production targets of 40 million tons of crude palm oil by 2020, the Indonesian palm oil industry would need to both increase productivity of existing plantations Ô especially low-yielding smallholder lots — and expand the extent of plantations beyond the current 9 million hectares (34,700 square miles) in the country. Gapki’s 570 members control million hectares of that area.

Land swaps has been previously proposed by palm oil companies in Indonesia, but progress had been slow due to the complexities of competing and overlapping bureaucracies, unclear land title, and confusing regulations. The World Resources Institute (WRI), a U.S.-headquartered NGO, has tried to move the effort forward by mapping non-forest areas for potential expansion. It estimates that there may be some 50 million ha suitable for plantations without the need to clear carbon-dense forests.

New oil palm plantation on peatlands in Central Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo in March 2013. The palm oil paradox Palm oil is widely acknowledged as one of the most important drivers of deforestation and forest diminishment in Southeast Asia. Conversion of forests and peatlands for oil palm plantations is both a substantial source of greenhouse gas emissions and a major threat to biodiversity — one study called palm oil the “single most immediate threat to the greatest number of species”. Yet palm palm production generates tens of billions of dollars per year for the economies of Indonesia and Malaysia and is the most profitable form of land use across large swathes of Borneo, Sumatra, and New Guinea. Oil palm plantations also yield more edible oil than any other major crop, providing a cheap source of cooking oil for the poor. |

Palm oil companies and other developers often target forested lands because it can be easier to get a license than for degraded lands, which may have multiple competing claims, often from local communities. In some cases, timber felled during the clearing process can generate startup income to help offset the costs of establishing a plantation. But forest clearing leaves a company open to criticism from environmental groups, who note that forest and peat conversion is a huge source of greenhouse gas emissions and can threaten endangered wildlife like orangutans, elephants, and tigers, depending on the location.

Joko and Fadhil said they felt much of the criticism levied at the palm oil industry was unfair and failed to consider the context.

“Oils and fats demand is growing by 5-6 million tons per year globally and palm oil has the highest yield. Other crops take up more land to produce the same amount of oil,” said Joko, pointing to maize (corn) and rapeseed (canola).

In their view, conversion of forests outside the officially recognized forest estate shouldn’t count as deforestation because clearing is sanctioned by the government. In other words, it is legal, planned deforestation. Still, Joko and Fadhil admitted that there are some bad actors in the industry.

“The majority of palm oil plantations have already adopted palm oil sustainability schemes,” Fadhil asserted. “In some cases there is a violation but to generalize that all palm oil companies are bad and destroying [the environment] is baseless and wrong.”

When asked whether they thought Indonesian palm oil producers could suffer should Brazil successfully meet its ambitious expansion targets, Joko and Fadhil said they didn’t see the South American giant as a threat, citing the annual 5-6 million ton growth in vegetable oil demand. Brazil is aiming to convert up to 5 million hectares of degraded cattle pasture to oil palm plantations by 2020, which if achieved, would represent about 30 percent of current acreage worldwide.

Joko and Fadhil also downplayed the potential impact of the emergence of synthetic oils, like those derived from algae.

“Other oils have been popular at points in the past,” said Fadhil. “Palm oil’s advantage is it is highly productive, profitable [and] the supply chain is integrated from small farmers to big companies.”

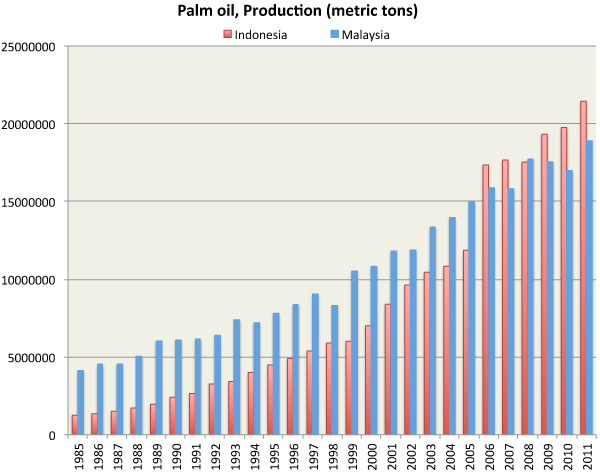

Malaysia and Indonesia are the largest palm oil producers in the world, accounting for 83 percent of global market share combined in 2011 according to the FAO.

Related articles

Cutting through the rhetoric on palm oil production

(12/14/2012) Palm oil is widely acknowledged as one of the most important drivers of deforestation and forest diminishment in Southeast Asia. Conversion of forests and peatlands for oil palm plantations is both a substantial source of greenhouse gas emissions and a major threat to biodiversity — one study called palm oil the ‘single most immediate threat to the greatest number of species’.

Palm oil giant making good on forest commitment in Indonesia, finds independent analysis

(05/29/2012) Palm oil giant PT SMART appears to be honoring its commitment to avoid conversion of high carbon forests in Indonesian Borneo, reports a new assessment published by Greenomics, an Indonesian environmental activist group. The report was issued 15 months after PT SMART — a subsidiary of Singapore-based Golden Agri Resources (GAR) and owned by Indonesia’s Sinarmas Group — signed a landmark agreement with The Forest Trust (TFT) to spare forests and peatlands that have more than 35 tons of carbon per hectare. The deal came after a damaging Greenpeace campaign, which targeted PT SMART for clearing orangutan habitat in Kalimantan and cost the company millions of dollars in contracts.

Surging demand for vegetable oil drives rainforest destruction

(03/14/2012) Surging demand for vegetable oil has emerged as an important driver of tropical deforestation over the past two decades and is threatening biodiversity, carbon stocks, and other ecosystem functions in some of the world’s most critical forest areas, warns a report published last week by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). But the report sees some reason for optimism, including emerging leadership from some producers, rising demand for “greener” products from buyers, new government policies to monitor deforestation and shift cropland expansion to non-forest area, and partnerships between civil society and key private sector players to improve the sustainability of vegetable oil production.

Carbon debt for some biofuels lasts centuries

(11/30/2011) It has long been known that biofuels release greenhouse gas emissions through land conversion like deforestation. But an innovative new study by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) published in Ecology and Society has computed how long it would take popular biofuel crops to payoff the “carbon debt” of land conversion. While there is no easy answer—it depends on the type of land converted and the productivity of the crop—the study did find that in general soy had the shortest carbon debt, though still decades-long, while palm oil grown on peatland had the longest on average.

Could palm oil help save the Amazon?

(06/14/2011) For years now, environmentalists have become accustomed to associating palm oil with large-scale destruction of rainforests across Malaysia and Indonesia. Campaigners have linked palm oil-containing products like Girl Scout cookies and soap products to smoldering peatlands and dead orangutans. Now with Brazil announcing plans to dramatically scale-up palm oil production in the Amazon, could the same fate befall Earth’s largest rainforest? With this potential there is a frenzy of activity in the Brazilian palm oil sector. Yet there is a conspicuous lack of hand wringing by environmentalists in the Amazon. The reason: done right, oil palm could emerge as a key component in the effort to save the Amazon rainforest. Responsible production there could even force changes in other parts of the world.

Breakthrough? Controversial palm oil company signs rainforest pact

(02/09/2011) One of the world’s highest profile and most controversial palm oil companies, Golden Agri-Resources Limited (GAR), has signed an agreement committing it to protect tropical forests and peatlands in Indonesia. The deal—signed with The Forest Trust, an environmental group that works with companies to improve their supply chains—could have significant ramifications for how palm oil is produced in the country, which is the world’s largest producer of palm oil.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Nestle’s palm oil debacle highlights current limitations of certification scheme

(03/26/2010) Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

Palm oil both a leading threat to orangutans and a key source of jobs in Sumatra

(09/24/2009) Of the world’s two species of orangutan, a great ape that shares 96 percent of man’s genetic makeup, the Sumatran orangutan is considerably more endangered than its cousin in Borneo. Today there are believed to be fewer than 7,000 Sumatran orangutans in the wild, a consequence of the wildlife trade, hunting, and accelerating destruction of their native forest habitat by loggers, small-scale farmers, and agribusiness. Gunung Leuser National Park in North Sumatra is one of the last strongholds for the species, serving as a refuge among paper pulp concessions and rubber and oil palm plantations. While orangutans are relatively well protected in areas around tourist centers, they are affected by poorly regulated interactions with tourists, which have increased the risk of disease and resulted in high mortality rates among infants near tourist centers like Bukit Lawang. Further, orangutans that range outside the park or live in remote areas or on its margins face conflicts with developers, including loggers, who may or may not know about the existence of the park, and plantation workers, who may kill any orangutans they encounter in the fields. Working to improve the fate of orangutans that find their way into plantations and unprotected community areas is the Orangutan Information Center (OIC), a local NGO that collaborates with the Sumatran Orangutan Society (SOS).