Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions reached 2.1 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2005, making it the world’s third largest emitter of greenhouse gases, but offering opportunities to substantially reduce emissions through forest conservation, reduced use of fire, protection of peatlands, and better forest management, reports a series of studies released earlier this month by the country’s National Climate Change Council (DNPI).

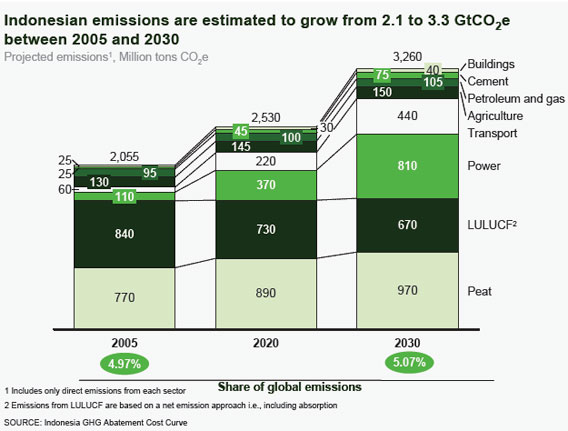

The research—which analyzed current greenhouse gas emissions emissions and reduction potential in eight sectors: peat, forestry, agriculture, power, transportation, petroleum and gas, cement and buildings—found that 85 percent of the country’s emissions result from land use: 41 percent come from degradation and destruction of peatlands, while 37 percent result from deforestation (currently 800,000 hectares per year), degradation through logging (1 million hectares), and forest fires. It estimated that Indonesia’s emissions would reach 2.5 billion tons of CO2 by 2020 and 3.3 billion tons by 2030 under current growth rates.

GHG Abatement Curve for Indonesia |

But using a greenhouse gas abatement curve developed by McKinsey & Co, the research identified a number of options for significantly cutting projected emissions at low cost. The five biggest opportunities were preventing deforestation (570 million metric tons in 2030), preventing peatland fires (310 m tons), managing and restoring peatlands (250 m tons), implementing and enforcing sustainable forest management (SFM) (240 m tons), and reforesting marginal and degraded forests (150 m tons). In total, the analysis concluded that better land management could cut emissions by 1.9 billion tons by 2030, or more than the current industrial emissions of India.

The research indicates that cutting emissions will contribute to Indonesia’s long-term economic growth relative to conventional approaches, chiefly because “many emissions sources are not economically productive.” For example, peat fires cost the country up to $4 billion annually due to “material losses, delayed logistics and health problems,” according to a statement released with the reports.

“Indonesia’s GHG emission profile is unique because it is heavily dominated by emissions

from forest and peatland where more efficient use of the land both increases economic value

and reduces GHG emissions,” reads the statement. “Stopping the use of fire as a tool for land clearing, improving

logging practices so less timber is left to rot and goes to waste, reforestation of areas

degraded by unsustainable logging practices, rehabilitation of previously opened peatlands

are some examples of high-impact GHG mitigation initiatives in the green growth strategies.

They share the principle that their long-term economic value greatly outweighs the benefits

from continuing current unsustainable and high GHG emitting activities.”

Logged peatland in Borneo |

The researchers cite East Kalimantan as an example. The province, located on the eastern part of Indonesian Borneo, is experiencing large-scale forest and peatland conversion for timber production and plantations. But the study finds the province can boost its GDP growth from a business-as-usual rate of 3 percent year per year to

5 percent “without increasing emissions by moving to higher value-added activities and

promoting less carbon-intensive sectors.”

“In a developing economy like Indonesia the people will not choose to reduce GHG

emissions if to do so mean slowing economic growth. Our strategy does not require that

choice,” said Rachmat Witoelar, Executive Chair of the

DNPI. “We have found that economic development and GHG mitigation can be mutually

reinforcing. A more sustainable economic path requires a paradigm shift, but in the long-term

it will increase Indonesia’s economic growth.”

Reports from Indonesia’s National Climate Change Council (DNPI)

- Indonesia GHG Cost Curve – English PDF-6.1 MB

- Central Kalimantan Report – low carbon growth strategy PDF-93.8 MB [cached]

- East Kalimantan Report – low carbon growth strategy PDF-32.9 MB [cached]

- Jambi Report – low carbon growth strategy PDF-15.5 MB [cached]

- DNPI Press Conference Fact Sheet – English PDF-81 KB

Related articles

Indonesia implements export ban on non-certified timber

(09/15/2010) Indonesia has begun implementing a ban on exports of illegally harvested timber and wood products, reports The Jakarta Post.

How best to balance economic growth and protection of the environment?

(08/30/2010) When people are hungry for an uncertain income, they will destroy everything. When people become poor due to a poor decision they were excluded from making, who should be responsible for that? Development is seen as the answer to poverty. However, many controversial developments have actually increased poverty, and while the investors in such schemes may benefit, the local people pay the price. This happened in Tundai, a fishing village in the ex-mega rice area near Palangkaraya, Central Kalimantan. When central government in the 1990s decided to convert the peat swamp forests into rice fields, the community had no voice or involvement in the decision. The project failed. Now over a million hectares of former lush forests have become a wasteland, and the people of Tundai have been thrust into poverty.

(07/29/2010) Many of the environmental issues facing Indonesia are embodied in the plight of the orangutan, the red ape that inhabits the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Orangutan populations have plummeted over the past century, a result of hunting, habitat loss, the pet trade, and human-ape conflict. Accordingly, governments, charities, and concerned individuals have ploughed tens of millions of dollars into orangutan conservation, but have little to show in terms of slowing or reversing the decline. The same can be said about forest conservation in Indonesia: while massive amounts of money have been put toward protecting and sustainable using forests, the sum is dwarfed by the returns from converting forests into timber, rice, paper, and palm oil. So orangutans—and forests—continue to lose out to economic development, at least as conventionally pursued. Poor governance means that even when well-intentioned measures are in place, they are often undermined by corruption, apathy, or poorly-designed policies. So is there a future for Indonesia’s red apes and their forest home? Erik Meijaard, an ecologist who has worked in Indonesia since 1993 and is considered a world authority on orangutan populations, is cautiously optimistic, although he sees no ‘silver bullet’ solutions.

(07/23/2010) Scientists convening at the annual Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) meeting in Sanur, Bali urged Indonesia’s leaders to strengthen measures to protect the country’s biologically-rich ecosystems. In a resolution issued on the final day of the five-day conference, ATBC commended Indonesia for recent moves to protect forests, including a pledge to cut illegal logging and a billion dollar partnership with Norway to reduce deforestation and forest degradation, but asked the government to immediately implement a planned moratorium on new forestry concessions on peatlands and primary forest lands.

Indonesia’s plan to save its rainforests

(06/14/2010) Late last year Indonesia made global headlines with a bold pledge to reduce deforestation, which claimed nearly 28 million hectares (108,000 square miles) of forest between 1990 and 2005 and is the source of about 80 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said Indonesia would voluntarily cut emissions 26 percent — and up to 41 percent with sufficient international support — from a projected baseline by 2020. Last month, Indonesia began to finally detail its plan, which includes a two-year moratorium on new forestry concession on rainforest lands and peat swamps and will be supported over the next five years by a one billion dollar contribution by Norway, under the Scandinavian nation’s International Climate and Forests Initiative. In an interview with mongabay.com, Agus Purnomo and Yani Saloh of Indonesia’s National Climate Change Council to the President discussed the new forest program and Norway’s billion dollar commitment.