The accidental introduction of the brown tree snake on Guam has resulted in a loss of birds and a subsequent explosion of spiders. Photo by: Isaac Chellman.

The island of Guam is drowning in spiders. New research in the open-access journal PLOS ONE has found that in the wet season, Guam’s arachnid population booms to around 40 times higher than adjacent islands. Scientists say this is because Guam, a U.S. territory in the Pacific, has lost its insect-eating forest birds. Guam’s forests were once rich in birdlife until the invasion of non-native brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis) in the 1940s decimated biodiverse bird communities. Now, the island is not only overrun with snakes, but spiders too.

“You can’t walk through the jungles on Guam without a stick in your hand to knock down the spiderwebs,” says lead author Haldre Rogers, a Huxley Fellow in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Rice University.

Rogers and her team counted spider webs in order to estimate spider abundance on the island. In the wet season, the team averaged 18.37 spider webs every 10 meters (around 33 feet), and in the dry season spiders were even more abundant: 26.19 webs for every 10 meters. Since there was no historical data of spider abundance prior to the loss of bird communities, the researchers compared Guam’s spider abundance to similar nearby islands with intact bird communities: Rota, Tinian, and Saipan. In the dry season, Guam’s spider abundance was more than twice as large as its neighbors, but it was the wet season when things got really wild: spider abundance on Guam exploded to 40 times the number on other islands.

Guam’s unique subspecies of Micronesian kingfisher has been eradicated from the island by the brown tree snake, however zoos are currently breeding the bird and hope to return it to the island one day. Photo by: Dylan Kesler. |

The study proves that “birds have a strong effect on spiders,” Rogers says. “Anytime you have a reduction in insectivorous birds, the system will probably respond with an increase in spiders.”

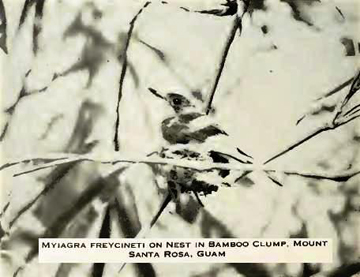

Brown tree snakes, which are native to Australia and Papua New Guinea, have been an ecological disaster for Guam, but to date no one has determined a method to rid the island of the rarely-seen, nocturnal snakes. In 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ‘bombed’ the island with dead, frozen mice laced with acetaminophen to poison the snakes, and the country already spends over a $1 million very year working to make sure the brown tree snake doesn’t make it off the island to invade somewhere else. The snake population is believed to be currently in decline due to exceeding its overall carrying capacity, but its too late for most of Guam’s birds. Nine birds have become locally extinct in Guam with five of these (either species or subspecies) found no-where else, including the Guam flycatcher (Myiagra freycineti) which was last seen in 1983.

“Birds pollinate our crops, control crop pests, and, it would seem, keep spider populations from exploding,” George Fenwick, President of American Bird Conservancy, said in a press statement.

“Arachnophobes and those afraid of snakes would do well to stay out of the forests of Guam,” he added. But the problem may go beyond Guam according to Rogers.

“With insectivorous birds in decline in many places in the world, I suspect there has been a concurrent increase in spiders,” she says.

Currently, Guam provides a natural laboratory whereby one can see just how the loss of one group of species impacts others.

Photo of the now extinct Guam flycatcher. Photo by: Smithsonian. |

“There isn’t any other place in the world that has lost all of its insect-eating birds,” Rogers said. “There’s no other place you can look to see what happens when birds are removed over an entire landscape.”

While Rogers had her teams suspect that spiders are more abundant on Guam due directly to a lack of predation from birds, they also write that bird loss may have other impacts that benefit spiders. For example, spiders no longer have to compete with insect-eating birds for prey and may expend less energy on re-building webs destroyed by flying birds.

For now Rogers says snakes and spiders won’t keep her away from continuing to explore Guam’s bizarre environment, including a rainforest almost wholly empty of birdsong.

“Ultimately, we aim to untangle the impact of bird loss on the entire food web, all the way down to plants,” she says. “For example, has the loss of birds also led to an increase in the number of plant-eating insects? Or can this increase in spiders compensate for the loss of birds?”

Spider bonanza in Guam. Photo by: Isaac Chellman.

CITATION: Rogers H, Hille Ris Lambers J, Miller R, Tewksbury JJ (2012) ‘Natural experiment’ Demonstrates Top-Down Control of Spiders by Birds on a Landscape Level. PLoS ONE 7(9): e43446. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043446

Related articles

Forgotten species: the plummeting cycad

(12/06/2010) I have a declarative statement to make: cycads are mind-blowing. You may ask, what is a cycad? And your questions wouldn’t be a silly one. I doubt Animal Planet will ever replace its Shark Week with Cycad Week (perhaps the fact that it’s ‘animal’ planet and not ‘plant’ planet gave that away); nor do I expect school children to run to see a cycad first thing when they arrive at the zoo, rushing past the polar bear and the chimpanzee; nor do I await a new children’s book about a lonely little anthropomorphized cycad just looking for a friend. In the world of species-popularity, the cycad ranks pretty low. For one thing, it’s a plant. For another thing, it doesn’t produce lovely flowers. And for a final fact, it looks so much like a palm tree that most people probably wouldn’t know it wasn’t. Still, I declare the cycad to be mind-blowing.

Massive snake found in Florida (photos)

(08/14/2012) Researchers in Florida have documented the biggest snake ever found in Florida. But the snake is an invader — it’s not native.

Meet the world’s rarest snake: only 18 left

-(Large).150.jpg)

(07/10/2012) It’s slithery, brown, and doesn’t mind being picked up: meet the Saint Lucia racer (Liophis ornatus), which holds the dubious honor of being the world’s most endangered snake. A five month extensive survey found just 18 animals on a small islet off of the Caribbean Island of Saint Lucia. The snake had once been abundant on Saint Lucia, as well, but was decimated by invasive mongooses. For nearly 40 years the snake was thought to be extinct until in 1973 a single snake was found on the Maria Major Island, a 12-hectare (30 acre) protected islet, a mile off the coast of Saint Lucia (see map below).

Island bat goes extinct after Australian officials hesitate

(05/23/2012) Nights on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean will never again be the same. The last echolocation call of a tiny bat native to the island, the Christmas Island pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), was recorded on August 26th 2009, and since then there has been only silence. Perhaps even more alarming is that nothing was done to save the species. According to a new paper in Conservation Letters the bat was lost to extinction while Australian government officials equivocated and delayed action even though they were warned repeatedly that the situation was dire. The Christmas Island pipistrelle is the first mammal to be confirmed extinct in Australia in 50 years.

Invasion!: Burmese pythons decimate mammals in the Everglades

(01/30/2012) The Everglades in southern Florida has faced myriad environmental impacts from draining for sprawl to the construction of canals, but even as the U.S. government moves slowly on an ambitious plan to restore the massive wetlands a new threat is growing: big snakes from Southeast Asia. A new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) has found evidence of a massive collapse in the native mammal population following the invasion of Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivittatus) in the ecosystem. The research comes just after the U.S. federal government has announced an importation ban on the Burmese python and three other big snakes in an effort to safeguard wildlife in the Everglades. However, the PNAS study finds that a lot of damage has already been done.

California city bans bullfrogs to safeguard native species

(01/26/2012) Santa Cruz, California has become the first city in the U.S. to ban the importation, sale, release, and possession of the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). Found throughout Eastern and Central U.S., the frogs have become an invasive threat to wildlife in the western U.S. states and Canada.

U.S. implements snake ban to save native ecosystems

(01/25/2012) Last week the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced it was banning the importation and sale across state lines of four large, non-native snakes: the Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus), the yellow anaconda (Eunectes notaeus), and two subspecies of the African python (Python sebae). Although popular pets, snakes released and escaped into the wild have caused considerable environmental damage especially in the Florida Everglades.